Written by: Mina Sohail

Posted on: July 23, 2014 |

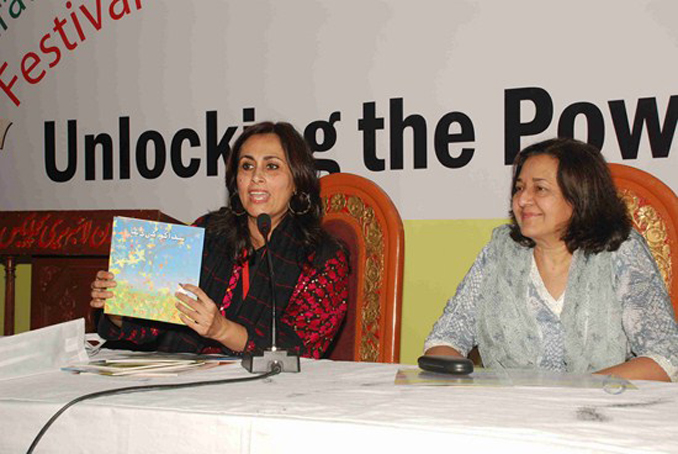

Fauzia and Samar Minallah

Samar Minallah is an anthropologist, filmmaker, and renowned activist who has worked on issues such as human trafficking and those relating to women and children. In a casual tete a tete with Youlin, she discussed Pakistan’s culture, heritage and campaigning on social media. Fauzia Minallah artist, painter and founder of Funkor Child Art Center, believes in using the medium of art and books to promote peace and tolerance among children. She talks to Youlin about inspiration for her work from the ancient cemeteries in her parents’ hometown of Sirikot, Hazara to the Banyan trees of Islamabad.

The fact that they celebrated the day was a positive change. In Pakistan we tend to ignore the importance of culture and cultural diversity. For me it was an opportunity to show a shorter version of the documentary and talk about why I feel culture needs to celebrated in Pakistan and how exactly it is linked to many issues like peace and development.

|

Filming in Rahimyar Khan for a documentary on Human Trafficking |

When I started studying at Quaid-e-Azam University, I had no idea how interesting anthropology could be. Then I went on to do my Mphil from Cambridge University and there I was introduced to ethnography. A link between anthropology and development, it was something I found relevant to Pakistan; I was extremely inspired by this particular genre. Before getting into documentary making, I worked as a freelance journalist. My first documentary was in Pashto. In 2003 no one was interested in seeing documentaries in Pashto; nevertheless, I got a great response. My first documentary was on a custom called Swara, where minor girls are given to enemies families. It is an anthropological issue but I had to raise awareness from a human rights angle. It was a challenge as I wanted general audiences to relate to it and not see it as propaganda against a culture; it had to be culturally sensitive. The kind of reviews I got the next day in the papers made me feel this is what I should pursue.

|

With young girls from Kalaash |

At times, one does get discouraged but I’m positive that things will change one day. Like the custom of Satti in India no longer exists. It just takes a very long time for people to realize certain customs are violations. Initially people I talked to in rural areas considered Vani a part of their culture and would talk about how positively it impacts their society because the girl sacrifices for the larger good. Now in rural areas you won’t find many people giving this argument. It is frustrating because it is slow and gradual but one has to continue advocating against it in a very culturally sensitive way.

There are hardly any events here. If you go to a local school here and ask teenagers, they wouldn’t be able to differentiate between Punjabi culture and Kalaash culture. I did a project as a consultant with UNESCO, where a kit was developed for government schools with documentaries and reading material. The aim was to familiarize school kids with our rich cultural diversity. It is almost considered uncool for people to show interest in our heritage. Coke Studio was a good effort in that sense; it packaged music in a way that appealed to the younger generation.

Yes, peace and culture are interlinked. We don’t see many people practicing their traditional folk music like in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. Music is something that brings people together, irrespective of caste or religion. If we discourage these musicians, they get agitated and there’s a big chance they’ll find other means to take out frustration like violence. Also, our tourism industry is in shambles. If the government, people and the development sector realize how important this link is to development or peace, they’ll think of investing more.

Our archaeological sites are all in pretty bad shape. In Pakistan, we have around 7 sites designated heritage sites by UNESCO. Ideally we should have tourists coming in but we haven’t been able to sell this aspect. Tourism also gives people a chance to earn money so employment is another positive side to promoting it. Like crafts, traditional embroidery etc., that in itself has a strong link to development, if linked to a market economy.

You were actively Tweeting about the honour killing incident outside the Lahore High Court. How does social media help advance such campaigns?

Social media does help but it is catering to a specific audience. My background is in communication so I believe you have to reach out to different audiences through different means. Twitter, Facebook and other platforms are for a specific audience. I usually like to reach out to communities in rural areas.

In 2004, post 9/11, I was living in Peshawar. I would come across these Afghan women who were coming to Peshawar hospitals as victims. I felt no one would give any media attention to them because this is not a story that would sell or an international channel would be interested in. So I picked up my camera and interviewed them because I felt their voices should be amplified. There were some foreigners working for Afghan refugee women in Austria and invited me to Vienna to show the documentary to exactly where the voices needed to be heard like the UNHCR. That was very encouraging.

Do you find it difficult to interview villagers for your documentaries?

Getting villagers on screen is a big challenge but you have to be very honest with them and tell them what the purpose is and where it would be shown. 2 out of 10 people would let me film. Mostly, children or women who have survived some violence are more interested in sharing experiences. Women in the process of being victims to violence are more hesitant.

Swara advocacy is part of my life, so work on that continues. I will be going to Sukkhur in the coming days to talk to the law enforcement agencies there and sensitize them about the laws on compensation marriage. Last month I recorded a folk song in Peshawar in a well known studio. We had traditional folk musicians taking part and I’m making the video for this song, shot in Peshawar and Islamabad.

Being on the board of directors for the children’s literature festival allows me to interact with a lot of children. I believe that instead of lecturing children, showing them a short animation can be more effective. I created a cartoon character Amai, who promotes values that enable children to be responsible citizens. It’s an animation with music only. Through her, I give children messages of tolerating people who are different and then ask them to tell me about it. Through these images, they start thinking.

|

At the Lahore Children's Literature Festival (2011) with Ameena Saiyid (r) |

It’s a difficult task in Pakistan. The need for peace and tolerance is because we have become a society over the years that took about three decades of social engineering where the Pakistani child is taught that to be Muslim is most important. I went to some government schools where I told them I want to tell the story of Mohenjodaro to children. The teacher asked me why as they did not teach that. We have to now think about methods and ways in which we can inculcate a civic sense in kids. It is important for Pakistan because we are becoming a very intolerant society and a lot has to do with the syllabus that is taught. Everything has to do with religion now and little to do with what kind of human they should be.

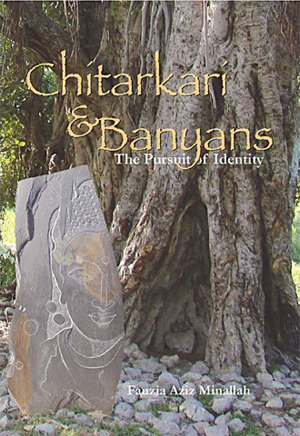

I am from Sirikot and we go to our village often. I compiled a book called Chitarkari and Banyans - The Pursuit of Identity, which took me three years to put together. By documenting this whole book, it became part of my identity. For me, Islamabad is nothing without its trees. It is the only city where the archaeology department has not preserved a single heritage site.

In the 90s when I returned from the United States, I would go to my village and document tombstones in cemeteries. My mother and I then promoted this work of slate engraving exclusive to Sirikot through media, including through a show on PTV with my mother. When the village people saw that show, they were amused that these women were so impressed by something they had almost given up. Tombstones show a whole story about the person. One had a prayer mat engraved on it, which showed how religious the person was. In another graveyard there was a piece of necklace and earrings on the tombstone that symbolized a beautiful young, woman. Some that have no writings on them are probably around 500 years old. Those with dates on them are 200 years old.

|

Craftsmen in the village pass it on to their children because there is still demand for it. Some of them have even moved to Islamabad and sell it at quite expensive prices, and it is a major source of income for many families. The symbol of identity is so unique to people in Sirikot. However, as people are becoming more conservative, they are frowning upon musical symbols. Religious ones like mosques and prayer mats are more acceptable now.

The construction going on here is so frustrating. The World Bank was giving an option other than the metro bus. Over here, just a few people start deciding what to do. The whole city is at a standstill. I was part of the protests in 2005 when they started the beautification of Islamabad. They cut down thousands of trees including a banyan tree in Bari Imam, which has now been destroyed and a mosque has been built there. This is how cities change, not just with aesthetics. The destruction of our heritage is because of radicalization also. There is graffiti by religious groups on walls in many sites of heritage significance that should be preserved well.

In my animation Amai, she meets Hindu children, celebrates holi, paints a picture with Sikh children and celebrates Christmas. She teaches children about interfaith harmony. The education system here is such that it gives a very exclusionary worldview to a child. It is not very inclusive of other cultures and religions.

The views expressed in this article are those of the interviewee and do not represent the views of Youlin.

You may also like: