Written by: Dr. Dushka H. Saiyid

Posted on: April 07, 2015 |

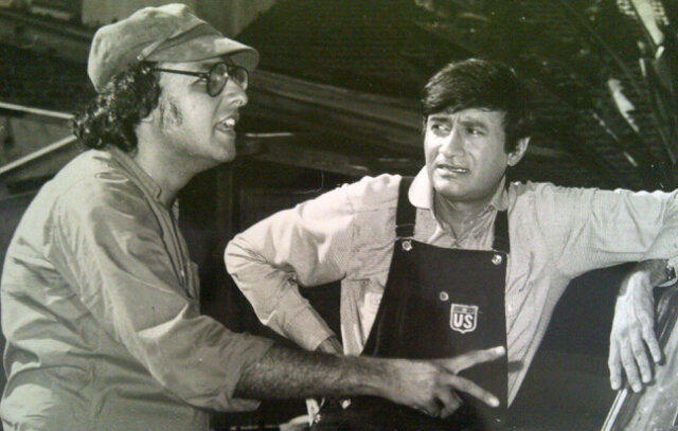

Mahesh and Pooja Bhatt

Hameed mentions that it was the Kara Film Festival that first brought Mahesh Bhatt to Pakistan and opened the door to Indian films, and only three years later in 2006, the unthinkable became possible, when his film Jannat premiered simultaneously in Lahore and Mumbai. As an example of the groundswell in favour of Pakistani actors and serials, Mahesh mentions that the Indian channel Zindagi (Z), only shows Pakistani soaps, and Fawad Khan is the first Pakistani actor to win a Filmfare Award. While he sees stirrings of new life in Pakistani cinema that began with Shoaib Mansoor’s Khuda Kay Liye and Bol, it is the Pakistani musicians that he holds in high regard, and says that they have helped revive the Indian music scene. While he was in Karachi, he met Atif Aslam and Amir Jamal, who wrote and composed Kaho Na Kaho for him, while Pooja Bhatt brought Rahat Fateh Ali and Ali Azmat’s music to Indian cinema.

I broach the topic of his love for the Urdu language, and he begins to talk about his mother, her memory flowing out like molten lava, intense and consuming. The first word he learnt was his mother’s name Shireen, which means sweet in Urdu. She was beautiful, “a small time actor”, who fell in love with a director and producer of Hindi and Gujrati films in Bombay. She bore him five children, but Nanabhai Bhatt, a Nagar Brahmin, did not marry Shireen Mohammed Ali because of community pressure. I watch the largely autobiographical film Zakhm, in which ironically enough, Pooja plays the role of the mother. Shireen became a “closet Muslim”, brought up her children as practicing Hindus, while Nanabhai Bhatt married into his caste and raised another family.

Mahesh recalls how his mother would undergo a transformation and come to life when they would go from Sivaji Park, to visit her sister Poornima in Pali Hill, an affluent suburb of Bombay. Poornima was a successful actor, and was proud of her Muslim identity and culture. Mahesh nostalgically recalls the aroma of biryani and the taste of siwayan and sheer khorma (dishes common to Muslims of India and Pakistan) over Eid. The return home was not joyful, where his mother would be “posturing” as a Hindu woman, while offering her prayers in secret, much to the chagrin of the child Mahesh.

One of Shireen’s last wishes to Mahesh, her elder son, was for a Muslim burial. He fulfilled her wish, but not without resistance from the rest of the family, who, like Shireen, felt secure in conforming to their Hindu identity. Nanabhai Bhatt came to see her as she was being given her last rites, put sindoor on her forehead, a sign that a woman is married, and tulsi in her mouth, thus claiming her as his wife in death. He refused to go to the graveyard, but later regretted it and asked to go to the grave with recorded verses of the Holy Quran. Pooja adds that when her grandmother died, they found hundreds of cassettes with Nanabhai’s messages of love and poetry hidden under her mattress, because by then he had gone blind and could not write to her.

Nanabhai Bhatt had told his wife that while he had lived with her in his lifetime, he wanted to be with Shireen in death. Consequently, when he died in hospital, on his wife’s instruction, his body was taken to Shireen’s house, and from there for cremation. The tragic love story reached its climax, when some of the close relatives climbed the graveyard walls at night, to throw a fistful of the ashes of Nanabhai Bhatt over Shireen’s grave, so they could be united in death.

When I question him about the communal situation in Bombay, he says that it changed after the demolition of the Babri Masjid in Ayodhya in 1992, when blood flowed in the streets of Mumbai. A group of people led by Sunil Dutt felt the need to uphold the secular principles of the Indian Constitution, but those willing to come forward were few. When I probe him a little more, he refers to the Sachar Commission, which has stated that there is an institutional bias against Muslims. His last directorial film, Zakhm, was denied the censor which is certified by the Central Board of Film Certification. The BJP Government was at that time in power at the Centre and in the state of Maharashtra. Since he felt that his emotional state was not getting expressed in films, he has taken to writing and using public platforms to express his dissenting views. To clarify that he is not just a spokesman for the Muslims but for all the oppressed, he mentions that he took up the cause of the Kashmiri Pundits driven out of the Kashmir Valley, and publicly reproached a Hurriyat leader for not standing up for them.

Like the confluence of Ganga and Jumna, Mahesh is the embodiment of two distinct religious and cultural traditions, with all their richness, conflicts and contradictions. He says that, “I don’t fit into any of the religious categories, but would give my life for each of them to practice it”! With Promethean courage he is fighting for an India where the principles of secularism should become a living reality, and diversity of religious beliefs and cultures is given due respect. One admirer of Mahesh Bhatt has accurately described him as, “a one man peace brigade, building bridges across South Asia”. For Mahesh, the journey from India to Pakistan is the same as that from Sivaji Park to Pali Hill; on arrival in Pakistan he declared “I’ve met my mother”!

You may also like: