Posted on: November 25, 2013 |

|

Karachi, the eternal city of lights, a circus of fire tricks and modern day gladiators, a canvas smeared with blood and smoke. From the cycle of violence, emerge voices spread over various mediums, constantly innovating to make themselves louder and more conspicuous. Fatima Munir is a young voice from Karachi, a graduate of the Indus Valley School of Art and Architecture in 2012. Her artistic expression dabbles in both fine art and textiles, merging the two to amplify her resistance against the brutality of the prevailing status quo.

Her solo exhibition titled “Aamney Samney-Andhar Bahar” (Face to Face-Inside Outside) opened at Islamabad’s Rohtas Gallery mid-week. The show consisted of six toy guns wrapped in fabric and six fabric wall hangings. The toy guns serve not only as miniature guns, fundamental in Karachi’s violent daily life, but are figurative of the notion that guns have becomes toys in the hands of men; reality and life are simply child’s play. The artist employs needlework, a common practice in the region, used to adorn homes and calm the restive soul of the individual. She juxtaposes the two in her design to “sing the songs of my mind”.

The art display “Samney” features a black cloth gun against the backdrop of the media, with a headline that reads, “Children are hungry to find their voice”, loudly echoing the artist’s motivation, but the toy gun serves as reminder of the silence that prevails. “Aamney”, portrays a gun wrapped in a white cloth in front of a wallpaper of Rs 5,000 notes, indicative of the dead bodies encased in white clothes buried for the greed or desperation for money.

The calligraphy on the fabric blinds bode a cautionary admonishment, “Aaj mein kal tum” (Today it is me, Tomorrow it will be you), “Qaatal hum sab hain” (We are all murderes) and Koshish (Struggle), an attempt by Fatima to knit society together. Munir explicated in her statement that she sings the tale of Karachi, “about the compromise of living and raising a family in one of the most dangerous cities of the world. About the despair that stare me in the face everywhere I look. And about the grief that we all must overlook to survive.”

|

The theme of Shakil Saigol’s latest offering is women, to the exclusion of any other subject matter. Reflecting his versatility, this exhibition is a far cry from the zebra series, which had muscular males and seductive women in close proximity to full bodied zebras. While his message is cerebral and unambiguous, that denying women education is another form of bondage, his vehicle of expression are semi-nude nubile women draped in sarees.

The women are reminiscent of Indian miniature paintings that seem to have heavily influenced Saigol’s style. His courtesans and durgas are traditional in their appearance, with hair tied in a bun, encircled by a string of jasmine, wearing a choli or nothing at all, and wrapped in a sari. However, it is the context of these doe-eyed but passive women that makes the paintings potent. Most of these beautifully adorned women are in some kind of shackles, while books hang from the ceiling with chains around them, a forbidden item. A graceful nude, with a sari thrown over one shoulder, walks through a luxuriant world of trees and foliage carrying a brain in a birdcage. Brain dead!

With the juxtaposition of women painted in black and white in the background, denoting a bygone age, and contemporary ones painted in colour, the message is that nothing has changed over time, or “still we are like that only...”A woman painted in hues of black and grey sits in the background with a deadened and a somber expression, while a fully made up young woman is captured wrapped in a colourful sari painted with the mastery and detail of a miniaturist, but she seems to be cutting her tongue, as a desktop computer lies beside her, locked in chains. Not surprisingly, Malala, a heroic symbol of resistance to those denying women education, also makes an appearance in a couple of his paintings. While her gray eminence hauntingly stares into the future, colourful semi-clad women in the foreground lovingly clasp books to their chest, but their hands chained to the books. Using symbols of Indian mythology, the powerful Hindu goddess Durga is depicted armed with books and pen, rather than a sword or a trident, while courtesans dance like puppets with their hands chained.

His meticulous detailing and quality of draftsmanship is manifest in his painting of sarees, which he considers an art form. This series celebrates sarees, his paintings capturing the richness of their texture and designs, ranging from kanjivaram to banarsi.

In his write-up for this exhibition, Saigol dilates about his concerns as expressed in this series, that “Only 18% of women have had 10 years of schooling. The drop out rate at the elementary level is 30%”. The Taliban, he reminds us, have shut 400 schools, where 40,000 girls were enrolled, but he also holds the successive governments responsible, as they only spend 2% of the budget on education. His wife, Rehana Saigol, herself a well-established fashion and jewelry designer, explained that his paintings are all about the self-expression denied to our women.

|

The subtle pervasive quality of man that exudes from his surroundings is the subject of R.M. Naeem’s recent art display at the Tanzara Gallery, which was inaugurated November 21. The internationally acclaimed artist whose fortunes shined when he left his brother’s shop in Mirpurkhas to join the National College of Arts, a world that, as he explicated “was a cultural shock for me, a place seemingly miles apart from my rural background”. His cultural transition is reflected in his realist imagery of the spiritual and intellectual transition of man.

Much like his previous works, Naeem remains invariable with his array of human figures and the use of urban structures such as road signs. The protagonists in his portraits are bald, in order to create a sense of uniformity that highlights his message of peace; his belief that humans throughout time and space are akin, which should allow for harmonious dialogue, irrespective of the prejudices of caste or class systems rampant in today’s society. The faces and bodies are stripped of arrogance, the eyes always gazing down, representing characteristics of a mystic, modest and submissive being towards a greater entity. The urban tools, which are recurrent in most of his images annotate on perceptions of law and order. They play a two-fold role of the limitations and barriers that can either aid or challenge us in our routine, while also relating to the spiritual guidance designed as beacons to the right path.

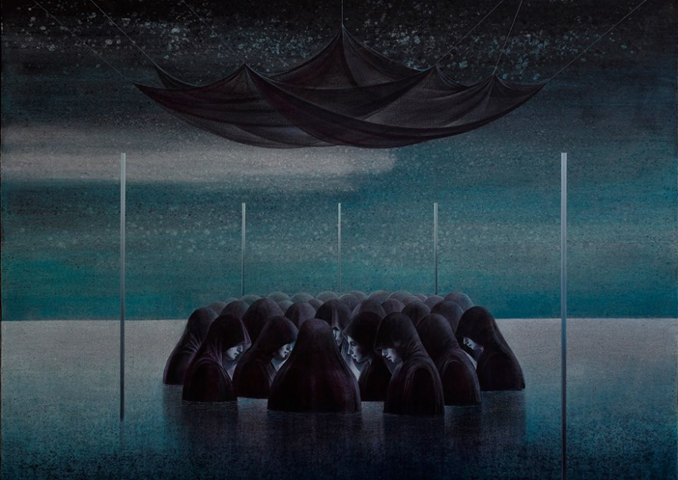

The captivating portrait of a round congregation of women covered in black, floating in a sea that reflects the colours of the sky above, epitomizes both the limit and nothingness of the human entity, but once again there is the obstruction by five poles containing the women, confining them to the space that has been created for them by man. The poles also prevent the women from being lost or drowned in a sea of egotism, hence representing a spiritual circle. Heads are often illustrated sans a body, the head epitomizing the intellectual capacity and growth. In one of the portraits, an adult’s head emerges from a child’s cranium fiddling with idea of transition and growth. In another image, the adult’s facial visage is inhabited by the body of an infant, both of which are confined to a cylindrical box.

The experience of R.M Naeem’s interpretation of man and his world is a metaphysical one, although the symbols on the canvas are manufactured, they transcend into the spiritual creating a dual narrative.

You may also like: