Written by: Jalal Hussain

Posted on: August 23, 2017 |

Imran Khan with the 1992 Cricket World Cup, Islahuddin Siddique with the 1978 Hockey World Cup, Jahangir Khan with his 1991 British Open Squash Championship trophy, Muhammad Yusuf with his 1994 IBSF World Snooker Championship Trophy

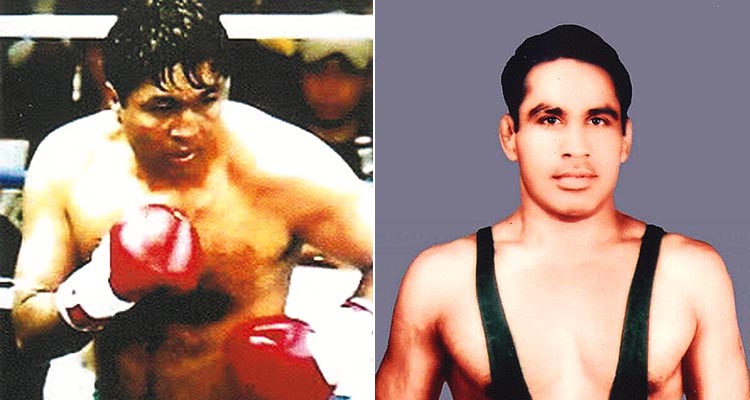

Sport in Pakistan has been marked by dismal institutional support, with a sports budget that is the lowest in South Asia. Pakistan has participated in Olympics since 1948 and has won a total of 10 medals: 8 of these came from field hockey; a bronze for wrestling in 1960 in Rome was won by Mohammed Bashir; and another bronze in middle weight boxing in the 1988 Olympics, Seoul was won by Hussain Shah. However, the startling fact is that Pakistan has not won a medal for 24 years.

Pakistan’s hopes for the Olympics used to be pinned on field hockey, from its first gold in Rome in 1960, right through to the 90s, when it continued to dominate the sport. It won the hockey World Cup four times and made it to the finals six times. The administrative skills of Air Marshall Nur Khan were instrumental in this success, as he did two stints as the President of Pakistan Hockey Federation, with a total of ten years. Such has been the decline of hockey in Pakistan that in the 2014 World Cup, Pakistan was not even able to send a team for the event.

In the field of squash, the story is similar to that of hockey, but with the difference that members of an extended family from a small village called Nawakille, outside Peshawar (which didn’t even have a squash court), began to dominate the sport from the 50s to almost the end of the century. It began when Hashim Khan began his unchallenged domination of the sport, with his seven wins of the British Open (the equivalent of a world cup) in the 1950s. His relative Roshan Khan, and then his younger brother Azam Khan, followed with four wins of the British Open. After Mohibullah Khan’s victory in 1963, Jonah Barrington of Britain and Geoff Hunt of Australia became the champions, and the Khans of Nawakille lost their supremacy. After a hiatus of almost sixteen years, the Khans staged a comeback with Jahangir Khan’s win of the British Open in 1979. This began his reign as arguably the greatest player ever, accumulating 10 British Open titles and 6 World Opens. Jansher Khan followed with 8 World Opens and 6 British Opens. However, since Jansher lost the British Open in 1998, no Pakistani has made it to the top.

The popularity of cricket picked up as Pakistan’s performance in both hockey and squash declined rapidly after the 90s. Talented and mercurial, the team won accolades against all odds with wins of the 1992 World Cup and the 2007 ICC T20, to becoming the number one ranked test team in 2016, all the while defying logic and pundits expectations. At its recent outing to the ICC Champions Trophy in June this year, it was the lowest ranked team in the competition, coming into the global event with a string of humiliating defeats. However, Pakistan managed to win the tournament in a spectacular fashion by defeating arch rivals India in the finals. A famous epithet about the Pakistan cricket team is: “The only predictable thing about Pakistan is their unpredictability.”

Other sports that have made their presence felt at the international level include snooker, polo, and tennis. More recently, our snooker players have been doing well in international competitions, and this sport has been gaining in popularity. Muhammed Asif became the World Amateur Snooker Champion in December 2012, Muhammed Yusuf had won it before him in 1994, and Saleh Mohammad had been the runner up in 2004. Polo, an elite game with a niche audience, has a respectable and consistent record. Hissam Hyder, with a handicap of 6+, is its most famous luminary currently. Aisam ul Haque is the only professional tennis player who has made his mark on the international arena. Though ranked amongst the top ten in the doubles, his highest ranking in the singles was 125th. He has reached this level because of the support of his family, and the Pakistan Tennis Federation’s contribution in his rise has been next to nil.

There are multiple reasons for the steep decline of sport in Pakistan, foremost among them being the lack of institutional support from the government and their failure to improve the existing infrastructure. There are no state of the art squash academies through which we can produce international quality squash players. The squash legends that Pakistan produced were self-made and arose despite the unsupportive system. As far as hockey in concerned, Pakistan failed to keep pace with the rest of the world, since hockey rapidly evolved with the advent of astro turf surfaces and Pakistan failed to adapt to the new skill set required. Pakistan hockey has also been chronically cash strapped, as the focus of corporations and the government has been on cricket, and the Pakistan Hockey Federation have been unable to offer the facilities or incentives to players that an international team needs. With no serious attempt by the government to organize sports in schools and at the grass root level, handicapped by outdated equipment and training methods, and with coaches who are out of touch with the latest scientific techniques, Pakistani sportsmen stand little chance of success at the international level.

Weighed down by corrupt and incompetent bureaucracies, the various sports boards are staffed on the basis of patronage. Their role as impediments rather than facilitators of sports is portrayed well in the film “Shah” about Syed Hussain Shah, who won the only medal for Pakistan in boxing at the Olympics in 1988. Symptomatic of what really ails sports in Pakistan, there were twice as many officials as athletes that went to the Rio Olympics in 2016, and these seven athletes were unable to get beyond the qualifying rounds. Nepal had the same number of athletes, but with almost one-sixth of the population.

You may also like: