Written by: Aiza Azam

Posted on: May 21, 2014 |

Sarmad Tariq and Zehra Kamal

“He never thought he was capable of it. But when the time came he overcame all the obstacles. He never thought he was capable. But when the opportunity came he grasped it with both hands. He never thought he was capable. But when he came face to face with challenges, he was up to the task every single time. He never gave up. He never gave in. He kept moving forward. He kept falling. But he kept getting up again. And he kept moving. He never thought he was capable. But, more importantly, he never thought he was incapable either. Maybe the secret lies in not thinking what you can or cannot do. Maybe the secret lies in just doing it and finding out.”

Sarmad Tariq was an exceptional human being.

In the days since his passing, many previously unacquainted people have come to know, first, of him, through the wide outpouring of tribute by those whose lives he touched; and then about him, not just from people he knew, but directly in his own words. His writings are a legacy that are enabling more people every day to hear him, a man who allowed tragedy to dictate his life in a most unconventional way: by living it.

Sarmad’s story and his achievements – as an athlete, as a motivational speaker and as a writer - have been well documented. An aspiring boxer at 15 years of age, he fell victim to an accident that left him paralyzed from the shoulder down. Months of medical complications and treatment had to be borne by him and his family, on top of the new reality that he would never stand, never walk, never run again. Devastating knowledge of this nature, the seeming affirmation of a life of limitation and dependence, could have beaten Sarmad down; but he rejected it. What followed was a series of uphill battles, from pursuing higher education to learning to drive a specifically modified car. Alongside mastering personal challenges, Sarmad had to learn to mollify and overcome the well meant fears and unconsciously adverse advice of the people who loved him and did not want to see him hurt.

“The silent message being sent to me unwittingly by my well wishing friends and family had been to accept my state and transform myself into a ‘happy vegetable’ content with my existence, starved of all challenges and achievements. Everyone almost had me convinced that the only thing worth concentrating was on trying to walk again, and not on walking tall.”

|

The NYC Marathon in 2005 |

Sarmad, however, would not be cowed down by pessimism and refused to acknowledge the word ‘impossible’. He earned an MBA degree, landed a job and, in his early 20s, married the woman he fell in love with.

Zehra Kamal, Sarmad’s wife, is a practicing clinical psychologist; she also works in the development sector, with expertise in gender violence and youth issues. Her and Sarmad’s fathers were in the army and their families were neighbors when they lived in Quetta. This was before Sarmad’s accident. Some years and several army postings later, a conversation with a mutual friend led Zehra to reconnect with him. It took them less than a year to realize that they wanted to marry. Both had their concerns owing to the particular circumstances they would face, but the concerns were with respect to the comfort and ease of each other. They did not need long to make their decision, though, and welcomed the support of both their families.

For Zehra, the thirteen years she and Sarmad were together was a time of tremendous growth. “We got married young, and we both saw each other mature over time, both personally and professionally. We both grew together as a couple, but being distinct personalities with independent pursuits, we made our own decisions.”

In her experience, few spouses can be as supportive as Sarmad was of her. “He was free of any hang-ups and insecurities. He always took great pride in all my achievements and, unlike so many men in a society like ours, he never held me back nor limited me in what I could and couldn’t do, always encouraging me to excel in everything I did and loved. I was frequently reminded of how grateful I was I’d married him, how lucky I was.” Once, he was due to leave for the UK for treatment and it coincided with a trip Zehra was to undertake for work to Afghanistan. Both were set with everything planned out, until, three days before Sarmad was due to leave, his blood pressure dropped low enough that he lost consciousness and had to be rushed to the hospital. He woke up 16 hours later and the first thing he asked Zehra when he saw her was, “Why didn’t you leave for Afghanistan? I made you promise!”

|

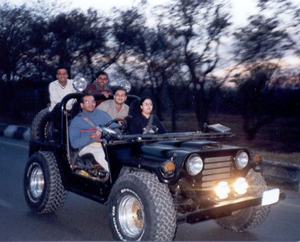

Sarmad was not a man who would covet others what he couldn’t do; there was no pettiness, only the genuine desire to see others achieve. “He was very big hearted that way,” says Zehra. “This was particularly admirable in his case because there was so much he wanted to do but was held back by his body.” His interests ranged in everything from sports, music and writing to cars and bikes. He never let it translate, however, into bitterness or frustration, always adjusting with ease and focusing on the next thing he wanted to achieve. Both being tremendously outdoorsy, a number of their activities revolved around athletic sports, be it bike riding, Sarmad’s well-known marathon runs, or off road excursions in their jeep.

With everyone he knew, Sarmad was a man who encouraged the pursuit of objectives. Passionate of living life and acutely aware of the smaller blessings, he had no patience with people who complained or were lazy and refused to help themselves. It disappointed him to see people who were able bodied but didn’t pursue opportunities to grow and take advantage of what they had.

“Anyone who realizes and is thankful for all the resources he has and plans to use them in the best possible manner is trying. Conversely everyone who keeps whining about the resources he does not have and blaming his fate or luck or the society or the man in the moon for that, is merely crying. Now for those who are in the habit of crying, I have no sympathy, or any words of advice. I am only concerned about those who are trying, or trying to try, or trying to try to try. For you, I have my whole life, all my experiences, all that I have learnt.”

|

Speaking at a motivational seminar |

Kamran Rizvi, founding director of the management consulting and training firm Navitus, met Sarmad when the latter was working at the HR department in an oil and gas company. An unerring sense for potential turned him onto Sarmad’s capacities. Sarmad expressed an interest in working in the training and consulting field and Rizvi encouraged him to take up the mantle of life coach and motivational speaker. This turned out to be a calling of sorts and was so successful a venture that many people began approaching Sarmad with ideas for creating a foundation or an NGO for physically challenged people. But to all of them his answer would be that simply because I’m trapped in a wheelchair does not mean that this is all that I’m about or this is all I want to channel my energies into and let define me.

For a man who consistently surpassed obstacles as a way of life, Zehra feels Sarmad’s biggest challenge was that of physical endurance, and he had a tremendous capacity for it. But it wasn’t just the marathons or the drive from Khyber to Karachi or the specially built machine to accompany other bike riders. “There were people who thought of his story as glamorous in some ways. Here was a man who, by refusing to let a disability define him, was now an individual whose achievements had brought him fame and accolades. I think this came from the fact that Sarmad would make everything look so effortless. But what a lot of them didn’t realize was the day to day challenges he had to deal with, the bodily complications he’d been living with every day for years,” says Zehra. For his part, Sarmad simply kept at it, invoking his faith and his belief in self to boost him forward, right up to the last days.

“Dear God, I know you don’t give anyone more than he can take, I know you wouldn’t let me break, you wouldn’t let my belief shake, but if it isn’t too much to ask, I really really need a break!”

For Zehra, the physical endurance aspect was Sarmad’s biggest challenge. And part of how he would deal with it was by refusing to take a break once he began on something, concerned that if he paused for a moment, his health might interfere and he wouldn’t be able to continue. “He was always full of plans and had big ideas. But out of every 50 of them, he’d only manage to achieve about 10, not, though, for lack of will or trying.” The consistent physical issues that kept arising might have sapped courage and engendered the temptation to simply give in. But Sarmad dealt with it differently, often telling Zehra, “My disability liberated me. I’ve been able to do and experiment with a lot of stuff, get away with a lot of crazy things.”

Zehra believes that her husband’s biggest achievement cannot be focused into one single accolade. “I’d say it was a series of achievements, which eventually culminated into his becoming a writer; a good writer and an intense writer. That’s his legacy, what he has left for those of us who remain behind him. He was eloquent and articulate and that’s how he touched as many lives as he has.”

|

As a couple, they never planned too far ahead. “Beyond what was necessary for planning in terms of work and career, we would only focus on the months ahead. Towards the very end, we left even that and began to live hour to hour.”

But when you talk to Zehra, and see her reminisce about her husband, there is no sadness, no inkling of a negative emotion. She is forward looking, and emanates a resilient positivity you wouldn’t expect from someone who has just lost a life partner. She credits her late husband for that. “He was never bitter, never sapped your energy or made you miserable because of what he was going through. He just made you stronger. He made me stronger as a person, for being around him. I don’t feel as if I can’t go on; I’m not confused or helpless about where to pick up life from. The fortitude and optimism is what he left me with.”

The author tweets at @Aiza_Azam

You may also like: