Written by: Haroon Shuaib

Posted on: August 18, 2022 |  | 中文

| 中文

Young Ashfaq Ahmed and Bano Qudsia

Bano Qudsia, born as Qudsia Chattah, is considered a leading writer of fiction, screenplays, and a proponent of traditional Sufism in Urdu literature. Born in Ferozpur, East Punjab in 1928, Bano migrated to Lahore with her family during Partition of the Indian-Subcontinent. Her father, Chaudhry Badr-ul-Zaman Chattah, a landlord and a very well-read man with a Bachelor’s degree in agriculture, died when she was quite young. Since her mother, Zakira Begum, was an educationist, she encouraged Bano to complete her higher education. After completing her Bachelor’s from Kinnaird College, Bano completed her Masters in Urdu from Government College, Lahore in 1951. Bano Qudsia’s only brother, Pervaiz Chattah, was a painter.

Bano started writing short stories when she was only in class 5, and continued to do so for college magazines and other journals throughout her academic life. While pursuing her Masters in Urdu at Government College, Lahore, she met her life partner, Ashfaq Ahmed, who was her senior at the College. Ashfaq Sahib later became a prominent Urdu writer in his own right. This short and simple campus romance between a strikingly good looking and popular Ashfaq Ahmed and a coy and simple Bano Qudsia, resulted in a union that brought two prominent Urdu writers together. The two perfectly complemented each other in their personal and scholarly journeys. Many claim that a lot in Ashfaq sahib’s thoughts can be attributed to direct or indirect influence of Bano, and vice versa. Bano on the other hand projected in her writings the image of a traditional and a devoted wife, which she was in her own personal life. After her marriage, Bano Qudsia, popularly known as ‘Bano Appa’ (a term of endearment for older sister) in literary circles, went on to establish her very own magazine “Dastango” (storyteller).

Bano Appa and Ashfaq sahib had three sons: Aneeque, Anees and Aseer. The couple was considered inseparable in their social lives and their house, “Dastan Serai” (The Storytellers’ Abode), in Model Town, Lahore, was considered an institution that drew writers, poets, artists, journalists, scholars and thinkers from across the country. The couple was always graciously hosting anyone who wanted to casually drop by, despite their own financial constraints. They were also regularly hosting literary evenings in their garden, and Dastan Serai soon became the center of the literary circles of Lahore. She emerged as a motherly figure who continued to mentor and patronize Lahore’s literati and budding writers, even after losing the anchor of her life after five decades of companionship in 2004, and despite her own failing health.

Bano Qudsia was a leading light in the literary and television circles due to her subjects, like the conflict between spiritualism and the demands of a modern society, her command over language and the craft of storytelling. This was an era when Urdu literature was soaring. Bano not only gained a loyal following for the plays she penned for radio and television, but her magnum opus, the novel ‘Raja Gidh’ (The Vulture King), immortalized her as a writer. Her other novels like Haasil Ghaat, Aik Din, Amar Bail and Footpath Ki Ghaas, consolidated her place as a leading writer of Pakistan.

Her drama for Pakistan Television, ‘Aadhi Baat’ (Incomplete Discussion), is considered an all-time classic. Her novel, Raja Gidh, received the most recognition. The metaphor of the novel is vulture, a bird of prey, which feeds on dead flesh and carcasses, and the moral of the story is that indulgence in the forbidden and worldly pursuits leads to physical and mental degeneration. Elaborating on her creative process, Bano once said, “Writing a book is like bearing a child, and you do not share that with anyone. God is your only confidant. It is also like falling in love. You keep it personal and private.”

In her writings, Bano propagated the traits associated with an ideal traditional society with customary moral values such as respect, harmony, a strong family system and ethics. She often lamented that these values were fast eroding under Western cultural influence. She was a firm believer in selfless love and contentment, and her ideas on feminism are problematic for the modern feminists. Her theme was that the deviation of woman from their natural roles as a mother and homemaker were actually the cause of their unhappiness and the overall degeneration of society. Bano felt that women’s inherent ‘strength of softness’ has been lost in their struggle to prove themselves equal to men. She prophesied that what women consider as their weaknesses are in fact their strengths. She lived her own life as a traditional woman, contrary to the modern ideals of feminism, preferring to stay under the shadow of the towering man in her life. She writes in her novel Hasil Ghat, “True love requires the strength to stay in a cage like a parrot, even after the realization that the door of the cage has been left open.” Despite the fact that many would argue against her seemingly regressive ideas, she remains an influential voice amongst the women writers of Urdu literature.

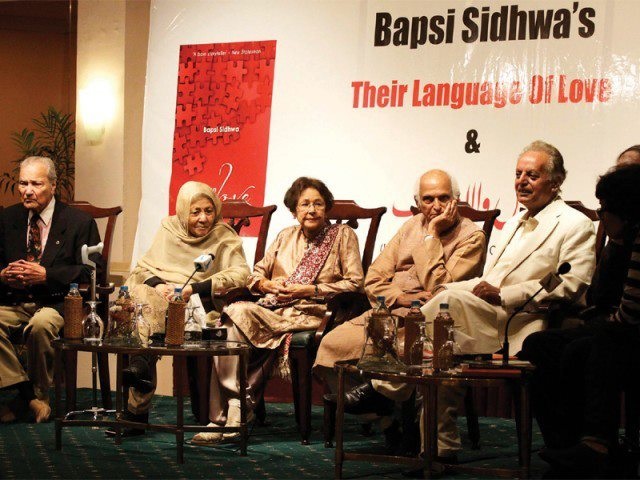

Javed Iqbal, Bano Qudsia, Bapsi Sidhwa, Intizar Hussain and Mustansar Hussain Tarar at the launch of Sidhwa’s book

Bano received the Graduate Award for Best Playwright in 1986, followed by the same award for three consecutive years from 1988 to 1990. In 1986, she was given the Taj Award for Best playwright. The Government of Pakistan recognized her contributions to literature and bestowed her with Sitara-e-Imtiaz in 2003 and the Hilal-e-Imtiaz in 2010. Pakistan Academy of Letters honoured her by awarding her with Kamal-e-Fun (Excellence in Craft) Award in 2010. She wrote more than 25 novels, two biographies and dozens of Television and radio plays. Bano breathed her last on 4 February 2017, and with her a powerful literary nucleus created by her and Ashfaq sahib in Lahore, came to an end.

You may also like: