Written by: Mahnoor Fatima

Posted on: May 18, 2020 |  | 中文

| 中文

The Lahore High Court

Upon seeing the city of Lahore for the first time in 1809, British officer Lord Charles Metcalf remarked that Lahore looked to be, “a melancholy picture of fallen splendor. Here, lofty dwellings and masjids [mosques], which fifty years ago raised the tops to the skies and were the pride of a busy and active population, are now crumbling into dust.”

So begins historian William Glover’s study on Lahore, “Making Lahore Modern”. Glover concludes that colonial Lahore was made as an active collaboration between the British Raj, and the existing powers left behind from the glory days of Lahore. While the Old Shehr (City) of the Mughal era was narrow, confusing, and chaotic, the British sought to bring about a way of living that was structured and orderly. But at the same time, local elements needed to be added to make colonial assimilation into local culture appear more natural, as a continuation of the great rulers who ruled the city.

The architectural style of most of the buildings in colonial Lahore is called Indo-Saracenic or Mughal Gothic. Indo-Saracenic architecture came about in the aftermath of the revolt of 1857 and the subsequent dissolution of the East Indian Company. Prior to this, the dominant form of architecture was called Palladian, a geometric structural style with lime plaster. Palladian was designed by Sir Herbert Baker and Sir Edwin Lutyens, who were the leading architects of the buildings in the colonial centers of Madras, Calcutta, and Bombay. It was meant to serve as an example of British excellence, and familiarity in the face of a changing, nationalist India.

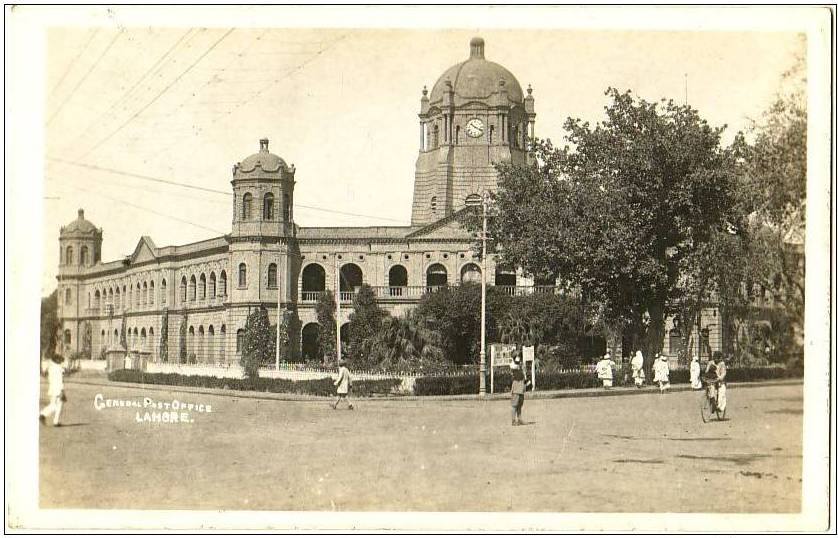

There are Palladian buildings present in Lahore, such as Lawrence & Montgomery Halls (where the National Library is currently housed), The Governor’s House, Provincial Assembly, Tollinton market, various churches and the Government College Building (now Government College University). The General Post Office Building (GPO) Lahore, built by Sir Ganga Ram for Queen Victoria’s 1887 Jubilee, is also in Neo-Palladian style; its structured, geometric façade with domes on top, closely resembles a Victorian-era Gothic-style school.

But Indo-Saracenic architecture served to disrupt this idea of British dominance by engaging local art and design. This was an amalgamation of traditionally Mughal and Indo-Islamic features like geometry, calligraphy, kash kari, with Victorian and neo-classical elements like columns and towers. Indo-Saracenic architecture featured prominently in administrative buildings within colonial Lahore.

Indo-Saracenic architecture covers most of the Main Mall Road, stretched from the Civil Secretariat (home of the Punjab archives, and Anarkali’s Tomb) to Lawrence Garden. Notable examples of buildings within the colonial sector of Lahore are the University of Punjab, The High Court, The Lahore Museum, and many more.

Scholars have different opinions about the effectiveness of Indo-Saracenic architecture in fulfilling its goals. Some argue that it did not offer enough representation to earlier architectural grandeur, it was neither wholly British nor wholly Indian. Local people were not unaware of the British’s blatant attempt at legitimizing their rule. However, others are more sympathetic, arguing that architects had a genuine love for the architecture as they understood it, and promoted local artisans who brought variety and creativity into government architecture, and their efforts should not go unnoticed.

One individual stood out as a distinct voice, interested in not only creating a personal legacy, but creating more collaboration between skilled Indian craftsmen and British aesthetics: Sir John Lockwood Kipling.

Sir John Lockwood Kipling (1837-1911), the father of writer Rudyard Kipling, was instrumental in creating the aesthetics needed to construct this kind of hybrid architecture. Originally stationed in Bombay, Kipling toured Punjab, North-West India, and Kashmir to study local craft-makers in the hope of replicating and commercializing their products.

As principal of the Mayo School of Arts (now the National College of Arts, also designed in Indo-Saracenic style), he encouraged his students to take inspiration from the Sikh and Mughal motifs already abundant in mosques, shrines, and havelis (Indian mansions) of Lahore. When England asked for artifacts and Indian products to sell and keep, the elder Kipling would send plasters or copies, so as to retain the originals within India.

One of Kipling’s students, Bhai Ram Singh was hired by executive engineers Sir Ganga Ram and Rai Bahadur Kanhaya Lal in the Public Works Department, the body of the government responsible for the creation and construction of both the Civil Lines and the Lahore Cantonment. Bhai Ram Singh designed the White, dome-shaped pavilion on Charing Cross to mark Queen Victoria’s Jubilee, combining the white plaster elements from Neo-Palladian architecture with Kipling’s Indo-Islamic Designs. On the other hand, Sir Ganga Ram, was responsible for many of the buildings mentioned earlier, but also schools like Aitchison, the Ganga Ram Hospital (that is named after him) and what was then the small suburb of Model Town.

As Lahore shifted from the colonial to a post-colonial, post-Independence city that it is today, rapid urbanization has allowed the city to expand further away from the Old City and Colonial centers. However, the administrative buildings have remained under the control of the government, and people often venture back into Colonial Lahore for business or recreation.

Scholars will continue to argue whether Lahore’s colonial architecture was meant to innovate on local traditions or impress “the natives” with imperial grandeur. However, these colonial buildings have survived the test of times, including the turbulence of the Partition. Today, Lahore’s charm lies in the juxtaposition of the Old City of Lahore, parts of which have recently been restored, with the stately and wide boulevards of its rich Colonial sector.

You may also like: