Written by: Jovita Alvares

Posted on: September 15, 2020 |  | 中文

| 中文

A Scene from the Hamzanama in miniature art style

Pakistan’s contemporary art scene has long been synonymous with the Mughal miniature traditions, with some of the country’s most prolific artists not only indulging in the medium but also pushing its boundaries to new and inconceivable limits. The tradition of Mughal miniature art flourished during the rule of the Mughal emperors in the Subcontinent, and drew much of its inspiration from its antecedent, Persian miniature. It began when Akbar succeeded his father Humayun’s throne, and brought with him his father’s great love for art and literature. Akbar became the greatest patron of the Mughal miniature art as he commissioned a large number of painting projects, and hired a multitude of painters to work in his court.

Originally, miniature paintings were meant serve as illustrations for texts which chronicled the lives of great emperors. The texts described ancient legends as well as recorded historical events, court life, and exotic flora and fauna for their Mughal patrons. Though greatly inspired by Persian miniature, Mughal miniature developed its own unique and recognizable style. The viewer could see the whole story occurring in the painting through a flattened perspective of landscapes. But the figures painted would be seen in a combination of perspectives, with their heads in a side-profile and their bodies displayed with a frontal perspective. Brushes, paint and wasli were all diligently made by hand and the paintings were rendered in short, fine lines in a technique known as pardakht.

Unlike other types of paintings, a Mughal miniature painting in its entirety was not created by just one person. Rather, an Ustaad (teacher) and his group of Shagird (students) would be trained in perfecting a single element of the painting in karkhanas or workshops. Once that element was completed, the painting would then be passed on to another group of specialized artists, until the work was complete. Creating a miniature Painting was a lifestyle, one that required decades of training.

The arrival of the British signaled the emergence of ‘Fine Art’ in the Subcontinent, which introduced foreign Western elements into the art form. This phenomenon brought about a shift in the way artists of the Subcontinent viewed miniatures from a craft-like, everyday art, to high art worthy of reflection and admiration. Subsequently, the Mayo School of Industrial Arts was founded in 1872, in order to encourage the mass production of various Indian art, including miniatures, which were to be exported as ‘exotic’ products to the West.

Foreign patrons soon commissioned local painters to create pieces that documented local flora, fauna and culture, slowly altering the style of the miniature pieces to include a more realistic perspective and rendering. It now focused on three-dimensionality and the use of watercolor instead of gouache. These works were termed ‘Company Paintings’, and have also influenced the contemporary miniatures that we see today.

In 1958, the Mayo School of Arts became the National College of Arts (NCA) for the newly created state of Pakistan. Although a miniature painting course had existed in the Mayo School prior to Partition, it officially became a part of the Fine Art curriculum with the establishment of the NCA. Here, Bashir Ahmed, one of the last true shagirds of the traditionalists, Ustaad Haji Mohammad Sharif and Ustaad Shaikh Shujaullah, became the last direct link between the traditional practice and the contemporary development of the medium. His dedication to the practice has inspired students for decades, and along with the establishment of the Department of miniature at NCA in 1982, became the major turning point for miniature art in Pakistan.

As the revival of miniature art continued through Bashir Ahmed and his students, it became clear that the miniature style was moving into its next phase of evolution. While adhering to the traditionalist techniques, artists began to incorporate modern imagery into their pieces. Miniature art often became satirical, reflecting on the global and political quandaries of the post-colonial world, while also integrating novel art-mediums, which was later termed ‘Neo-miniature’.

Shahzia Sikander’s prolific art practice has been a vital contribution to this revivalist movement on an international scale. A student of the miniature Department of NCA, and a recipient of the prestigious MacArthur Fellowship, Sikander took this painterly medium into the digital realm in the late 1990s. While her earlier paintings evolved from her experiences as a Muslim woman in a Western country, her style gradually developed into one which explored themes of colonization through abstract and open-ended visuals in animation-video installations.

Another to venture into the non-traditional and experimental realm of miniature art has been the work Nusra Latif Qureshi. As a neo-miniaturist, her work is concerned with articulating contemporary ideas, such as those which emerged artfully through her piece, ‘Did you Come Here to Find History?’ A digital print on transparent film, Qureshi juxtaposes her passport photographs with Mughal miniature portraits, colonial photography and Venetian paintings. The work questions the ephemeral and shifting notions of identity, in the face of large-scale historical changes.

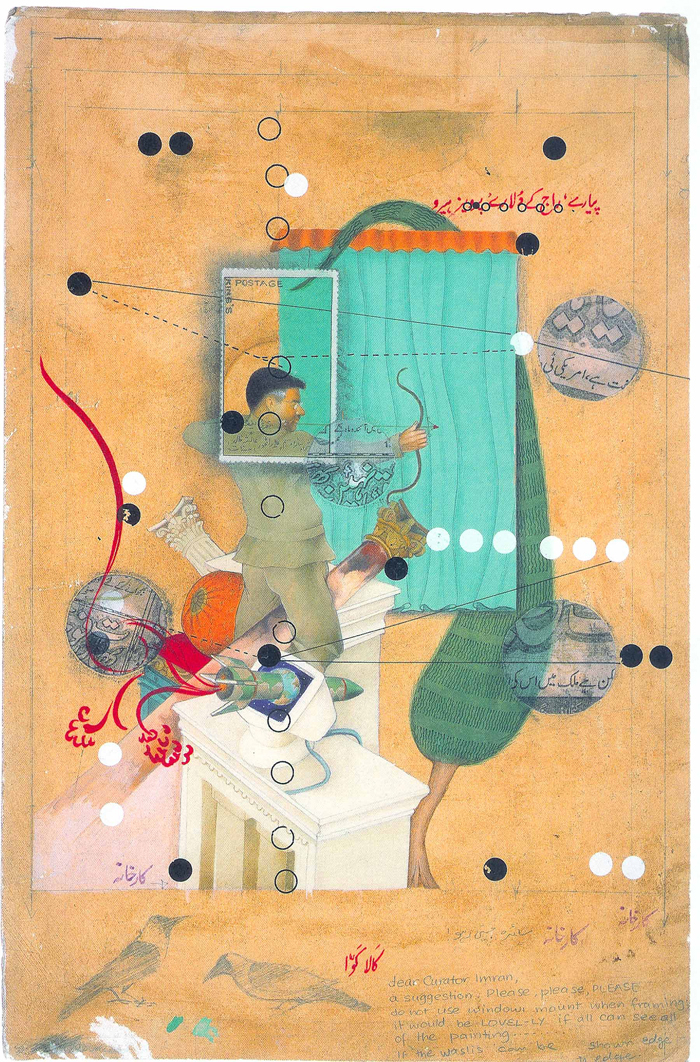

Imran Qureshi has become an appellation tantamount to the flourishing of the contemporary Miniature movement. Known for his vivid splashes and intricately painted florals, Qureshi has been at the vanguard of the international spread of Pakistani miniature art. In 2003, the artist organized ‘Karkana: A contemporary art collaboration’ in which he, along with other five artists, created a combined series of twelve paintings, which were then sent in succession to other artists via courier, each of whom applied their own layer of imagery. These pieces, once individual, now became a collaborative effort and harked back to the traditional workshops of Mughal time.

Karkhana #9 by Hasnat Mehmood, Aisha Khalid, Nusra Latif Qureshi, Saira Wasim, Talha Rathore, and Muhammad Imran Qureshi

Years later, this theme was reiterated in a live installation directed by Qureshi for the inaugural Lahore Biennale in 2018. Titled ‘Maktab’ (School), twenty-four NCA miniature graduates were invited to sit and work within an enclosed space of the Lahore Fort, which was believed to be a school during the Mughal era. The installation was meant to serve as a bridge between the past and contemporary era, through the art of the miniature painting.

Today, the style seems to be transforming yet again into it's next phase, guided by the changing shifts in technology and globalization. Artists today do not and cannot practice miniature in its pure traditional form. However, it is imperative that, in order to keep the tradition alive, Pakistani artists must find new ways of evolution and experimentation in order to keep miniature art relevant and important to the contemporary era.

You may also like: