Written by: Haroon Shuaib

Posted on: August 27, 2021 |  | 中文

| 中文

A painting of China according to Marco Polo's account

The earliest European travelers often referred to China as Cathay. Marco Polo, born in 1254 in Venice, Italy was a merchant and adventurer who traveled from Europe to Asia in 1271, and remained in China for 17 years. His book, ‘Il milione’ – ‘The Million’, known in English as ‘Travels of Marco Polo’, is considered a classic piece of travel literature. The book described to Europeans the then mysterious culture and inner workings of the Eastern world, including the wealth and great size of China in the Yuan Dynasty. Marco Polo gave the West a first comprehensive look into China, Persia, India, Japan, and other Asian countries.

Marco learned the mercantile trade from his father and his uncle, who travelled through Asia and in 1269. The three of them embarked on an epic journey to Asia, exploring many places along the Silk Road until they reached what they described as ‘Cathay’. They were received by the Emperor Kublai Khan, who was impressed by Marco's intelligence and humility. Marco was appointed to serve as Khan's foreign emissary, and was sent on many diplomatic missions throughout the empire. As part of this assignment, Marco also traveled extensively inside China and saw many things that had previously been unknown to Europeans. He left China in 1291, to make his way back to Venice.

Though he was not the first European to reach China, Marco Polo was the first to leave a detailed chronicle of his experiences. His account of ‘The Orient’ was the first Western record of porcelain, coal, gunpowder, paper money, and some Asian plants and exotic animals that he noticed during his travel through Asia in general, and China in particular.

Another Italian traveler, Odoric of Pordenone, spent three years in Beijing, between 1323 and 1328. Odoric wrote a narrative of his travels, which have been preserved in Latin, French and Italian. Regarding China, his descriptions of the custom of fishing with tame cormorants, a traditional method in which trained aquatic birds are used for fishing in rivers, is particularly fascinating.

Niccolò de' Conti, an Italian merchant, explorer and writer, traveled to Southern China during the early 14th century. Conti’s accounts are contemporary, and fairly consistent with those of the Chinese writers such as Ma Huan and Fei Xin. The man ‘from Cathay’, referred to in a letter received by Christopher Columbus in 1474, might have been De' Conti.

After returning from the East, he met Pope Eugenius and shared his experiences. This letter notes some fascinating observations about the China of the 14th century, ‘One of them (from Cathay) came to Eugenius….. and I had a long conversation with him on many subjects; about the magnitude of their rivers… and on the multitude of cities on the banks of rivers. He said that on one river there were near 200 cities with marble bridges… everywhere adorned with columns. This country is worth seeking by the Latins, not only because great wealth may be obtained from it, gold, silver and all sorts of gems and spices, which never reach us. We have also a great deal to learn from its learned men, philosophers, astrologers, the skill and art of governance, as well as how they conduct their wars’.

Gaspar da Cruz of the 15th century was a Portuguese missionary, who travelled to a small island in the Guangzhou bay. Cruz wrote a book about China, ‘Tratado das cousas da China’, published in 1569. This book played a key role in shaping the European view of China in the 16th century. Interestingly, his book mentions communication between the Portugese and the Chinese with the help of Chinese interpreters, ‘but never a Portuguese person speaking or reading Chinese’. Da Cruz was, however, curious about the Chinese writing system, and gave a report of it described as ‘the first Western account of the fascinatingly different Chinese writing’.

Matteo Ricci, an Italian priest who created the Kunyu Wanguo Quantu, a 1602 map of the world written in Chinese characters. He entered Beijing in 1601, invited by Emperor Zhu Yijun, who sought his services in matters such as court astronomy and calendrical science. He also worked on translating Confucian classics into Latin. He travelled to Beijing via India and Macau in 1582. Ricci studied the Chinese language and customs, and became the first Western scholar to master Chinese script. He traveled to Guangdong's major cities, Canton and Zhaoqing, finally settling there at the invitation of the governor of Zhaoqing.

It was in Zhaoqing, in 1584, that Ricci composed the first European-styled world map in Chinese. No prints of that map exist today. It is also believed that during his stay in Zhaoqing, Ricci and his associate compiled a Portuguese-Chinese dictionary. Ricci was known for his appreciation of Chinese culture in general, and he even adopted the Chinese dress. There is now a plaque in Zhaoqing to commemorate Ricci's six-year stay there, and a ‘Ricci Memorial Centre’.

In 1601, Ricci was invited to become an adviser to the imperial court of the Wanli Emperor, and became the first Westerner to be invited into the Forbidden City. This honor was in recognition of Ricci's scientific abilities. The Emperor patronized him with a stipend as Ricci compiled ‘Record of Foreign Lands’ - Zhifang Waiji, China's first global atlas. Ricci died in Beijing in 1610. According to the Ming Dynasty code, foreigners who died in China had to be buried in Macau. In light of Ricci's contributions, the Emperor granted permission for Ricci to be buried in Beijing.

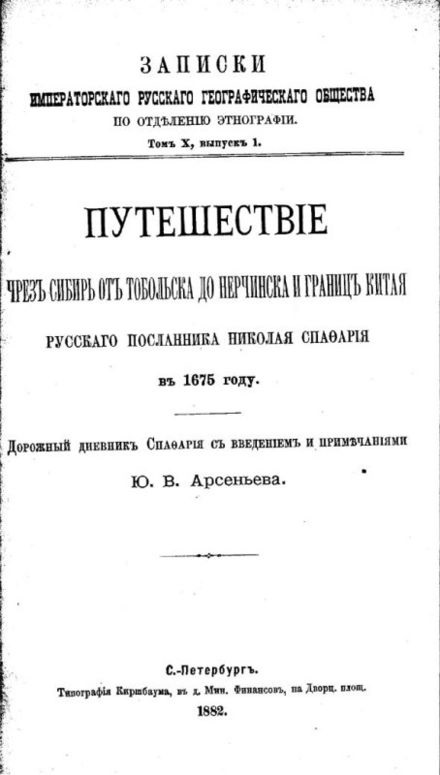

Nikolai Spathari, a Russian writer, diplomat and traveler, also contributed to the knowledge about China to the world. He was named ambassador of the Russian Empire to Beijing in 1675. His main tasks as the ambassador included settlement of border incidents between the two empires, establishment of trade relations, and a survey of the newly incorporated Russian lands along the Amur River. Spathari crossed into Beijing via Hebei River. Upon returning to Moscow, Spathari put together three volumes of notes, ‘Travel notes and Description of China’. His records were later used by many western travel expeditions to China.

Title Page of Nikolai Spatahri's Travels through Siberia to the Chinese Borders, publshed in St. Petersburg in 1882

The West kept referring to China as Cathay till as late as the 15th century, and was fascinated with Cathay’s unique language and customs. Similarly, Muslim geographers of the 8th and 9th century were documenting the interesting and unusual features of this immense polity. Through all of this, one thing remained consistent: China never seized to amaze the rest of the world with its wealth of fascinating features – from Ibn Battuta to Marco Polo.

You may also like: