Written by: Ilhan Niaz

Posted on: October 14, 2014 |  | 中文

| 中文

Muhammad Mujeeb Afzal. Bharatiya Janata Party and the Indian Muslims. Karachi: Oxford University Press, 2014. Pages: xxx + 451. Hardback. Price: PKR 995. ISBN: 978-0-19-906997-2.

Muhammad Mujeeb Afzal’s Bharatiya Janata Party and the Indian Muslims is a groundbreaking academic study of India by a Pakistan-based scholar. The study examines the complex and fraught relationship between Hindu nationalism and the Indian Muslim minority as well as the implication of the former’s rise for the Indian polity. There is much to recommend this study but three aspects of Afzal’s effort merit special mention. First, Afzal explains in detail and without emotion the logic of Hindu nationalism as it continues its rise to preeminence in Indian politics. Second, the role of the Indian National Congress (INC) in creating space for Hindu nationalism is dissected. Third, the limitations and dangers of Hindu nationalism for India are brought out especially with reference to the alienation of India’s Muslims from the mainstream.

Turning to the first outstanding lesson of the Bharitya Janata Party and the Indian Muslims, Afzal’s effort confronts the general ignorance about India that prevails in Pakistan. While Pakistan is full of ‘experts’ on India fond of making ex cathedra statements, there is practically no meaningful attempt to understand the psychological and historical conditioning of the ‘other’. Afzal deserves to be catapulted to national fame on account of this book. What he has to say in the substance of the book and the knowledge and perspective it contains about Hindu nationalism, Muslim nationalism, and contemporary South Asia are sobering and engaging.

The essential long-term aim of the BJP project is to restore India to an imagined glorious past in which true Hinduism, free from caste distinctions and other impure accretions, prevailed. This authentic archaic utopia was lost on account of foreign invasions of India and the spread of anti-Indian ideologies by Turco-Persian Islamic imperialists and the British. From this perspective the only truly secular and national Indian identity was Hinduism and those belonging to other religions were subject to the cultural and spiritual norms associated with being Hindu. The INC, from this perspective, was (and is) a cynical, pseudo-secularist party that maneuvered with the Muslim minority and self-loathing liberal Hindus to keep its vote bank above the critical 30% threshold needed to win in national elections. Against these panderers, opportunists, and cynics were ranged the Hindu nationalists organized in a family – the Sangh Parivar. The BJP was the political front organization for the militant socio-religious movements of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) and Vishwa Hindu Prashad (VHP). This functional division provides the BJP with greater tactical flexibility, which, the Hindu nationalists gradually realized over many elections, was essential to capturing power. It also means that once in power the overtly religious members of the family can exert significant influence on the direction of government policy.

|

"The essential long-term aim of the BJP project is to restore India to an imagined glorious past" |

Turning to the Congress, which governed India almost continuously (with only one interruption, 1977-79) from 1947 to 1996, Afzal analyzes the phenomenon of failure on part of secular-liberal elites to deliver on the promise of independence. In Pakistan democratic apologists point out that instability in the political system and regular military interventions stopped the political class from delivering. This naïve hypothesis falls apart when the Congress’s abysmal track record on economic development, provision of substantive rights, and governance, is placed side-by-side with its stunning success in holding on to power. Rarely in modern history have a few thousand politicians from one party misruled so many for so long without producing a breakdown of the constitutional order.

From the BJP’s perspective, the Congress’s adeptness at staying in power was itself reflective of a deep rot in the soul of India. Congress managed to keep the minorities, lower castes, and other backward classes, convinced that only it could keep secularism going. Within the minorities the Muslims assumed special significance on account of their overall strength and demographic distribution, which proved key in a substantial number of districts under India’s First-Past-The-Post (FPTP) electoral system. This accommodation was characterized by a bargain between the Congress and the Indian Muslim leadership that allowed traditional and semi-feudal remnants to assume leadership over Muslim India in exchange for not moving forward with the promulgation of a uniform civil code and avoiding incorporation of Hinduism in the mainstream educational system, while allowing Muslims some autonomy in running their own charities and deeni madaris. The dominance of the liberal elite in the bureaucracy and professions, at least for the first generation after 1947, also kept the Hindu nationalists out of the corridors of power.

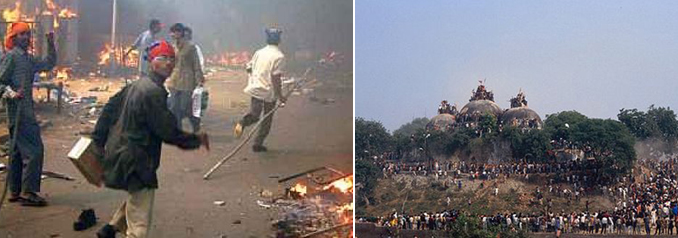

To counter the Congress, the BJP and its allies sought to build a cohesive Hindu voting block that would respond to cultural and religious symbols, such as demolition of the Babri Masjid and construction of a Ram Mandir in its place, while projecting itself as a party of discipline and principles that would work for the real welfare of India’s masses rather than making deals to stay in power for its own sake (or that of the Nehru-Gandhi dynasty). Here the BJP eventually succeeded on account of its own persistence and the Congress’s protracted failure to deliver. The real opening came when the Congress, faced with an economy headed towards collapse, started toying with reform in the mid-1980s before making a more serious attempt in the early-1990s. Allying with regional parties, the BJP was able to steadily increase its share of the vote so that by 1998 it was able to become the dominant coalition partner at the center.

|

Gujrat riots Babri Masjid |

Back in 2006, in An Inquiry into the Culture of Power of the Subcontinent, this reviewer made the case that the BJP’s vision of a Hindu Rashtra was consistent with India’s historical experience of governance and likely to prevail in the long-term. Congress, having abandoned its (poorly implemented) redistributive mission in the early-1990s had lost its ideological legitimacy and the transparent decay of Indian state institutions and writ meant that managing liberalization, especially the inevitable sharp rise in inequality, was likely to prove beyond the ability of the old regime. The groups likely to benefit from these policies were, in turn, unlikely to support a party long identified with a status quo that attempted (with great success) to freeze Indian socio-political development at a 1960 level. Narendra Modi’s rise to the premiership, prior Gujarat massacre notwithstanding, and the BJP’s formation of a majority government in 2014 are both logical outcomes of India’s reversion to pre-British norms of exercising power and reflect the real emotive resonance of India’s Hindu culture and religion. Afzal’s view is rather different and argues that the BJP faces enormous difficulties in forming governments, as well as in staying in them, on account of the divisiveness of its ideology and political program. Pursued aggressively, the Sangh Parivar program would risk the radicalization of India’s minorities, especially the Muslims, and possibly lead to other unwholesome consequences such as liberal and secular forces uniting to resist revision of curricula and dilution of official secularism. Whatever one’s take, the BJP’s rise has clearly not hit a plateau and poses some challenges for Afzal’s analysis and framework.

Overall, Afzal’s Bharatiya Janata Party and the Indian Muslims is a fine book and ought to be widely read in Pakistan. Indeed, it ought to be compulsory reading for Pakistani diplomats and military officers and it represents a refreshing addition in terms of variety to the scholarship being produced in Pakistan. One hopes that Afzal will continue to write about India and, in doing so, add desperately needed depth to the Pakistani understanding of its neighbor.

You may also like: