Written by: Jovita Alvares

Posted on: October 19, 2020 |  | 中文

| 中文

'Milkmaids' by A.R. Chughtai

For Part 1 of the Great Artists of Pakistan, click here

In its history, Pakistan has undergone various cycles of cultural evolution, which trickled down into the traditions and practices of its artists. The traditions of the Mughal empire slowly devolved and fused with the artistic movements brought from Europe by the colonial British. When the British left the Subcontinent and Pakistan became an independent country, that shifted how artists engaged in their pre-colonial legacy and colonial artistic traditions. But also, the creation of a new country led to local artists forging a uniquely Pakistani identity. This essay briefly delves into the works of some of Pakistan’s most renowned artists and how their practices slowly gave rise to the collection of artists that make up the country’s contemporary art scene.

Abdur Rehman (A.R.) Chughtai is considered the first significant modern artist from Pakistan. Born in 1897, Chughtai is largely known for his intricate watercolor miniature paintings, and is credited for developing his own unique style that meshed together his interest in Islamic traditional art and knowledge of Western Art movements like Art Nouveau.

A student of the Mayo School of Arts (later changed to the National College of Arts or NCA), he also taught there while continuing his practice and showcasing works there. Chughtai was also an avid printmaker and went on to perfect his etching skills in London in the 1930s. Through his sixty years as an artist, he is known to have created over two-thousand paintings, thousand pencil sketches and almost three-hundred prints. According to art critics, the Muraqqa-i-Chughtai, an illustrated publication of Mirza Ghalib’s poetry, is considered his magnum opus and the most well-produced book in the country.

Additionally, he designed stamps, coins and other labels for the newly partitioned Pakistan, which included the first logo for the Pakistan Television Corporation (PTV). Chughtai was awarded the ‘Khan Bahadur’ by the British Empire, and the ‘Hilal-i-Imtiaz’ and the ‘Pride of Performance’ awards by the President of Pakistan.

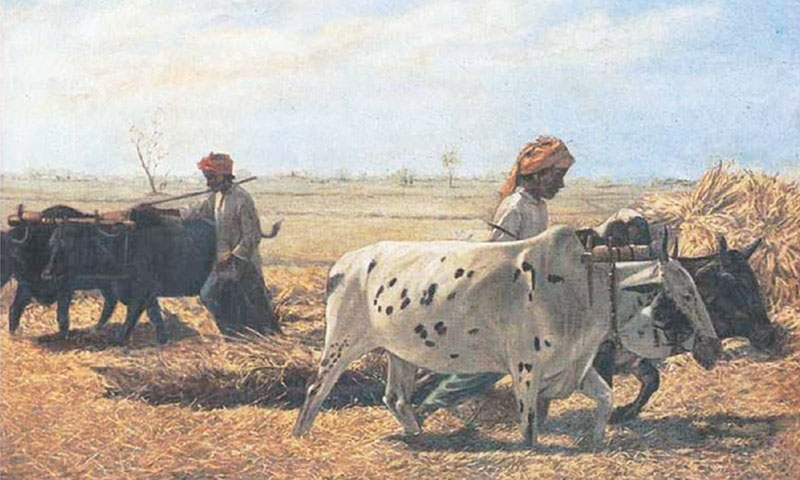

Ustad Allah Baksh was also born around the same time as Chughtai. Both artists worked during the twilight of British colonial rule, and the establishment of a newly-created Pakistan. Baksh was a painter and calligrapher, known for his classical landscapes that depicted the rural life of the subcontinent. Unlike Chugtai, Baksh did not have formal training as an artist. He became one out of financial necessity, training under Ustad Abdullah, an already-established expert on miniature art. Baksh became a background painter for a Photographic Studio and a court painter. He started his training by mimicking Western paintings, which taught him about realism and perspective, but later created works that were laden with local myth and tradition.

Unlike some of his contemporaries who aimed to push forward a new indigenous art style, Baksh took his understanding of Western art and style to create elaborate figurative and scenic paintings much like a Romantic painter; he often took inspiration from Shakespearian plays and the works of Eugene Delacroix. He was awarded the Pride of Performance award in 1963, and is considered as the pioneer of modern landscape and figurative painting in Pakistan.

Another equally important contributor to the foundation of modern art in Pakistan is the dynamic Shakir Ali. Born in 1916, Ali had extensive art training, both from the prestigious J.J. School of Art in Bombay and the Slade School of Art in London. He joined the Mayo School of Art as a teacher and became the institute’s first principal when it became the NCA. He became an influential figure within the local art scene and his international knowledge, from his training in Paris and Prague, was imperative in redefining the art of the newly partitioned country and keeping it up to date with international art movements.

Influenced by Cubist art and European myths, Ali slowly found his own style through a unique stylization of humans, horses and cattle in his paintings, often in stark red colors. The objects in his work were simplified down to bold lines and powerful structures; he often painted birds locked in cages to signify a loss of personal freedom in a world of conventionalities. Later he also began dabbling with the use of calligraphy, and was one of the first artists to incorporate that form into his art. He was awarded the Pride of Performance in 1966, and is widely known as the father of Modern Art in Pakistan.

Jamil Naqsh was a student of Shakir Ali, who went on to establish himself as one of the last great modern painters of Pakistan, before his unfortunate demise last year. Naqsh was born in 1939 in Kairana, British India (now in UP), and later moved to Karachi after Partition. He studied Miniature painting at the NCA and left before completing his schooling. He went on to become a dedicated miniaturist under the tutelage of Ustad Muhammad Sharif, and stories are told of how he began work at dawn and finished at dusk, without taking breaks in between. After his training, Naqsh worked for advertising agencies and as a Studio Art Director. He had his first solo exhibition at the Lahore Arts Council in 1962 and then in the Karachi Arts Council, the latter of which won him a gold medal from the Council.

Naqsh’s unique style depended on simple objects which possessed multiple layers of meanings, rendered in different ways. His practice mostly revolved around the pigeon and the female form, which to him embodied a sense of harmony, memory and nostalgia for his travels around India in his adolescence. His last exhibition explored the ruins of Mohenjo-Daro with that same subtle layering, and has been on display in the Jamil Naqsh Museum in Karachi. The artist was celebrated with the Pride of Performance Award in 1989, and the Sitara-i-Imtiaz (Star of Excellence) in 2009.

Contemporary art in Pakistan owes a great deal to these painters, who pushed boundaries and created new styles and techniques to be emulated for generations to come. The above few are just a handful whose work forged a path for young artists and art students today, and their dedication has in retrospect established the artistic identity of a new country. Looking back at their practice is imperative for understanding the genesis of art in Pakistan and how they have cast their influence on the generations of artists that have followed.

You may also like: