Written by: Dr. Dushka H. Saiyid

Posted on: September 08, 2014 |  | 中文

| 中文

1857, fighting around Delhi

Raza Rumi’s book, Delhi by Heart, is an ode to a civilization and culture that flourished in Delhi from the time of the Sultanate and the arrival of the Sufi saints in the 13th century, till its final denouement in 1857, when the British ferociously crushed the revolt against their usurpation of power in the Indian sub-continent. It was a death knell not only for Delhi, but also for the Indo-Islamic culture that had flowered since the Sultanate period.

Rumi’s canvas is wide and buttressed by diligent research, as he explores the rich tapestry of Delhi’s past: Sufi saints, rulers, poets, architecture and the urban development of the city. Dehli was the nursery and home, of what he has described as the Ganga/Jamna culture, and he points out that the, “north Indian cuisine, language and manners evolved within the precincts of Delhi”. The richness and inclusiveness of the Indo-Islamic culture, and its’ fading away with the demise of the Mughal empire, is the theme of the book.

With an inclination towards Sufism, he mentions that five great Sufi orders migrated from Central Asia to India between the 12th and 15th centuries, coinciding with Muslim rule. They distanced themselves from the orthodox Ulama and were more inclusive, “and became the focus of religious syncretism”. Nizamuddin Auliya, was the pre-eminent Sufi saint of Delhi, and his dargah was open to people of all castes, creed and religion. He reflects on the relationship of Amir Khusrau with Nizamuddin, drawing parallels with that of Maulana Rumi with Shams Tabriz. It was Nizamuddin Auliya who instructed Khusrau to develop a language that could be understood by all. He quotes from the writings of Raj Kumar Hardev, who became a disciple of Nizamuddin Auliya: “When we were all present, Hazrat instructed us saying, ‘You all must get together and prepare a language that the Hindu residents of India, and the Muslims who have entered India, can both use easily to communicate in dealing with one another’.” Amir Khusrau is also attributed with being the founder of popular music tradition, as a synthesis between the indigenous music and the influences brought in by Muslims began to take place. Two of his disciples who founded Qawal Bachche, were given to him by Nizamuddin Auliya to give devotion a musical expression.

|

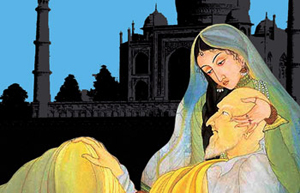

Emperor Shah Jehan with daughter Jahanara |

The centerpiece of the book is Shahjahanabad, whose name was changed by the British to Old Delhi. The author explores the labyrinthine streets of what was once the greatest city between Istanbul and Canton: Chandni Chowk, the beautiful market place with fountains and ponds, that foreign travelers visited with great fascination; Ghalib’s haveli, a fruitless search for Mir’s house, and the contribution of Jahanara, Shahjehan’s daughter, to beautifying the city of 150,000; the Red Fort, home to the Mughal royal family and its destruction and defiling by the British. However, the marginalization of Muslims is a recurring theme, whether it is in discussing the basti of Nizamuddin or the condition of Shahjahanabad, as they have become Muslim ghettos, although they continue to serve up delicious Mughlai food.

There is a chapter on some of the princesses who played a role in the unfolding of history, and were not simply silent spectators. He reflects on the dedication of Jahanara to her father, Shahjehan. Both she and her niece, Zebunisa, Aurangzeb’s daughter, were women of letters who asserted their independence within the confines of the patriarchal society of the day, and ran afoul of the puritanical and intolerant Aurangzeb. Razia Sultana makes a sympathetic appearance in his narrative, as does the attitude of the Turkish nobles, who regarded her love for an Assyrian slave as an unacceptable travesty of their norms.

The poets and writers emerge against a backdrop of tumultuous times. Mir’s poetry, more in the nature of a dirge, was a reaction to seeing the decimation of his city, first at the hands of Nadir Shah, and then Ahmed Shah Abdali in the 18th century. The city recovered, though the Mughal Empire was now in rapid decline. Ghalib's treatment, who was caught in the cusp of the death of an old order, being replaced by an imperious colonial power, is done with great empathy. While the poets and musicians had found patronage in the Mughal court, after 1857 they had to face the humiliation of petitioning the new alien masters for stipends.

The British replaced Persian with English as the official language, striking the first blow to Urdu. Partition and the adoption of Hindi, a more Sanskritized version of Urdu, struck the second blow. The crowning moment of Rumi’s trip to Delhi is his opportunity to meet Qurat-ul-Ain Hyder, whom he compares to Gabriel Garcia Marquez. The finest modern-day representative of the Ganga-Jumna culture, he recounts with delight his encounter with this giant of Urdu literature, her sense of history, and vivacious, witty and engaging presence. If the shifting sands of history could not diminish Ghalib’s genius, neither was Qurat ul Ain Hyder’s creativity dampened by the traumatic events of Partition, although they both suffered at a personal level.

|

Jamia Masjid, Delhi |

A journalist and a television discussant, with formal training in the field of development, Raza Rumi has now emerged as an important author, who combines knowledge and understanding of history and culture with great facility. He wrote the book wanting “to transcend boundaries and borders and reject the ills of jingoism”, but it does more than that, for it is all about self-discovery and getting to grips with our fractured identity in a post-colonial state.

You may also like: