Written by: Dr. Dushka H. Saiyid

Posted on: September 11, 2020 |

A view of Quaid-i-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah

The Quaid had parted ways with the Congress when the mantle of its leadership passed from secular constitutionalists of the likes of Naoroji, Pherozeshah Mehta and Gokhale to Gandhi. The latter’s populist non-cooperation methods with religious undertones, left the Quaid in fear of the emergence of a Hindu majoritarian state.

This period is marked by the Quaid’s attempts to get the Congress to agree to safeguards for the Muslim community of 70 million; transform the Muslim League into a mass party; get the leadership of the Muslim majority provinces of Bengal, Punjab and Sindh to join his struggle to get a fair deal for the Muslims of India. His struggle was on three fronts: British, Congress and the parochial provincialism of Muslims.

When the Muslim League met in Old Delhi in March 1929, it was a house divided: Mian Shafi headed his own Muslim League in Punjab, Sir Agha Khan his All-India Muslim Conference and a Muslim Nationalist Party in the United Provinces, headed by Khaliquzzaman and Dr. Ansari. A melee had broken out on one of the days, and the meeting had been adjourned, a poor reflection on the state of the party.

When that summer the Tory government fell, and Ramsay Macdonald of the Labour Party became the new Prime Minister, it was the Quaid who persuaded Viceroy Irwin to get the new government to call a Round Table Conference (RTC) and to make a declaration in favor of a responsible government with Dominion Status to be their goal for India.

The Quaid-e-Azam Muhammad Ali Jinnah seated next to Allama Iqbal during the first Round Table Conference, 1930

At the first RTC, held between November 1930 and March 1931, the Quaid declared for the first time that there were four parties in India: the British, Congress, Princes and the Muslims. At the RTC there was a deadlock between the Muslims and the Hindu delegation led by Moonje. The latter had agreed on Quaid’s fourteen points earlier on, but now went back on it. The fourteen points had various clauses, which offered protection to Muslim interests (Muslim representation in the centre of not less than one-third, separate electorates, no bill to be passed without support from three-fourths of members of the community who might consider it opposed to their community’s interests, Sindh to be separated from the Bombay Presidency, reforms to be introduced in the North-West Frontier Province and Baluchistan as in other provinces and more).

The Quaid had asked Allama Iqbal to preside over the Muslim League’s annual session at Allahabad on 29 December 1930. While the RTC made no progress, Iqbal unfurled the flag of the two-nation theory in his now-famous presidential address. He said that the concept of European democracy could not be applied to India because of the different communities inhabiting it. Then he outlined his vision for Muslims: “I would like to see the Punjab, the North-West Frontier Province, Sind and Baluchistan amalgamated into a single State. Self-government within the British Empire, or without the British Empire, the formation of a consolidated North-West Indian Muslim State appears to me to be the final destiny of the Muslims, at least of North-West India.”

The political temperature was being raised by the Congress, as Gandhi launched his 24-day Dandi march against the salt tax on 12th March, 1930, and at its session in Lahore in December, the Congress declared Purna Swaraj or complete independence to be its goal rather than Dominion Status.

A positive outcome of the second RTC, held from September to December 1931, for Muslims was that the Frontier was given a governor status, and Sindh made into a full province. Both demands were listed in Quaid’s fourteen points. The third RTC ended in December 1932, with the announcement that Muslims would be given one-third representation at the federal centre, while Orissa and Sind would become the new provinces of British India.

The British government in August 1932 made the Communal Award. It gave Muslims 51% of the seats in the Punjab Assembly, just under 50% in Bengal, and separate electorates and Muslim representation in excess of total population proportions in all Hindu majority provinces. A White Paper was presented by the government on Indian constitutional reforms that the Tories opposed, as did the Quaid. He was hoping that if the Congress accepted the communal award then the Muslim League and the Congress could jointly oppose the White Paper. He was hoping to wean the Congress away from dependence on the Mahasabha. In a statement to the Associated Press, he declared, “… The crux of the whole issue therefore is: can we completely assure Muslims that the safeguards to which they attach vital importance will be embodied in the future Constitution of India?”

However, the concerns of Muslims of India about their future, found expression in Chaudhry Rehmat Ali’s pamphlet demanding the creation of Pakistan published in 1933. However, unlike Iqbal at Allahabad, this Cambridge student wanted a separate federation for the provinces of Punjab, Frontier, Kashmir, Sindh and Baluchistan.

The Quaid spent 1938-39 building up a mass party, and the membership of the Muslim League increased from a few thousand to half a million by March 1940. At the Bombay session of the ML in April 1936, the Quaid began the process of transforming the ML into a mass party. The Quaid spoke against the 1935 Act but advocated constitutional agitation, declaring a revolution impossible and the non-cooperation movement a failure.

The Quaid went to Bengal in August of 1936 where the Muslims were divided between the Nawab of Dacca’s United Muslim Party and Fazlul Haq’s Krishak Proja Samiti (Peasants and Tenants Party). While the Nawab of Dacca agreed to merge his party with the Muslim League, Fazlul Haq initially promised to do so, but then reneged. With the United Muslim Party came such luminaries as Khwaja Nazimuddin and Suhrawardy, both of whom later served as the Prime Ministers of Pakistan.

Provincial elections were held in 1937, under the Act of 1935, and the final results were out in February. The ML got 109 seats, while Congress won 716 seats out of 1585 seats. While the Congress had emerged victorious in eight provinces, the Muslim League failed to form government in any province. However, the success of the Congress hid their dismal failure to win over Muslims to their side. There were 482 Muslim seats, the Congress put up candidates on 58 of these, and won only 26 seats. Having met with success in the elections, Nehru declared that there are only two forces in the country, the Congress and the government. Jinnah countered that no, there is a third force, Muslims. Maulana Azad was the only Muslim on the Working Committee of the Congress, and he also managed to wean away Ullama-e-Hind from the Muslim League

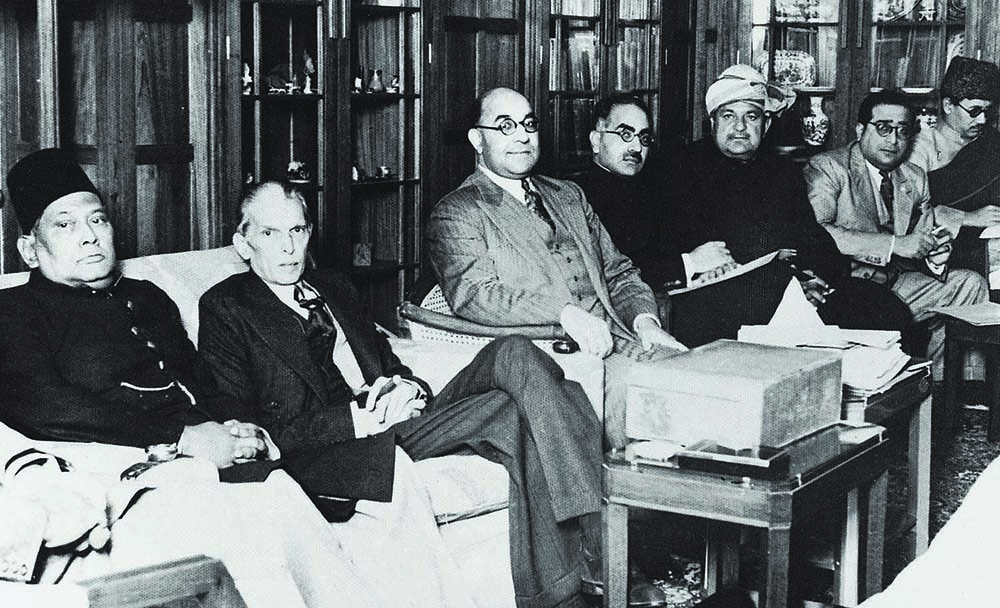

A Council Meeting in Bombay in the 1940's. (L to R) A.K. Fazlul Haq, Muhammad Ali Jinnah, Liaquat Ali Khan, Sir Sikander Hayat Khan, Sardar Aurangzeb Khan, and Amir Ahmed Khan(photo credits to Dawn)

The Muslim League session at Lucknow in October 1937 proved to be a turning point for the League. The election results seem to have had the desired effect on the Muslim provincial leadership. Sikander Hayat agreed to join the party but while retaining his party’s autonomous status in the Punjab. Problem was that the Muslim League had only won 2 seats out of 86 Muslim members in the Punjab. Fazlul Haq also came on board the party. At Lucknow, the Party resolved to build a federation of free democratic states, where the rights of the minorities, especially Muslims, would be protected. It was the first time that the Quaid emerged dressed in sherwani and a karakuli cap, which became the hallmark of his appearance from this time onwards.

The Quaid had been an indefatigable advocate of Sindh being made into a separate province, and his efforts had born fruit after the second RTC. The Quaid had been invited to Karachi in October 1938. Flanked by Sikander and Fazlul Haq, he held meetings with the Allah Bux Soomro, the Premier of a multi-factional coalition in the Sindh Assembly. Allah Bux agreed to join the Muslim League with his group, but when they met the next day, he reneged on the agreement on Sardar Patel’s behest.

Later that month, at the annual session of the Muslim League at Patna in December 1938, Jinnah was acclaimed as Quaid-i-Azam or the Great Leader. The Patna annual session was important for a number of reasons: it passed the resolution authorizing the Working Committee of the League to resort to “direct action”, a departure from its past practice of only using constitutional means to further its goals; it created a Muslim women’s sub-committee headed by Fatima Jinnah, despite resistance from the more conservative sections of the party. It was at Patna that the Quaid attacked Gandhi directly: “I have no hesitation in saying that it is Mr. Gandhi who is destroying the ideal with which the Congress was started. He is the one man responsible for turning the Congress into an instrument for the revival of Hinduism. His ideal is to revive the Hindu religion and establish Hindu Raj in the country, and he is utilizing the Congress to further this object …”

The Quaid had appointed three different committees to look into the excesses against Muslims in the Congress run provinces: the Pirpur Committee in November ’38, Fazlul Haq’s committee in 1939, and the Bihar Muslim League, which only examined their excesses in Bihar.

When after the German invasion of Poland, Linlithgow met Gandhi and then Jinnah on the 4th of September. The latter assured him of Muslim support but asked for something to take back to Muslims. He was asked whether the Congress ministries should be dissolved, and not surprisingly, the Quaid readily agreed, saying, “nothing else will bring them to their senses”. It is at this meeting that the Quaid conveyed to the Viceroy for the first time that he saw Partition as the only solution to the communal problem.

The Congress refused to support the British in the war against the Axis powers, saying it was only to defend the status quo. Jinnah on the other hand supported the government. On 2nd December the Quaid announced that the Muslim League would celebrate Friday 22nd December as the Day of Deliverance from the Congress rule. The Quaid got support on this from Ambedkar, the Justice Party of South India and smaller Anglo-Indian groups.

By now the Quaid’s health was failing. He met the Viceroy on March 13, and assured him that Muslims would not retard the war effort if they were given an undertaking that no settlement with the Congress would be made without the consent of the Muslims. The Viceroy reacted favorably and promised to communicate this to London. A big public meeting was planned for the 22nd of March 1940 in Lahore, but on March 19, there was a clash of the Khaksars with the police and a curfew was imposed in the city. Jinnah insisted on going through with the planned meeting despite the misgivings of the Punjab Prime Minister Sikander Hayat.

More than 60,000/ were gathered at the Minto Park in Lahore. The Quaid entered the venue of the meeting at 2:25 pm in his sherwani and his karakuli cap. The Quaid started speaking in Urdu, and then switched to English, saying that the world is watching us. There were some murmurs of dissatisfaction, and then they listened to him quietly, and he spoke for two hours uninterrupted. Thanks to the Associated Press International, Reuters and UPI, Jinnah’s message was read all over the world, especially in the corridors of power in London. Addressing Gandhi, the Quaid said, “why not come as a Hindu leader proudly representing your people, and let me meet you proudly representing the Musalmans? That is all that I have to say while the Congress is concerned.” The Quaid thundered, “the Musalmans are not a minority. The Musalmans are a nation by any definition. …the only course open to us all is to allow the major nations separate homelands, by dividing India into “autonomous national States.” By the spring of 1940, Jinnah had decided that partition was the only solution to India’s most important problem. The Ambassador of Hindu-Muslim unity had transformed himself into Pakistan’s great leader. This address lowered the curtain on a united India.

You may also like: