Written by: Mahnoor Fatima

Posted on: May 27, 2021 |

(L to R) Alexander Pushkin, Maxim Gorky, Anton Chekov and Leo Tolstoy

Russian Literature is known and celebrated around the world for its complexity and stories, with authors like Leo Tolstoy, Anton Chekov and Maxim Gorky translated into several languages around the world. Russian Literature has also a long and extensive part in the cultivation of Urdu Literature in terms of structure and themes. Their similarity and mutual complexity make both traditions well placed for cultural and literary exchange that continues today.

Historically, the impact of the events in Imperialist Russia and the Soviet Union, and the literary response towards these events had massive reverberations in countries where colonialism remained in place. The rigid and stagnant social and political milieu which the Russian middle class and intellectuals often expressed through writing.

However, it’s within Urdu literature that the Russian style truly blossomed, especially in the short story format. This is largely attributed to the works of Chekov who broadened the horizons of the short story, and Gorky who introduced progressive elements and social critique within literature.

Even before the events of both the Russian Revolution and the Indian independence struggle, key figures like Gandhi and Rabindranath Tagore were heavily influenced by Pushkin and Tolstoy, who critiqued the classist elements of their society and the wealth disparity between people. The works of Gorgy, Nikolai Gogol and Chekov were already popular in Indian literary circles by the turn of the century.

But it was the events of 1917 which deeply influenced the way Urdu writers would think about their language and their identity in the face of great international change. It inspired the likes of Allama Iqbal to incorporate ideas of a revolution that would bring dignity to mankind and inspire ‘Khudi’ (Selfhood).

The image of a revolutionary ‘spark’, popularized by Lenin’s revolutionary underground newspaper Iskra (which means ‘spark’ in Russian), is still one that frequently features in many of Iqbal’s writing, and many literary experts see the influences of the revolution’s ideals in his poetry.

What can I do, my Lord

My heart is restless.

When my eye sees a thing of beauty,

My heart hungers for something more beautiful,

Like a breeze in the poppy-field,

I pass from petal to petal

And plant to plant.

From the spark to the star

And the star to the sun

Is the range of my quest.

I, therefore, seek the end

Of that which is endless.

Urdu’s foremost short story writer Premchand was heavily influenced by the revolution, and his work turned peasants and workers into the protagonists of stories asking for social justice. Famed Urdu writer Saadat Hassan Manto translated the works of Tolstoy and Gorky early on in his career, and their works inspired him to pen the miseries of human existence in graphic form in his own language.

But it was the establishment of the Urdu Progressive Writer’s Association (PWA) in 1940 that truly allowed Russian works and themes to flourish within intellectual Urdu Society. The group was formed by some of Indian literature’s most talented minds, seeking to inspire people through writings that advocated equality and attacked anti-imperial, class-based injustice.

Alongside this, Urdu literary magazines all over India popularized Russian literature in Indian households by frequently publishing translated short stories. At the time, modernist ideas that involved Surrealism, Existentialism, Marxism and Impressionism helped bring complexity into Urdu writing and storytelling.

And no other Urdu writer is a better representation of a bridge between both cultures than Faiz Ahmed Faiz. With his soft voice and unrestrained emotional expression tinged with streaks of melancholy, Faiz’s work characteristically displays Chekovian sensibilities. Faiz was one of the founding members of PWA and recipient of the Lenin Peace Prize in 1962, his work dealt with the struggle for emancipation within their unique colonial context.

Comparing Faiz with Iqbal, translator Victor Kiernan perhaps best summed up Faiz’s hope and longing for revolution. “At his most natural Iqbal is ardent, impetuous, direct; Faiz more delicately suggestive and even less easily translated. One paints a picture that seems bathed in sunlight, the other in moonlight. Iqbal's pan-Islamic thinking brought to his mind memories of the Muslim as a world-conquerer; Faiz was concerned with the Muslim of his own times, as an under-dog in some manner was able to fuse sympathy for the hard-pressed labourer or peasant with the traditional grief of the lover."

Dr. Ludmilla Vasilieva is one of the foremost authorities of Russian to Urdu translation, having translated the likes of Iqbal and Faiz from Urdu to Russian. She was also a personal friend of Faiz and served as his interpreter in Moscow between 1967 and 1984.

(L to R) Sajjad Zaheer, Ludmilla Vasilieva and Faiz Ahmed Faiz at the Alma Ata Writer's Conference, 1973

At the book launch of Faiz’s autobiography ‘Parvarish-i-Lauh-o-Qalam: Faiz: Hayat aur Takhleeqat’, Dr. Vasilieva explained that Faiz’s sadness and disillusionment of socialist ideals did not just come from intense repression by state authorities but also from the negative aspects of life in the Soviet Union.

Today, production houses like Maktaba-e-Danyal continue a long tradition of translating works of Russian into Urdu. Maktaba-e-Danyal has been operating since 1967, and its current owner Hoori Noorani translated Russian stories like ‘Interview in Buenos Aires’ by Genrik Borovik, which she also performed with the Dastak Theatre Group during the Zia era of repression and censorship. In an interview, she explained, “I thought it was very relevant to Pakistan’s situation in the ’80s. I don’t know how it passed the censors at the time, but I don’t think they understood it.”

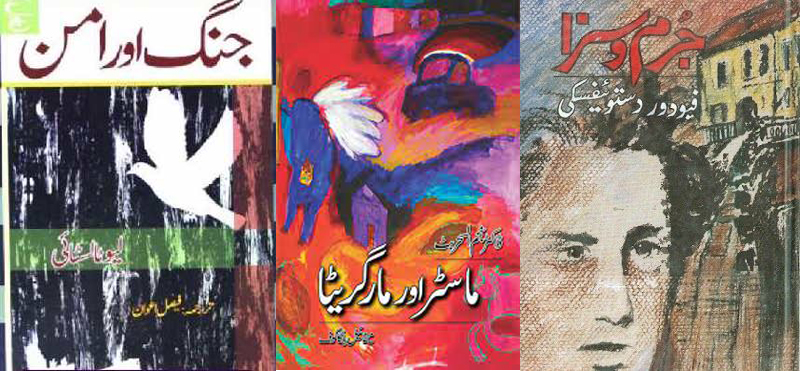

(L to R) War and Peace by Leo Tolstoy, Master and Margarita by Mikhail Bulgakov, and Crime and Punishment by Fyodor Dostoevsky

But the biggest problem for translations of Russian into Urdu is not that of state repression or curtailment. It is one which many non-English translations face: many of the translators of non-English literature consult poorly translated English versions to write the Urdu books. Within the degrees of separation, much of the content and context is lost and the full impact of the words remain unclear to the reader.

Those who have translated Urdu to Russian and vice versa have remarked that, compared to English, Urdu is much better equipped to translate into Russian. During an event hosted by literary group ‘Joy of Urdu’, Dr. Vasilieva explained how Urdu and Russian have been in-tune with each other on multiple structural levels.

Just like Urdu is the amalgamation of Persian, Turkic and Arabic languages, so too is Russian a collection of other languages like Slavic, Germanic and Dutch. Dr. Vasilieva and many others believe that the rich complexity of Urdu’s vocabulary, followed by its natural musical cadence, allows it to be much better placed to truly capture and match the complexities of Russian. For translators, it is not as important to translate word-for-word, as it is to capture the essence of the culture and traditions within it.

Urdu’s extensive literary history, sophisticated structure and poetic vocabulary has allowed it to bring complex Russian ideas about humanity and society into local intellectual circles. Moreover, the historical developments in Russia and the Soviet Union has greatly impacted the trajectory of progressive Urdu literature as it grappled with the post-colonial world, and the aim to bring about emancipation through intellectual struggle.

You may also like: