Written by: Nimra Khan

Posted on: April 29, 2025 |  | 中文

| 中文

Untitled by Shahla Rafi

For the 17th anniversary of Gallery 6 in Islamabad, curator Arjumand Faisel brings an extensive presentation of artworks from diverse schools and styles that display a panorama of Pakistani art. With the absence of a thematic thread, the show is a sampling of works from landscapes to portraiture, abstract to calligraphy, executed with both traditional realism and more emotive modernist sensibilities.

A few of the artists present serene views of rural and urban life. Ajab Khan, Nazir Ahmed, and Shahla Rafi frame idyllic scenes of nature with sensitivity and precision. In contrast, Abid Hasan’s take is more a sensorial approach, with a process that is both meticulous and spontaneous. “My process is a unique blend of art and science, employing chemicals on silver and gold surfaces to produce spontaneous and instinctive works. Through a meticulous, five-step layering of chemicals, paints and metals, I create compositions that defy conventional landscapes and invite viewers to explore the invisible and undiscovered aspects of our world,” he explains on his website. Thus, works like “Blueprint of Survival” is a landscape that is felt rather than seen, and reflects concepts that go beyond the visual.

Similarly, Anila Zulfiqar’s chaotic amalgam of shapes captures the soul and essence of an urban sprawl as compared to the direct depiction of urban life by Arshad Maqbool. In “Urban Soulscape” I and II, Zulfiqar conveys the sensory experience of the urban space – the cacophony, visual clutter, congestion, movement – through stylized overlapping form creating a mosaic of amorphous shapes loosely resembling a cityscape.

Akram Spaul, in an Untitled piece, depicts a sparse still life in photorealism. With warm natural life beautifully translated to shapes falling upon a lone chair, and a table with an upturned book, there is a sense of stillness in the scene, like an in-between moment captured. The sense of absence is palpable. On the other hand, Aftab Ahmad’s take is more modernist, with a gestural application and flattened perspective creating a sense of tension between foreground and background.

Maqsood Ali and Mobina Zuberi present works with color fields of geometric abstract shapes which are reminiscent of Abstract Expressionism where artists like Mark Rothko diluted art down to emotive and visceral color studies. Here there a lot more texture, with subtle variations in shade. While Ali’s work seems aglow from within, pulling you into itself, Zuberi’s appears almost opaque.

Many of the works focus on portraiture and the human figure. Artists like Ather Jamal and Ali Abbas are featured with images of rural Sindhi women in traditional garb, painted in their signature watercolor style. Aun Raza uses Realism and a straightforward composition to make a political statement with his work “Beti Parhao, Beti Bachao”. Other works choose modernist stylization, such as Mansoor Rahi, whose reclining figures are engaged in activities while fusing into the geometric backgrounds. Mansur Aye chooses a more minimal approach with portraits etched in simplistic, gestural linework, giving the vague sense of a memory.

Arjumand Faisel’s “Sheltered in Love” uses pastels to create texture that adds depth to the diffused portraits of a family. The delicate line and hues create an emotive experience. In Hajra Mansoor’s work this texture becomes even more intense with a slightly more dynamic color palette, granting more complexity to the paintings. The portraits combine Mughal portraiture with modern styles, resulting in simplified yet overly beautified visuals, with a childlike sensibility.

S. Rind uses his signature style with charcoal to create highly stylized figurative works. His sharp lines couples with dark shaded area create the illusion of calligraphic forms. Rind talks about societal inequalities, depicting the powerless women from his childhood, using the symbol of the crow to depict fear and domination. Farrukh Shahab uses similar visual devices in his “bird series”, but with a wildly different visual style. His busy canvases show large, colorful birds in mixed media, foliage, the female form, and indistinct text. Wahab Jaffer also paints colorful portraits with stylized birds as head dresses. His style is more visceral, executed in pen and markers and reminiscent of the portraits by Henri Matisse.

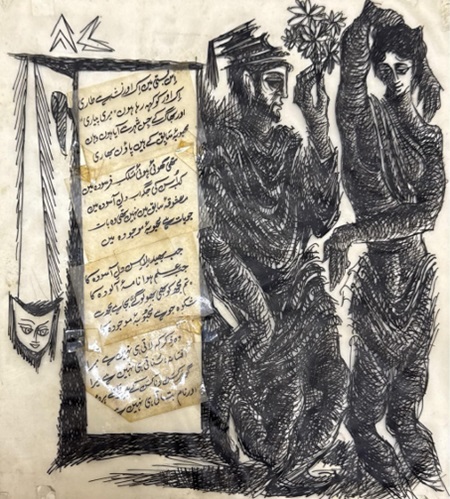

A few artists use their portraits along with other motifs to weave a more complex narrative and launch commentary on the world around them. Akram Dost Baloch takes influence from traditional Balochi motifs, including embroidery, wood carving and weaving. Here these patterns are layered around his very distinct faces, male and female, placed close together, seemingly talking about deep connection and intimacy in this specific cultural context. Two works by Sadequain are also included, executed in the artist’s distinct signature style for a book, talking about love, deceit and betrayal.

Mutaib Shah uses a surrealistic visual language to pose ecological and spiritual questions. A lone man squats atop a severed tree stump engrossed in his mobile screen against a barren landscape and a sky ripped apart. The faces of a sufi malang and a maulvi sail turbulent seas together, yet with their eyes shut. The sharp facial features create a unique visual language, and the artist uses color to create a dramatic effect.

Nazar ul Islam’s portrait is a unique blend of realistic depiction and stylization. Stark accessories serve to bring our attention towards the dark skin, with highlights to further accentuate the facial features and bring a sheen to the smooth skin. Islam seeks to challenge racial bias and uses contrast to “celebrate black as graceful,” according to his statement.

With many notable names from the Pakistani art scene, the show allows the viewer to witness an extensive range of works from old masters to contemporary gems. The variety in themes, styles and genres demand a curatorial narrative to reign them in, however, the connections emerge seamlessly as the works are experienced together, providing contextual weight to the viewing – a testament to the strength of the works.

Drawing for a page of the book 'Rubbaiyyat Sadequain Naqash'

Sehra Gard by Ali Abbas

Untitled by Hajra Mansoor

You may also like: