Posted on: February 20, 2015 |

|

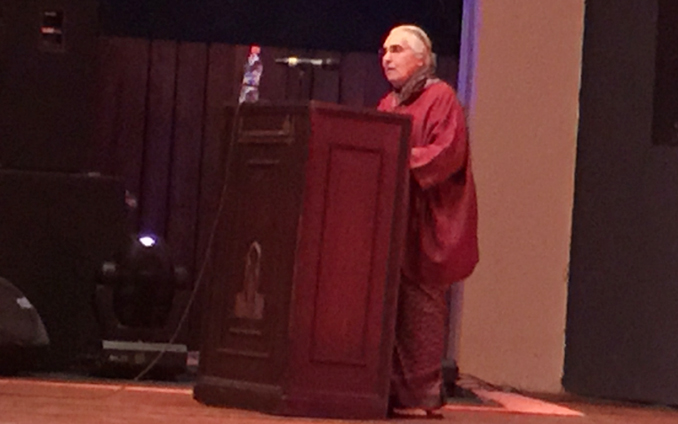

Romila Thapar |

RomilaThapar, Professor Emeriti at the Jawaharlal Nehru University, and an acclaimed authority on ancient India gave a forty-minute thought provoking Keynote Address at the Lahore Literary Festival on Friday. The intelligentsia of Lahore had braved pouring rain and waded through puddles of water to reach the Alhambra Arts Council, and hear the doyen of South Asian historians speak on “The Past as Present”.

It was a tour de force about the historiography of South Asia. She began with a quote from E.H.Carr, who had declared that history is a dialogue between the past and the present, but she qualified his statement questioning whether it is the past or an assumed past, and that “the assumptions come from the requirements of the present”. She argued that what we call our traditions and heritage are invented by us, and that while historians like to see the past on their own terms, but “our reading of it is mediated by the requirements of the present”.

While acknowledging the role of colonial scholars and their use of modern methods for recovering records, deciphering scripts, excavating ancient sites and studying ancient texts, she said that however, their interpretation of these served colonial interests and policies. She mentioned how James Mill and Max Mueller,the 19th century historians, regarded Hindus and Muslims as two nations, forced to live in the same territory of India, and how the British released the Hindus from the tyrannical rule of the Muslims. She argued that there were no such strict religious divisions or monolithic religious communities, and the religious practices of the vast majority of people were a result of the intermingling of the various religions;customary rather than religious law governed their every day lives. If a census were to be taken at the time, then the followers of the Bakhti and Sufi tradition would come out in the largest numbers.

She mentioned that her generation of historians had offered an alternate perspective, in which the religious identity of the elite classes did not matter, as the religion of the rulers did not affect the peoples’ lives. The mothers of the Mughal rulers were often Rajput Hindus, because they had to accommodate those with other religious practices. However, the text books that they had written, and had been used for four decades, were proscribed in 2005.

Her study of the temple of the Somnath that Mahmud of Ghazni was supposed to have desecrated, has been exploded as a myth in her extensive research.The history of the episode is more complex and the sources contradict each other. The process of mythologizing began with the chroniclers of Mahmud of Ghazni but was then given credence by the British, who in 1843 described the episode as a trauma for the Hindus. Mahmud’s raids were confined to one region. The citizens of Somnath were involved with Arabs in trading and they helped raise funds from the Somnath estate to help a Persian trader build a mosque there two centuries after Mahmud of Ghazni’s attack. According to Thapar, a Jain chronicler of the fourteenth century mentions that the temple was rebuilt because it had fallen into disrepair because of the neglect of its management. Akbar gave a grant to the temple in the 16th century. When the temple was excavated in 1951, it was discovered that while some sculptures had been defaced, the sea denuded others.It was the British who had started the myth that the raid was a trauma for Hindus in a Parliamentary debate in 1843. It was a historical statement that she said had been adopted by the colonial historians and later by nationalist historians. This incident of the eleventh century, she argues, has been used for legitimizing present politics.

Her message was clear and well-articulated: ideologies that led to the creation of our nation states, the time had come for their reassessment, and she argued that we must re-examine the colonial stereotypes, “that still colour our perception of who we are, what we are, and where we are going”, and maintained that “the past is being configured only for use in the present”.

|

(l-r) Shobha De, Aitzaz Ahsan, Rahul Singh and Fakir S. Aijazuddin |

The session titled “Politics, Pluralism and Khushwant Singh’s Punjab”, intended to celebrate the candor and ruthless honesty of Khushwant Singh, one of the most beloved and deeply admired partition writers. The session was steered by his son Rahul Singh, Shobha De, Aitzaz Ahsan and Basharat Qadir, with Fakir S. Aijazuddin as the moderator.

Aijazuddin inaugurated the session by describing how he brought Singh’s ashes across the Wagah border and mixed them with cement to permanently ingrain his presence in a marble plate placed outside Singh’s childhood school, the Government Boys High School. Aijazuddin wished to preserve Singh’s memory in his most beloved Hadali. The memorial plate manifests his desire in the following words: “This is where my roots are. I have nourished them with tears of nostalgia”.

Continuing this theme of love, Aitzaz Ahsan commented that Khushwant Singh’s ‘Hadali-ness’ and ‘Punjabiat’ were his most defining characteristics. He also spoke about Singh’s book, ‘Train to Pakistan’. A man who had suffered torture during Punjab’s partition authored this book and highlighted Khushwant’s constant pleas to Indira Gandhi, to release the 93,000 Pakistani prisoners of war. To this, Gandhi replied, “Khushwant, will I now have to learn humility from you?” The book brought to light Khushwant Singh’s assertion that his existence constituted of his Indian-ness, Pakistani-ness and most of all his Punjabi-ness, without each being exhibited exclusively.

As the session continued, Rahul Singh narrated his father’s enormous zest for life and his forthrightness. He explained how Khushwant Singh always referred to English as his mother tongue, despite the fact that his mother could not speak English at all. In another instance, Rahul elucidated why Kushwant was Indian; “If he had a choice, he’d be abroad, where wine tasted better and women were more forthcoming. However, despite his loathing for his country’s government, he belonged to India, to its stench, and to its nativity.”

Shobha De termed Singh an iconoclast who held the mirror to society’s hypocrisy; a Punjabi whose ‘Punjabiness’ was larger than life; a writer who wrote because he had to, until somebody would ‘invent a condom for the pen’. Most of all, he was a naïve and gullible man who, despite being wrapped around charming women’s feet, was a henpecked husband. Shobha De celebrated Singh’s irreverence and ravenous appetite for all that life had to offer, and expressed her view that while the world needs more people like him, there can never be another Khushwant Singh.

Aijazuddin, after narrating Singh’s politically incorrect, yet thoroughly amusing epitaph, concluded the session by asking his panelists where they thought they would encounter the writer’s soul: in heaven, hell, Pakistan, India or the celestial Wagah border.

Basharat Qadir, who coined the term ‘humilitarian’ for his Uncle Khushwant, recited Iqbal’s verse, which he had written on his own father’s epitaph. Rahul Singh read his father’s poem ‘Abu bin Adam’ as a response to the moderator’s question. Aitzaz Ahsan expressed that he believed he would encounter Khushwant Singh with some trepidation along the banks of Lahore canal, trying to save some trees. Shobha De envisioned Singh in “some Turkish harem or a Dublin bar, naked in every sense of the word”.

|

(l-r) Rashed Rahman, Roger Cohen, Andrew Smal, Lyse Doucet, Salil Tripathi and Laila Bokhar |

“When the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan came to an end and after martial law in Pakistan had been lifted, I went to visit the U.S. Ambassador in Islamabad and asked him what would be next for U.S.-Pakistan relations. He told me, ‘Nothing. The Soviets have gone. Now we leave.’ But then history wreaked its revenge.”

Thus began a session moderated masterfully by Lyse Doucet of the BBC. It drew on the old realist adage of there being neither permanent friends nor permanent enemies in international relations, only permanent interests. While in places the discussion broadened in theme to include snippets on emerging regional and global security concerns, a resurgent Russia, and Modi’s India, the crux of the discussion was the complex Pakistan-China-U.S. triangle in view of the regional context. Each panelist weighed in with his or her assessment on the U.S. and Chinese roles and extent of engagement in regional geopolitics.

Rashed Rahman stated at the outset that America could ill afford the luxury of leaving and forgetting about the region as it had done in 1989, in view of tremendous uncertainty as to the future: the uncertainty over the aftermath of the withdrawal of foreign forces from Afghanistan; the uncertainty about Afghanistan’s future, linked as it is to Pakistan, the region and the wider world; and the uncertainty of how U.S attempts at engaging the Taliban in dialogue, would turn out.

Roger Cohen argued that while there was no question as to the U.S. now according priority to the ISIS threat in the Middle East, it was unthinkable that it would turn its attention away from the South Asian region. The primary reasons he cited included Pakistan holding the key to any possible peaceful solution to the region, in view of how the pursuit of its own interests played out; Pakistan’s nuclear capability; the tremendous U.S. investment, in terms of treasure and human sacrifice, in the region since 9/11; and the U.S.-India.

Speaking on whether or not China was taking on a bigger role in the region, with reference to recent overtures between the Taliban and the Chinese government, Andrew Small explained the impetus China felt in engaging more actively than it had previously done, citing the foremost reason being fear of a return to the post-Soviet withdrawal conditions in Afghanistan: a return to civil war, proxy wars and a safe haven for Uyghur militants. China, he stated, was effectively utilizing its unique set of capacities and regional relationships, coupled with the increasing acceptance of its role as a regional power, to weigh in on regional affairs and create favorable conditions for its own social and economic security.

Salil Tripathi discussed Indian foreign policy engagement under Modi, highlighting Obama’s recent visit to India and what it meant for U.S.-India ties. Laila Bokhari emphasized the need for Pakistan to “put its house in order”. While she agreed that the U.S. and Europe would always stay in the region, being “dragged back in” for one reason or the other even when they would choose to exit, there was great frustration in Western governments over Pakistan’s lack of effort or lack of capacity for improving its circumstances.

While an intellectually stimulating session, it could have gone further in-depth and retained more focus, had the number of panelists been limited.

|

In conversation with Mira Hashmi and Sarmad Sultan Khoosat |

Naseeruddin Shah, legendary actor and all around brilliant human being, is enjoying a kind of a rebirth these days. Ever since he started engaging with the Faiz Foundation in Pakistan for exclusive performances and recitals to benefit the Faiz Ghar initiative, Shah’s fans on this side of the border have had the rare privilege of getting to know the “Indian” superstar in depth, and up close. Whether he is in Pakistan for a session of dastangoi, a dramatic reading of Ismat Chughtai’s short stories, or reciting the heartrending couplets from classic Urdu poetry, Shah has been rediscovered by a whole new generation, and the one before that, which is enjoying the revered thespian’s renaissance. Add to it his recently released memoirs titled “And Then One Day”, and you have the kind of fan following not even a young heartthrob can boast of these days.

It was to formally launch this very book in Pakistan that, on a wet and windy afternoon this Friday, Shah appeared on stage in Lahore yet again at the Lahore Literature Festival 2015 (LLF). Fans of all ages had strategically maneuvered throughout the day to find seats in Alhamra Hall I where the talk was to take place. Shah received thunderous applause and a standing ovation from the packed audience as soon as he appeared on stage with the talk’s moderators, Mira Hashmi (film critic and cinema historian) and Sarmad Sultan Khoosat (writer, director and actor).

At the very beginning of the talk, Shah admitted that he had no interest in looking backwards into what has gone past, but that being a part of an “immensely boring” film pushed him to negotiate through a constant cloud of boredom by writing down his thoughts and memories, which, twelve years later, were published as his memoirs. The memoir is an unabashed look at the actor’s life through his perspective, in his own words. It traverses neatly through his early life, his childhood, capturing beautiful portraits of his family life and then his hunger to become an actor, even though he repeatedly refers to as “ugly”, or a variation thereof. As Khoosat and Hashmi read their favorite lines from the book, Shah padded the incidences they talked of with his usual acerbic wit and quick responses. Since many audience members kept yelling, “Ghalib! Ghalib!” during the interview, he thanked them profusely and recounted how he will always be thankful to Gulzar for giving him the brilliantly written role, which has now immortalized him. Coincidentally, he recalled, the role had been offered to Sanjiv Kumar for a film version of the project, which never materialized. At hearing the news of Kumar’s casting, Shah apparently wrote an angry letter to Gulzar in which he brazenly lied about his familiarity with all of Ghalib’s poetry and how that role should be awarded to him Thankfully, he admitted, the letter never got to Gulzar and a decade or so later he got the part he was so passionate about.

“We still don’t know, however, if Ghalib actually looked like me at all or could sing in the voice of Jagjit Singh,” he quipped. .

On the subject of his controversial views on many highly praised films, Hashmi asked him about his stance on the cult classic “Sholay”. He candidly rubbished the claim that it is a “great” film, making many audience members gasp.

“There is not a single scene in that film that has not been plagiarized from a dozen different Hollywood films,” he stated somberly.

When asked by Hashmi as to what makes a great film, he was quick to say that any film that captures the spirit of the times it is made in is a great film, and that he has always aspired to be part of productions which remain true to this belief. As example, he offered the names of a few of his films such as Manthan and Sparsh. Talking about Sparsh, he recounted how that role challenged him to literally see the world through a blind man’s eyes, changing his perception forever about what “disability” means. The talk then veered towards the fact that many of his younger fans have inherited the sophisticated, literary version of Shah who is well-acquainted with the gems of Urdu literature, but that it was never the case in his younger days.

“Shammi Kapoor is my favorite actor. Coincidentally, he is also the person who introduced me to Faiz’s poetry,” he made the unlikely claim, going on to explain that he had seen Kapoor reciting Faiz’s couplets in a comical get-up in the film Kashmir Ki Kalli, never realizing that the poetry he loved so much came from Faiz Ahmed Faiz. “I found out much later, when my literary education finally began.” Answering Khoosat’s question, he admitted that he still believes himself to be a student of the treasures of Urdu literature and would never assume that he knew or understood it all.

From admitting the fact that he rates the “human connection and electric bond of actor and audiences” in theater far above the silver screen to telling young actors and filmmakers to never letting go of their dreams, every word Shah said was lapped up by his fans who, even after an hour long talk, were hungry for more when the talk ended. While Shah made a quick, gracious exit from the venue, those hungering for more insight into the delightful mind of the thespian must now turn to his memoirs to experience all the grit and glory of his illustrious career.

|

“For the young generation, simplified versions of my stories can be created”, Intizar Hussain responded to Kishwar Naheed’s question about the complex language used by the legendary writer. The session on Urdu’s bestseller novels and books, titled Urdu Ki Maqbool Kahanian, had Intizar Hussain, Kishwar Naheed, Nasir Abbas and Asif Farrukhi on the panel, and was attended by a large number of Urdu literature enthusiasts. Asif opened the session with his usual witty humor, explaining the reasons for the absence of Mr. Asaduddin, who was supposed to be on the panel but couldn’t make it to Pakistan.

Asif Farrukhi posed the first question to Intizar Hussain about the connotations associated with bestselling novels and their worth. In response, Hussain pointed out a strong distinction between bestsellers and popular novels, citing that Alif Laila and Akbari Asghari were not bestsellers, but popular nonetheless. Kishwar Naheed discredited the stories written by the likes of Nasim Hijazi, saying that the media had played a major role in making their stories into bestsellers. “Umera Ahmed is very popular in households today, but the quality of her work is debatable”, she articulated.

Nasir Abbas took the discussion forward, saying that the readers needed to critically evaluate their choices, because society had a very important role to play in making books bestsellers. Paying tribute to the work of Intizar Hussain, he said that Hussain didn’t revive the old era, but reclaimed it through his great pieces of writing. He also held that any piece of literature that raises questions is often hard to digest, and hence, less popular. In response to a question from the audience about the denunciation of bestselling Urdu novels by the panel, Farrukhi explained that the purpose of the session was not merely to criticize popular literature, but to deliberate and raise questions about the eminence of the work that is currently being appreciated.

The session concluded with Intizar Hussain’s amusing sense of humor, as he refused to give a message at the end, stating that, “Iqbal gave this nation a message; look what they have done to it!”

You may also like: