Written by: Nimra Khan

Posted on: December 16, 2021 |  | 中文

| 中文

Old photos hanging in the front and a blurred background projects memories. (Credits to Vasl Artists Association)

“In Loving Memory of…” is a collaboration between Razin Rubin and Haider Ali Naqvi. It is presented by Vasl Artist’s Association as part of their ongoing project “Museum of Abandoned Spaces (MOAS)”, which aims to challenge the boundaries of art and question the idea of a museum as an established institution that conserves, preserves, collects, and displays objects of historical, cultural and academic significance. It achieves its goal by creating what can be seen as an anti-museum that offers ephemeral experiences in ordinary spaces that have been deserted, bringing them back into use, and instigating a dialogue around them.

With this particular project, personal possessions that speak of collective histories are displayed and studied, recreating abandoned rituals so they may not be forgotten even if they have been discontinued. This makes it an alternate kind of museum that operates on a micro level and resists against such constricting labels in the process, becoming an embodiment of what a museum represents as a notion.

Edibles in the table while photographs hanging on the wall (Picture taken from Vasl Artists' Association)

The project utilizes the intimate interior of a restaurant to create a sort of memorial to abandoned ritual celebrations, namely Christmas, that not only laments and honors personal histories but brings them back to life in the most poignant fashion. Rubin’s practice often looks at the spaces that were once occupied by the people who are no longer with us, and the objects and the furniture that they owned and used which survives them and become emblems of the memories created around them. She often uses drawing, photography, and installation, all of which she brings together here to create a wholesome experience.

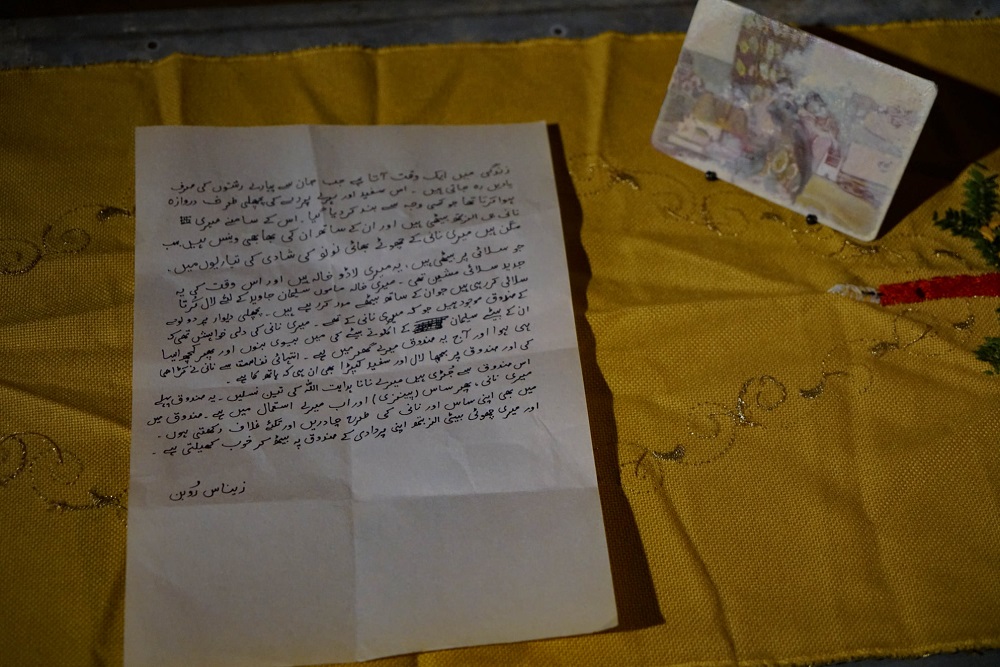

A letter detailing the family's connection with a suitcase (Picture taken Vasl Artists' Association)

The project centers around a couple from Sukkur, Sindh, Sulaiman Javaid and Pansy Wilson, who were happily married for 29 years before being separated by death. Every Christmas they would start their day by dressing up and going to church, and when they would return, all their friends, family and neighbors would come over and they would enjoy the feast they prepared. These memories are resurrected in little pockets, from objects previously owned by the couple, the dinner table set up the same way, with the same foods sourced from family members or the family recipes. The audience is invited to relive these memories with the artists, of rituals that have since been abandoned following the deaths of these individuals.

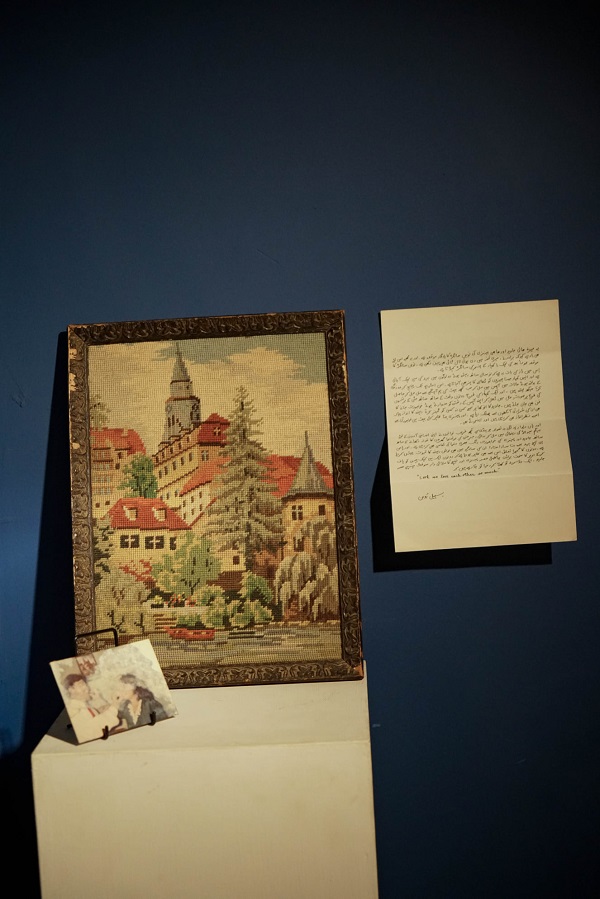

A letter hanging, a photograph and a painting on the table. (Picture credits to Vasl Artists' Association.)

While time and the monotony of everyday life helps provide comfort and create a distraction that helps heal and forget the wounds created by loss and grief, it is common for special occasions to dig those wounds back up. It then becomes pertinent to commemorate not only this occasion marred by loss, but through it celebrate lives well lived. The ritual candles and dim lighting set a somber mood, yet the old merry tunes and festive décor turn it into bittersweet remembrance. It becomes the perfect occasion to reminisce the lives of those who made it most special; the space is filled with memorabilia arranged into installations every few steps, each a postcard-sized painting and a letter penned in Urdu, standing like shared stories around a dinner table, or a cup of tea in the living room.

These installations are a product of zoom conversations with relatives and an exchange of old family photographs, in response to which Naqvi created paintings that resemble fading moments. Placed next to these objects and handwritten letters describing the furniture, spaces, events, and people seen within them, they become like ghostly apparitions. A portion of a living room with a chair and table accompanied by a decorated Christmas tree, an old briefcase sitting ajar and abandoned, a sari hanging from the ceiling, an armchair and a photo album, a dresser draped with an embroidered purple dupatta. It is as if one is walking through the remnants of a home, rebuilt from scraps of memories, creating a strong sense of nostalgia.

These possessions and experiences allow us to confront the significance of our loved ones beyond just their corporeal presence and reflect on how much of themselves they leave behind in everything they touch, how much things change when they are no longer there. These possessions carry the essence of their former owners and their imprint in the creases and etchings of time. And through them, we get to witness them, even if for a few moments, and become a part of the vestiges of their existence.

A profound dialogue is created between art and space, bringing art out of conventional bounds to generate an alternate experience. The installations make use of the architecture and décor of the space in such a way that it becomes difficult to separate the two and establish which elements are pre-existing and which are brought in by the artists. This ties in successfully with the larger directive of the MOAS, which is “to break away from conventional forms of art in the city and to generate dialogue around what constitutes art, its longevity, and who has claim over it.”

You may also like: