Written by: Dr. Dushka H. Saiyid

Posted on: March 25, 2013 |  | 中文

| 中文

Zumbi dos Palmares

We decided to visit Salvador, the centre of Afro-Brazilian culture and history, despite its reputation of muggings of tourists.

The Portuguese first arrived in Brazil in 1500, landing near Salvador in a fleet carrying 1200 men, and were met by the indigenous Indians, living in a Rousseauist “state of nature.” Salvador became the first capital of the Portuguese empire, and it was only in 1763 that it was moved to Rio.

Since Brazil did not have commercially valuable ivory or spices, sugar was introduced as a cash crop in 1532. As the local Indians either escaped into the countryside, or were decimated by diseases introduced by the Europeans, African slaves were shipped in to work on the sugar plantations, as only they could survive the harsh plantation system. When the slaves were eventually emancipated in 1888, they numbered at least 3.6 million.

|

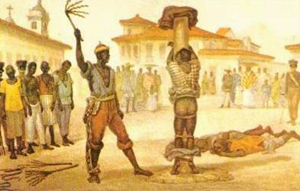

| Pelourinho or the whipping post |

Pelourinho is the historic center of Salvador, with a high concentration of historic churches, museums, and manifestations of African culture. Pelourinho means whipping post in Portuguese, and this was the old slave auction location in the days when slavery was common, which was outlawed in 1835. Women in traditional hooped skirts, and young boys performing capoeira, try to make money by posing for the photograph hungry tourists, while throbbing music pours into the street from the surrounding buildings.

|

| Orixas |

The Portuguese tried to convert the African slaves to Catholicism, if necessary, through coercion. Rather than assimilate and lose their cultural identity (what the great anti-colonial writer, Franz Fanon, condemned so forcefully), the slaves developed a culture of resistance. So a vast majority continued to practice Candomble, an amalgam of African religions, in secrecy. Their ceremonies, based on music and dance, were held in halls known as terrieros and lasted many hours. As the music picks up, the dancing becomes more frenetic. One of the dancers can become a medium for the orixas or the Candomble deities, and go into a trance, taking on the attributes of the spirit that has possessed them. It is some what similar to the trance that sufis and dervishes fall into at anurs, or annual celebration, at the shrines of sufi saints. Tourists can witness these ceremonies but by prior appointment and permission. Two museums carrying some of the artifacts representing Candomble practices and orixas are Museu Afro-Brasileiro and Museu da Cidade. The latter has a wide selection of orixa manequins dressed in their elaborate ritual costumes.

|

| Convento Sao Francisco |

The Portuguese seem to have assuaged their conscience by building a myriad of churches in the Pelourinho, from the proceeds of their profitable business in sugar and slavery. The most famous of these churches is Igreja e Convento Sao Francisco, an opulent display of gold and silver leaf work and an 80 kg silver chandelier. The slaves who worked as its artisans, although not allowed to practice their own religion, were forced to build churches by their masters. If they converted, the slaves would stand at the bottom of the church, while their masters sat in the pews.

The slaves developed capoeira, a form of martial arts for self-defense, but which has evolved into an acrobatic dance performed to music. It was a tool of survival, with which an unarmed escaped slave could accost the armed agents of the slave owners sent to capture them. It is now an art form performed on the streets and theaters of Pelourinho, and a source of tourist attraction.

Slaves would escape to remote areas and establish quilombos, or settlements for fugitive slaves. The biggest of these quilombos was the Quilombo dos Palmares, which consisted of many villages and lasted for over a century. Many warriors of Palmares, in trying to fend off repeated attacks by Portuguese colonists, became experts of capoeira.

A commanding statue of a black man adorns one of the squares in Pelourinho: full of dignity and defiance, representing the indomitable spirit of freedom, it is that of Zumbi dos Palmares. He led the quilombo of dos Palmares and refused to compromise with the Portuguese colonists. Palmares eventually fell, and Zumbi, who continued to elude the Portuguese, was betrayed by a quilombo and beheaded on November 20, 1695. His head was taken to Recife and displayed in a square, a lesson to other slaves aspiring for freedom. In modern day Brazil, November 20 is celebrated as a day of Afro-Brazilian consciousness.

It is reminiscent of the fate that befell the sons of the last Mughal Emperor of India. They were killed in cold blood when the war of independence of 1857 failed, and their bodies displayed for three days in Delhi; a chilling message for those hoping to break the stranglehold of East India Company over India.

Take away the infusion of African race and culture from Brazil, and it becomes just another Latin American country, without its unique, primeval art, music and culture. Modern day Brazil, unlike other countries with a history of slavery, celebrates its African heritage and heroes nationally, and retains the distinct influence of African culture on its society.

|

| Historic center of Salvador, Pelourinho |

Click to view picture gallery

You may also like: