Written by: Khadijah Rehman

Posted on: April 17, 2019 |  | 中文

| 中文

Naiza Khan, The Land Itself, 2014. Watercolour. Picture Courtesy: Goldsmiths, University of London

Naiza Khan is a multidisciplinary artist based in London and Karachi. Known for her work with personal, social and political boundaries, the artist has spent the past decade researching and responding to the Manora Island in Karachi, exploring its shifting geographical, cultural and social landscape in the form of paintings, drawings, photographs, sculptures and installations. One of the founding members of the esteemed Vasl Artist’s Association in Karachi, Khan has been announced as Pakistan’s representative artist at the 58th Venice Biennale, chosen to present a solo exhibition titled Manora Field Notes. The Pavilion of Pakistan has been curated by Zahra Khan and is being presented by Pakistan National Council of Arts and Foundation Art Divvy. We caught up with Naiza Khan and discussed her practice in detail.

On an immediate level, I guess it comes from living within an urban space, as a city like Karachi is full of a certain kind of energy and a sense of constant production. The materiality of life around me, forces me to think about my relationship to this space. I have always been interested in the built environment, and so this idea of how we construct our lives within a personal/physical space and also within the community, has been important to me.

Manora Field Notes is a project in two parts, which has been specially produced for the Pavilion of Pakistan at the 58th International Art Exhibition, La Biennale di Venezia.

The project is homage to an island space, as it benefits from the extensive research I have done over the years in Karachi. But at the same time, it moves forward, to question ideas of labour and production, optics and erasure, the ocean and its landmass.

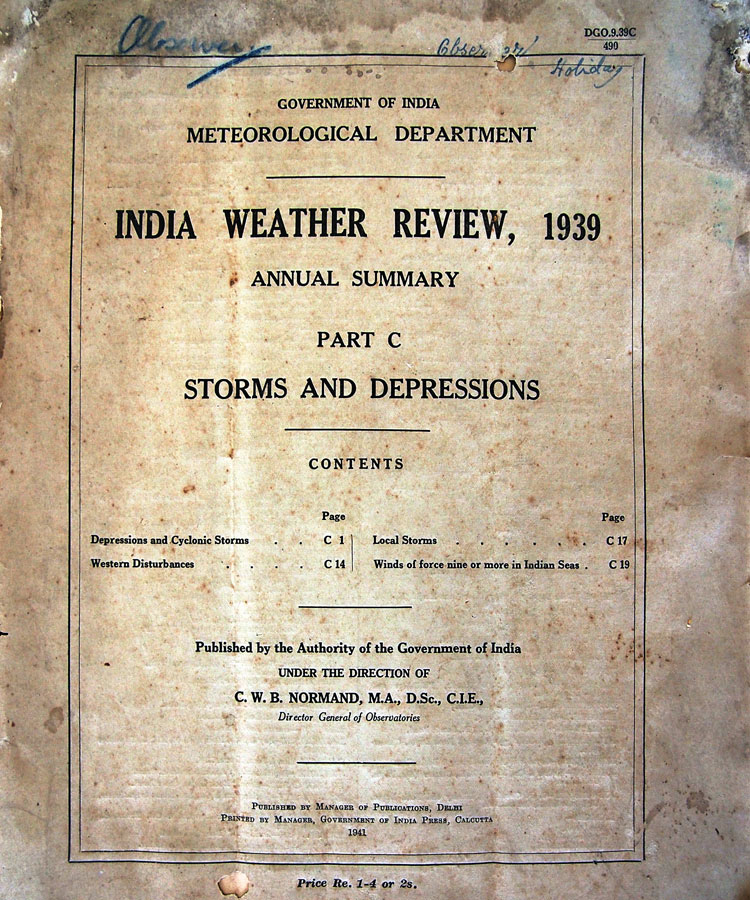

Gallery One will feature Hundreds of Birds Killed – a soundscape and installation of over 200 objects cast in brass. This sound work grows out of my encounter with the ruinous structure of the 19C Observatory on Manora Island, in which I found archival weather reports; a text that classified storms and cyclones in British India in 1939. This report of weather history offered a way to think about geography as a heterogeneous unit of assemblages; of power, colonial history and collective memory. So, I am re-constructing this archival report as a series of object-maps cast in brass.

The process of spacialising this archival document has been quite revealing, and points to the temporal and spatial markers of my project. The transformation of a lived ecological disaster from the early 20C in South Asia, a document classified through the lens of colonial weather history, a narration by a South Asian female voice, the digitalised maps extracted in multiple imaging software, with these soft files laser cut and then cast in brass through the hands of artisans in Golimar, Karachi.

This process has created circularity to these object-maps. It has also created a meta-narrative that speaks to changing geographies and the fluidity of borders.

Gallery Two will showcase a filmic installation entitled Sticky Rice and Other Stories. The work traces my journey between different artisanal workshops to produce miniaturized models of historic and contemporary boats/ vessels, which I have documented from the Karachi harbour over the last decade. The idea of scale, and maintaining the visual relationship of what scale does and what each vessel carries as its history, was important to me.

The second part of this filmic installation opens a view to another workshop, in which a vintage telescope is being cleaned and reassembled. These telescopes are low-tech constructions made with old vintage binoculars, smuggled through the border at Chaman (between Iran and the province of Balochistan in Pakistan). The conversations in these two filmic works reveal local histories, yet echo the frictions and fraught relationship between the state and stakeholders, between slow and fast technologies. I am using the lens to look at shifts of scale and friction, and accelerated processes of transformation that imply erasure.

Both Venice and Karachi are situated within historical, transnational trade routes but more interesting for me is the way that modernity and industrialization, is negotiated within these spaces. The Pakistan Pavilion is situated adjacent to the old Arsenale, an industrial assembly line, and a factory, which built warships from the 12C onwards.

Everything that happens around me is a personal concern. I don’t see these ideas of modernization and expansion as abstract ideas outside of my personal space. I think for me they grow out of the micro experience of what modernization does within our space and how we respond to it.

As an artist, I see things through a lens, which places me in a position. I don’t think this position is without empathy, and it’s aware of the criticality of seeing, the politics of looking, and the problem of aestheticizing.

I don’t consider water to have a transient nature. I think about it in relation to the solidity of landmass. I also think about its vulnerability in terms of ecological disasters and climate change. I made a small work entitled – the sea under construction- as the idea of the matter/material of the ocean fascinates me. It opens up a set of questions about how we engage with nature and how the ocean is eluding our grasp.

I would call it critical intuition! I feel both these modes of thinking are not in contradiction. My primary mode of research is visual. As a visual practitioner, I am in the field, looking and observing. So I really allow events to happen in the looking, while having a conceptual framework. These points of critical observation are translated through drawings, prints, photographs and the moving image. The observation does not only relay things that I am witnessing, but also emotions, responses and exchanges with people. For me, as an artist, the stimuli that take place ‘in the field’ are really multiple and complex. The first contact with a situation or a place is critical for me, and so I try to open myself to these moments, which are often ephemeral.

Working intuitively and with a sense of freedom is really why I am an artist. My textual research and conversations is part of my creative practice. The observation/ drawing work also guides me towards the theoretical research that I need to undertake in order to understand the historical and critical contexts that are out there.

As an art practitioner, I am not working in isolation; visual practice is in conversation with other forms of learning/ disciplines and everything that we experience in our lives.

Yes, absolutely. As a woman, I am constantly negotiating the public space that is highly gendered. The situations I encounter feed into my work in different ways.

Recently, I have been working in Golimar to produce the brass maps and objects that will be seen in the Pakistan Pavilion. This area is a labyrinth of small lanes with many copper and brass workshops, casters and welders. These artisanal communities do not have any women working in them, nor do you see women without a chador in that space. So, for me to be there on the street, working with them is quite unusual.

I am also aware that it’s quite tough for the men around me to feel comfortable and at ease when they work with me. I try to be mindful of their space and also of the customs that are close to them. It has taken me a long time to build up the trust and level of comfort to let them give me access to their space. I feel they also appreciate the fact that I am very hands on and working alongside them. There is also a process of learning here, which runs both ways.

I am working closely with a sound engineer to create a soundscape of the archival weather report. I felt the uncomfortable closeness to the idea of climate disaster, and how we are not able to comprehend the scale of impact or speed of the changes around us.

Naiza Khan’s sensitive musings and explorations as an artist are significant at a time when urban development and modernisation are swiftly transforming the local landscape. In collaborating with the artisanal community of Karachi and holding an intense dialogue with its members, she has crafted an empathic art practice that is more than worthy of the recognition and admiration it has amassed around the world.

The Pavilion of Pakistan is on view from May 11 to Nov. 24 at Tanarte and Spazio Tana, Castello, Venice.

All pictures provided by the artist, unless mentioned otherwise.

You may also like: