Written by: Syed Abbas Hussain

Posted on: October 03, 2016 |  | 中文

| 中文

Ahsan Khan's brilliant portrayal of a pedophile

With Udaari's outspoken portrayal, the issue of child abuse is finally out of the closet; it is a topic that can no longer be hidden behind stoic faces and disapproving eyes.

A television play that has become a topic of discussion across the country owing to its contentious theme, Udaari truly has left a resounding impact. This is by no means a quintessential television serial with a sappy romance or an extramarital affair as its plot hook. Nor are its protagonists bejeweled conspiratorial women caught in a love triangle. Udaari is stuff that thought-provoking art films are made of. Its jarring content often leaves you shell shocked and uncomfortable to the core. It is not always the visual imagery that evokes the visceral reactions; the grotesqueness lies in the unspoken words, the subliminal messages, and the gut wrenching moments that gnaw at your insides. Moreover, with a dash of humour and a tight screenplay, it manages to grip the viewer’s attention without becoming overbearing. KASHF Foundation in collaboration with Momina Duraid (MD) productions of Hum TV has produced this path-breaking TV serial that highlights the issues of child abuse and gender empowerment.

Television dramas, as opposed to films, are more conservative in terms of the issues that they touch upon, given that families predominantly constitute their target audience. Udaari on the other hand, pushes boundaries of what has traditionally been considered “permissible viewing” for Pakistani television. It was hitherto perhaps unthinkable for terms such as ‘pedophilia’ and ‘child rape’ to be used in television drama, and there were certainly consequences to Udaari’s shattering of conventional sensibilities. Complaints from a certain section of viewers translated into a showcase notice issued by PEMRA. However, better sense soon prevailed, and a social media backlash led to PEMRA rescinding its decision.

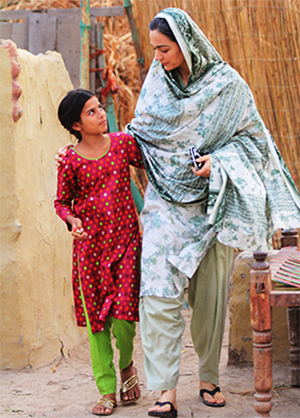

The story of Udaari begins in the dusty plains of interior Punjab in a decrepit but bustling village, with the introduction of two families, who are next-door neighbours. They live in humble mud houses lined with low-lying boundary walls bathed in pastel colours, and open courtyards resonating with the sound of birds chirping. They draw water out of wells with hens fluttering around, and start their day with a simple meal of roti smothered in desi ghee, cooked over a log fire on an earthen stove. One of the families is headed by a lady called Sajida who is endearingly referred to as Sajjo (played by Samia Mumtaz), a widow who works as a cook for a well-to-do family in the city and looks after her 10-year-old daughter Zebo. In the house across them resides a family of musicians who, like Sajjo, struggle to make ends meet. Their day to day struggle is shown through simple, yet powerful interactions, such as when a child complains to his elder sister about consuming milk as a substitute to his meals, as there are times when the family can’t afford to purchase food items. However, the portrayal of their poverty doesn’t end up becoming a morbid tale of tragedy that is chronicled through a morose sounding orchestra as background music. The characters are resilient, many of them strong women who face the perils of life head-on. Bushra Ansari as Sheedan is a feisty singer and a matriarch of her family, who in spite of the social stigma that hounds her Miraasi family is fiercely proud of her roots and considers herself a hardworking professional. Her daughter Meera is played by Urwa Hocane.

The village setting is contrasted with Lahore’s urban ambience, marked by exquisitely furnished upper middle class homes, laid out with embroidered carpets on glinting marbled flooring and neatly manicured lawns. A young group of college students, who play music as an amateurish band and harbour aspirations of becoming overnight celebrities, carry the story forward in the subplot. Farhan Saeed, from the famous band Jal, plays the brooding and spoilt Arsh. The sub-narratives are entwined beautifully before a scathing tension in the plot is brought in by the character of Ahsan Khan, which forms the cornerstone of Udaari’s storyline.

The strength of Udaari’s writing and direction lies in its ability to depict the lives of its characters with realism. With a majority of Pakistani television showing myopic characters placed into stereotypically demarcated slots, Udaari stands out for having a narrative endowed with depth and nuance. It is refreshing to see poor people in a village shown to not lead a life of abject misery and oppressive patriarchy, and city dwellers not being showcased as emblems of debauchery. For instance, the NGO worker in Lahore enacted by Laila Zuberi, contrary to the evil Fareeda from the popular serial Humsafar, is genuinely compassionate and works for the emancipation of the underprivileged. Writer Farhat Ishtiaq, after penning some of the most commercial plays, has delved into a totally different genre and in the process, delivered a masterstroke. Mohammed Ehteshamuddin on his part deserves praise for directing this ambitious project with finesse, as well as fleshing out the sensitive story in an impactful and engaging manner.

Udaari’s cast members deliver commendable performances, completely sinking their teeth into their complex characters. Particularly noteworthy is the fact that all of them perfectly capture the village dialect and maintain it flawlessly throughout their scenes. Samia Mumtaz shows an intense and gritty side in the latter episodes, exposing her formidable talent – the kind that is seen in her theatre performances. The legendary Bushra Ansari is a chameleon who can embody any character with ease. Udaari is yet another feather in her cap. With her Kohl-smudged eyes, candy coloured laacha, chunky earrings and coarse tone, she is every bit of her character. Urwa Hocane and Farhan, too, are supremely natural, and emote with a tactful restraint. Areesha Ahsan and Hina Altaf as the young and older Zebo show adeptness at their craft, and tug at the heart’s strings as they embody the painful journey of a child who has been violated. The person who steals the show, however, is Ahsan Khan. He transitions comfortably from a visibly benign, immaculately dressed man into probably the most hateful character to have ever graced television screens in the country. His lecherous stare while biting onto his golden chain, the twitch on his face, his menacing gait and voice modulation, all result in a chilling effect. He has an overpowering presence that allows him to deliver the performance of a lifetime.

Udaari raises some very important issues, such as victim shaming in the context of rape. In a memorable sequence, the rape victim is emphatically told, “You have no reason to feel embarrassed or ashamed. It is the rapist who ought to be ashamed and not you. You are a survivor, not a victim!” This message effectively captures the core problem that relates to pedophilia. Much like the pedophile, a victim’s family and the society as a whole, generally shames victims into silence, thereby allowing the perpetrator to roam scot free and emboldened to commit the heinous act again.

There was one questionable instance in the play, though. In reference to the rape victim, it is said, “Uskee izzat loot lee gayee’’ (She was robbed of her honour) – a statement that is not contested later. The idea that rape or molestation can purge a person of his or her dignity stands in contradiction to the ethos of the serial.

It wouldn’t be an overstatement to say that Udaari is a groundbreaking television play, for it has dared to bring the topic of pedophilia to mainstream television. While the play has come to an end, its powerful message will resonate with the audience for a long time, and hopefully alter public discourse in Pakistan around child abuse.

You may also like: