Written by: Haroon Shuaib

Posted on: October 18, 2021 |  | 中文

| 中文

A Bugti Man (credits to Muneer Marri)

Placed very strategically on the convergence of three of the four provinces of Pakistan, Dera Bugti district of Balochistan shares its borders with districts Rajanpur of Punjab, Jacobabad of Sindh, Jaffarabad, Naseerabad, Bolan, and Kohlu districts of Balochistan. But it is not just geo-strategic location that adds to the significance of this isolated district of 10,159 square kilometers with a population of just over 300,000. This region, given the status of a district in 1983, has immense geological, archeological, political and cultural wealth, most of which still awaits discovery.

Situated in the westward continuation of Sulaiman Range, pointing towards Quetta node, Dera Bugti region came to unprecedented prominence after discovery of large reserves of natural gas. Pakistan has four major gas fields out of which three are in Dera Bugti including Sui, Pir Koh and Loti Gas fields. Fourth is Uch Gas field, which is in the neighboring Naseerabad District. Natural Gas was discovered in Sui in 1963, and during the same year, the first gas supply plant was established. Till then the region was so obscure that according to some accounts, the discovery point didn’t even have a name. It was named Sui after a nineteenth century fortress of the same name that is a few kilometers away from where the plant was set up. The Sui gas field is considered to be the largest in Pakistan, with an estimated reserve of 1.6 trillion cubic feet as of 2017.

Dera Bugti summers are long and sweltering, winters are short and cool, while it is dry, the year round. Dera Bugti district is situated in the Middle Indus Basin’s Nari Gorge. Topography of the area is rugged to semi rugged and largely barren. A British archeologist and writer, Sylvia Matherson, wife of an engineer posted at the Sui gas field in the ‘60s, spent five years in the area and wrote a fascinating book about the land and its people called The Tigers of Baluchistan, which was first published in 1967. ‘Flat topped or carved by the winds into crenellated battlements and gigantic, bearded faces, the Lower Siwaliks emerged from the dawn mists in delicate shades of lavender-rose to resolve into harsh reds and browns and oranges; later they would dissolve into the midday heat in waves of sandy camouflage and still later they would stand in dramatic silhouettes of deep purple and grape-blacks against the startling scarlet, gold and flame of a desert sunset.’ She wrote. British officer John Jacob, serving with General Keane, travelled through the area in 1839 and wrote, ‘From April till October, the heat in this part of the world is more deadly than the sword of a human enemy and scarcely an escort at this time marched through the country without losing many men for this cause alone…. The place is remarkable for its dust storms of almost incredible violence and density. They occur frequently at all seasons of the year, sometimes changing the light of midday to an intensity of darkness to which no ordinary night ever approaches… sometimes accompanied by blasts of the simoom, a poisonous wind which is equally destructive to vegetable and animal life.’

During the 19th and 20th century, the area also drew the interest of archeologists. Intensive and meticulous biostratigraphic search and collection of evidence in the Bugti hills unearthed over a dozen fossiliferous species of the Early Oligocene to Late Miocene eras. ‘Bugti fauna’, as archeologists refer to it, offered its most central puzzle piece in 1910 as the bones of the Baluchitherium (A hornless rhinoceros) were found in Dera Bugti. Other interesting discoveries include fossils of seven-meter-long snakes, crocodile, fish and a huge turtle shell that is estimated to be 63 million years old.

Dera means abode, and Bugti is the name of a Rind Baloch tribe. Bugti is a quaint tribe known for its ferocity and gallantry. They are the descendants of the relatives and followers of Gyandar, a cousin of Mir Chakar Khan Rind, a celebrated Baloch chieftain of the 16th century. Edward G Oliver wrote about Balochis in 1890, ‘War is looked upon as the first business of a gentleman, and every Balochi is a gentleman.’ No matter how often they clashed in battle, the British had nothing but praise for the chivalry of their Bugti opponents who, ‘refused to surrender against heavy odds, preferred to fight hand to hand, never took advantage of the terrain, and never shot their enemies in the back’. Exasperated by incessant attacks and raids on their cantonments, in 1846 the British declared the defiant Bugti tribe outlaws and put a price of ten rupees on every man’s head, dead or alive. The Bugti territory was one of the last to fall to the British colonial rule.

Bugtis speak an eastern dialect of Balochi, based on Persian with a large percentage of Sindhi and Punjabi words, though their traditional songs are all in an archaic dialect, which even the local singers find hard to understand and know only by rote.

Besides the iconic profile of the hirsute tribesmen with finely curled moustaches and long locks of hair, Bugtis are also known for their traditional dress. A baggy trouser or ‘Bugti shalwar’, called ‘Kanavez’ can contain as much as twenty or more yards of material. The shirt is finely-smocked with hundreds of gathers falling from the yoke. The shirt and trouser are complemented by a folded shawl called ‘Pushti’. This shawl keeps the tribesmen warm in cold weather and keeps out dust and sand, while draped over a gun stuck in the ground, it forms a little tent to shelter from the sun, and lastly folded into a pad it makes a cushion to soften the jagged rocks. Spread on the ground, it serves as a prayer mat and wrapped around the forearm, it protects during a fight.

Bugtis also have their peculiar leather sandals or ‘Chawat’, as they are called in Balochi. These sandals have gained popularity as a footwear of choice across the country in recent times. With a sole made out of recycled pieces of rubber tyres, these hand-made sandals are known for their durability, uniqueness, and fineness. Bugtis also sometimes wear ‘Sawaz’, a sandal made from the woven leaves of dwarf palm. Bugti headgear is yards of twirling turban tied over a cap called ‘Putak’, which is heavily embroidered with tiniest pieces of mirror, often worn at an angle to show one corner among the turban folds and sometimes worn alone without the turban. With the exception of the cap, all Bugti robes are traditionally white. One of the reasons why the British failed to attract these warriors to recruit in the military was that the Bugtis refused to change their traditional attire or cut their hair or beards.

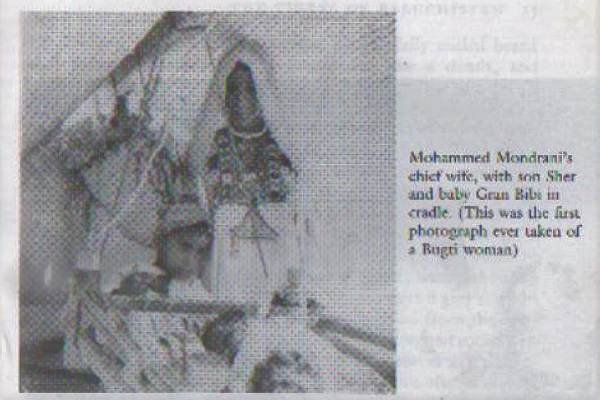

Sylvia Matherson notes, ‘The (Bugti) women make pieces of embroidery, setting small circles of mirror into their designs embroidered on oblongs of cotton material that would be appliqued on to the yoke of heavy cotton pushk dress worn by the women. When the dress itself wears out, the embroidery is removed and stitched on to a new garment. Bold circles and squares make up the designs, which vary slightly according to the clan and tribe.’ These loose shirts are topped over baggy trousers and long dupatta or chador called ‘Sirree’ are worn to observe purdah. The hand-made embroidery covers the ends of sleeves and the front of the dresses of women with an upsized triangular embroidered pocket down the hem. They are complex designs sewed meticulously without the use of any charts. The patterns are believed to be a continuation of the Mehrgarh civilization of 700 BC. Same motifs can be seen on the pottery found from Mehrgarh. ‘Generally women wear plenty of bracelets (Thawkh) and silver anklets (Paizeb) with many small silver ear-rings piercing the edges of the ears and called ‘Dur’. Married women on special occasions wear a nose ring called ‘Pulloh’, usually a bracelet sized gold ring with a ruby and supported by a gold chain or woolen thread to the top of one ear. The hair is divided by a front parting, heavily greased with sheep-fat and plaited in two braids, sometimes lengthened by adding long hanks of black wool and sometimes divided into many small thin plaits,’ chronicles Matherson.

In 2017, the first phase of 399 km long Kachhi Canal was completed. The canal brings water from Taunsa Punjab to Balochistan and 72,000 acres of command area in Dera Bugti district has become cultivable. The China Pakistan Economic Corridor, the modern agricultural technology and access to markets is bound to bring a new era of prosperity and openness to the people of Dera Bugti.

You may also like: