Written by: Haroon Shuaib

Posted on: November 15, 2023 |  | 中文

| 中文

Altaf Mir (center) playing his harmonium

It was till 1990 that a 20-year-old Altaf Mir was living in Janglat Mandi neighborhood of Anantnag city of Indian Illegally Occupied Jammu and Kashmir. He was an embroidery artist specializing in traditional Kashmiri chain-stitch, and doubled his earning as a bus conductor. Witnessing the atrocities of Indian military on his people, Altaf, who is also fond of music and poetry, got so disillusioned that he left his home quietly migrating across the border to Azad Jammu and Kashmir. Life in the illegally occupied Kashmir has not been easy, especially for young men, who are regularly subjected to humiliation, torture and even threat to their life at the hands of Indian occupying forces. For decades, Kashmiri people have been struggling for their inalienable right of self-determination. The longing for his home and family never fades for Altaf. It was perhaps his sensitive nature that didn’t let him come to terms with the prevalent injustice. Once settled in Muzaffarabad, capital city of Azad Jammu and Kashmir, he decided to channel his pain in more productive pursuits and introduce art, craft, poetry and music of his land to the world. Altaf has joined a local NGO working for the rehabilitation of displaced families in Kashmir, and is training boys in the art of traditional Kashmiri embroidery, handicrafts and music.

The word ‘Kashmir’ is derived from Sanskrit words, ‘Ka’, meaning water and ‘Samira’, meaning wind, referring to a geological incidence of a large lake drying out due to wind. Huientsang, a Buddhist scholar and Chinese traveler, called Kashmir kia-shi-milo. In the Kashmiri language itself, Kashmir is known as Kasheer. In some historic accounts, the region has also been referred to as ‘Kashmira’ or ‘Qasamira’. It is from ‘Qasamira’ that Altaf Mir derived the name for his musical band, ‘Qasamir’. Kashmir is a land of rich linguistic, cultural and artistic heritage, where poetry and musical traditions are deep-rooted. It is through Qasamir that Altaf wishes to keep these traditions alive, and hopes for a day when the region known as ‘Kashmir – Jannat Nazir’ (Kashmir, Paradise on Earth), unfairly torn into two, will be reunited.

From 1990 to 1995, Altaf remained completely out of touch with his family, except for an occasional phone call that would cost him an arm and a leg, not to mention the local authorities in Anantnag coming knocking on his mother’s door each time he would call. He did return to his home for a few months in 1995. To keep his mind away from the oppressive conditions around him, he busied himself by regularly performing music at weddings and in sufiana mehfils (sufi congregations), mostly spending time at the mystical music gatherings in Chrar, a town in Budgram district, and at the shrine of Kashmir's most respected saint, Sheikh-ul-Aalam. When the Indian army launched its infamous ‘Operation Catch-and-Kill’, his house was raided thrice. Fortunately, he was not at home each time, and soon decided to again leave for Muzaffarabad, never to return again.

Life as a refugee was hard, but slowly and gradually he got used to his new surroundings. Married to a local lady Fozia with four sons and a daughter, music remains Altaf’s first love and he is more than happy whenever he gets invited to perform anywhere in the valley, or even as far as Islamabad. It was a performance at a friend’s wedding which was also attended by someone from Muzaffarabad Radio Station that opened new doors for Altaf. He was invited for an audition the next day, and after listening for just a few minutes the radio producer gave him five assignments. Altaf started doing five shows a week for radio, singing Kashmiri songs. Invitations from official parties started pouring in on a daily basis. When the first television channel was launched in Muzaffarabad in 2004, he was asked to perform at its opening ceremony. With a group of musicians, some local and others migrants like him from Indian Occupied Kashmir, Altaf formed ‘Qasamir’ in 2018.

With Altaf as the lead vocalist, Qasamir shot to overnight fame at the national level, when they featured in the fifth and final song of ‘Coke Studio Explorer’ the same year. Other members of the band include Ghulam Mohammad Daar, who has been associated with Radio Pakistan Muzaffarabad as a Sarangi player for over 40 years. Manzoor Ahmed Khan was a rickshaw driver and Saifuddin Shah worked as a chef, and they both played ‘noet’ (pitcher) and traditional Kashmiri percussion ‘tumbaknaer’. Created by musicians Ali Hamza and Zohaib Kazi, the series was a spin-off of popular music platform Coke Studio, as a prequel to eleventh season. Instead of studio recordings as done in its original format, explorer series of Coke Studio featured live music of regional, but largely unknown artists, from across Pakistan. Qasamir contributed a track titled ‘Ha Gulo’ (oh flower), a song about love and longing, written by the noted poet Peerzada Ghulam Ahmad Mahjoor (1887 − 1952), who is also known as Shair-e-Kashmir (Poet of Kashmir) and father of the Kashmiri language.

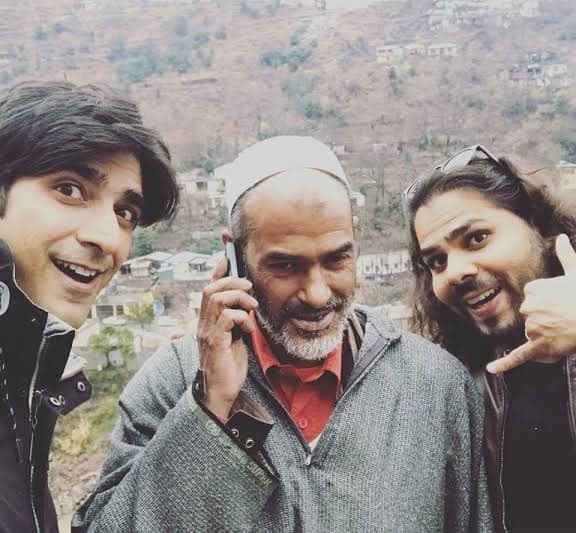

(L to R) Ali Hamza, Producer,Coke Studio, Altaf Mir and Zohaib Kazi, Associate Producer, Coke Studio

Born in Pulwama, Mahjoor started writing poetry under the influence of great Urdu poet, Shibli Naumani. Writing in Persian, Urdu and Kashmiri with equal ease, Mahjoor used the simple diction of traditional folk storytellers in his writings, focusing on the natural beauty of Kashmir and urging his fellow countrymen to stand up against various forms of injustice. Rabindranath Tagore of Bengal, Mahjoor’s contemporary and the first non-European and the first lyricist to win the Nobel Prize in Literature, called Mahjoor 'Wordsworth of Kashmir’. ‘Ha Gulo’ is a beautiful piece of Majhoor’s poetry that resonated with Altaf’s own life journey.

Ha gulo tohi ma sa wuchwan yaar meon– Oh flower, have you seen my beloved?

Bulbulu tuhi tcahari toan gulzar miyon – O nightingale, help me find my love!

Ash rozum yaar watym az pagah – I remained hopeful my love will come today or tomorrow

Yi karaan soran aw lokchar miyun – In this hope my youth faded away

Ath tareeqas peth chaliyuv bapar miyun – Like this my story kept on going

A drop out after Class 6, Altaf can read Kashmiri fluently and has memorized more than 2,000 ghazals and other poetic works of classical Kashmiri poets such as Faqeer Samad Mir Soeb, Habba Khatoon, Rasul Mir, Rahman Dar, Nyam Saeb, Mehmood Ghami, Ahad Zargar, Momin Sahib and Wahab Khar. He has many books of Kashmiri poetry and prose in his house. For ‘H Gulo”, he used traditional musical instruments of Kashmir. Tumbaknaer is an earthen-shaped instrument used for singing at all Kashmiri functions, particularly weddings. The instrument is thought to have originated in Iran. Altaf had brought a tumbaknaer with him from Anantnag, but over time it cracked, and now he is only left with a few wooden ones that unlike the Kashmiri ones, trace their origin back to Central Asia. The potters here neither have the skill nor the right clay to make a new one for Altaf.

Noet is a kind of an ancient drum variety, and noet of Kashmir is similar to ghatam of South India or the matki of Rajasthan. Now often made of brass or copper, the traditional Kashmiri noet is an earthenware pot and it is believed that water should never be stored in a noet meant to produce music, otherwise the music gets distorted. It is ironic reference to the legend of the land of its origin, drawing its own name from a lake drying out due to wind.

Altaf’s mother, Begum Jaan, saw the video of ‘Ha Gulo’ on a phone, and was both ecstatic as well as torn with tears rolling down her cheeks. She was happy to see Altaf in the video singing and dancing along with his group members wearing ‘Ferans’, traditional robe-like dress, and skull caps adorned with traditional Kashmiri embroidery. Although she had visited him twice via the Wagah Border, she wanted to see her son one more time before she left the world, but that was not to be. Altaf could not attend her funeral but is sure that his music brought her comfort during her last few days.

You may also like: