Written by: Eeman Amjad

Posted on: October 22, 2013 |  | 中文

| 中文

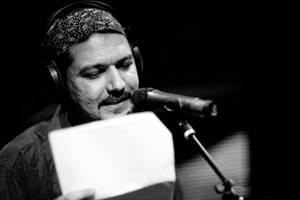

A child of a left wing political struggle, a disillusioned socialist, a street singer from Zagreb, the voice of Husn-e-Haqiqi on Coke Studio, and a sort of troubadour of the human soul; the man in a light blue shirt, curly hair and a cigarette in one hand talks casually of all these stages that unfolded to make him Arieb Azhar.

Arieb stepped into the spotlight when he received a call from Rohail Hayat, the architect of Coke Studio. He had heard some of Arieb’s music and wanted to hear more. “It was a delight to be part of Coke Studio,” Arieb related, impressed with the level of professionalism and respect that the musicians met. “Every artist feels welcomed.” That is the reason, he believed, for Coke Studio’s success. “They saw the value of real, genuine music, brought that into a more glamorized context and, in doing so, brought diverse music to the attention of a wider urban audience.”

But he also says, “Today there is scope for new projects to come out since it’s not good for the industry to be monopolized by one single project. One example of a beautiful project is ‘The Lahooti Sessions’, which is showcasing the genuine folk music of Sindh. I hope they are never short of money!”

But years before the fame of Coke Studio, Arieb was a young socialist whose music was occupied with socialist anthems, the poetry of Faiz and the working class movement. His early years were spent in a background of folk tunes and the classical voices of Shaukat Ali, Tufail Niazi and Alam Lohar, as his father Aslam Azhar was establishing PTV. When Aslam Azhar was displaced during the Zia-ul-Haq era, his family moved to Karachi. Although, the sets of Pakistan’s first television channel were his temporary home, they left the imprints of a deep-rooted love for the inherited culture of his home country.

|

The young socialist traveled to Moscow when he was only seventeen, to study and live on the ideals of communism in what he thought would be an equal and classless society, but was instead met with only disillusionment. The Soviet Union, plagued with corruption and despair, was only a hollow bubble of the communist vision. Most people still had hope for humanity and change, but their state had failed them. Arieb lost all conviction in any “ism”. The only truth and ideology to struggle for would be “humanity”. In Pakistan he had already made friends with a filmmaking couple from Yugoslavia, who convinced him to come to their country that offered the best of capitalism and socialism.

The year was 1990, and a year later, the ethnic puzzle of Yugoslavia would disintegrate into a brutal civil war. In the midst of the deadliest war in Europe since World War II, Arieb picked up his guitar and, like the teenager who played on the streets in the socialist movement in Karachi, Arieb played, not for any “ism”, but for the hope of humanity. He was just a man on the streets, playing at pubs and restaurants with different combinations and musicians. Later, he formed a band called ‘The Shamrock Rovers’, an eclectic mix of an Irishman, a Pakistani and Croats playing a fusion of Celtic and Irish music. The Shamrock Rovers performed for seven years playing around the pub circuit of Central and Eastern Europe. Arieb fell in love with the euphoria, the beauty and the people. He stayed on in Croatia, which eventually became his adopted home for thirteen years.

|

Arieb had initially moved to study philosophy and Indology, which gave him a chance to study the ancient culture of the land to which he belonged. He immersed himself in the study of Sanskrit and the philosophical teachings of the Vedas, and Buddhist and Sikh scripture, but eventually the music pulled him away from completing his degree. He admits that his short time in academia gave him a sense of his own history. But Arieb never really abandoned his degree, as philosophy and spirituality in the ancient texts would eventually always find a way into the soul of his music.

In the thirteen years in Eastern Europe, Arieb played all sorts of music, from Gypsy to South American to Irish music. Eventually, he became more interested “in our music and decided to come back and delve into it”. He felt that “I had lost touch with the soul element of music and stopped growing as an artist”. His upbringing in the background of folk culture and music revisited him; as he excavated into the lost poetry and folk tunes of Pakistan, his music attention drifted towards the humanist aspect of the Sufi kalams. His first album, Wajj, released in 2006, comprised of eight tracks, in which he vocalized the classical lyrics of Khawaja Ghulam Farid, Bulleh Shah, Mian Muhammad Baksh, and even the contemporary lyrics of Sarmad Sehbai. However, he rejects the Sufi box that he has been trapped into. “I have gotten categorized as Sufi musician for the new generation- the youth.” Perhaps an easier way to de-mystify the global musician, “but I never claimed to be a Sufi musician; Sufism is something every person understands individually.” To him the “ism’ is not important; Sufi poetry is about always discovering and never quite saying I have arrived. For him, the philosophy of Sufi poetry “is beyond religion, or maybe it is connected to the true Religion of all Humanity.”

To Arieb, the music and the philosophy need to be in harmony, but in a country with a fledgling music industry, musicians need to understand their own culture and roots better in order to build upon it. About his own band he says, “I would want that we create much more of our own music, and that this music reach out to a wider audience, particularly a greater street audience.” Arieb’s own music stems from not only the poetry he reads, the places he travels, and the instruments he hears, but from an understanding of the value of the human soul. The man in the blue shirt puts out half his remaining cigarette. “One always struggles,” he contemplates. “I struggled to live as an artist. A time came when hard work started paying off. It’s never easy.” It is his struggle as an artist to harmonize the eternal ballads of poetic wisdom and to create a blend of ethno-music that doesn’t fit into any box or genre. Maybe that is why people have a hard time defining Arieb Azhar: a troubadour of the human soul.

You may also like: