Written by: Mahnoor Fatima

Posted on: November 17, 2020 |  | 中文

| 中文

Western Wall of Cave 45, from the Tang Dynasty

Beneath sandy dunes on the outskirts of Dunhuang, lies a treasure trove which is so unique that its parallel could only be found in fiction: the vibrant and historically important Mogao Caves. Located in the Gansu province of China, this is a UNSECO world heritage site and the largest, most renowned collection of Buddhist art in the world. But besides being a fantastic reservoir of Buddhist history and aesthetics, the religious works of art found in these caves were some of the first signs of artistic and cultural exchange between traders on the Silk Road.

Moving from Central Asia to China, the Silk Road was divided into two paths by the vast and unforgiving Taklamakan and Gobi deserts. Both routes were marked by oasis towns, where traders often stopped to rest or get provisions. Dunhuang (which means ‘Blazing Beacon’), one of the oasis towns, was also a military post where the two routes converged and the West made contact with China. Traders in Dunhuang would often leave behind objects from their travels or hometowns in these places. This did not just include material things like textiles, food or luxury goods, but also new ideas, religion and culture.

For instance, Buddhism, which was started in India, owes much of its spread through Asia to the Silk Road. Religious sites, like the Mogao Caves, were particularly important because they allowed traders to congregate en mass and either pray for a successful journey across the desert or to give thanks for a prosperous expedition.

According to historians and archaeologists, work on the Mogao Caves started from the 4th Century CE and continued to the 14th Century, when the Silk Road was abandoned. Based on the artifacts, anyone who visited the Mogao Caves either practiced or was empathetic to Buddhism. The first record of a cave painting is by a Buddhist monk named Le Zun (or Yuezun) in 366 CE, after he was said to have visions of thousands of Buddhas in golden light. This is why Mogao is also called the ‘Cave of a Thousand Buddhas’, as thousands of monks followed Le Zun in painting these walls with Buddhist imagery.

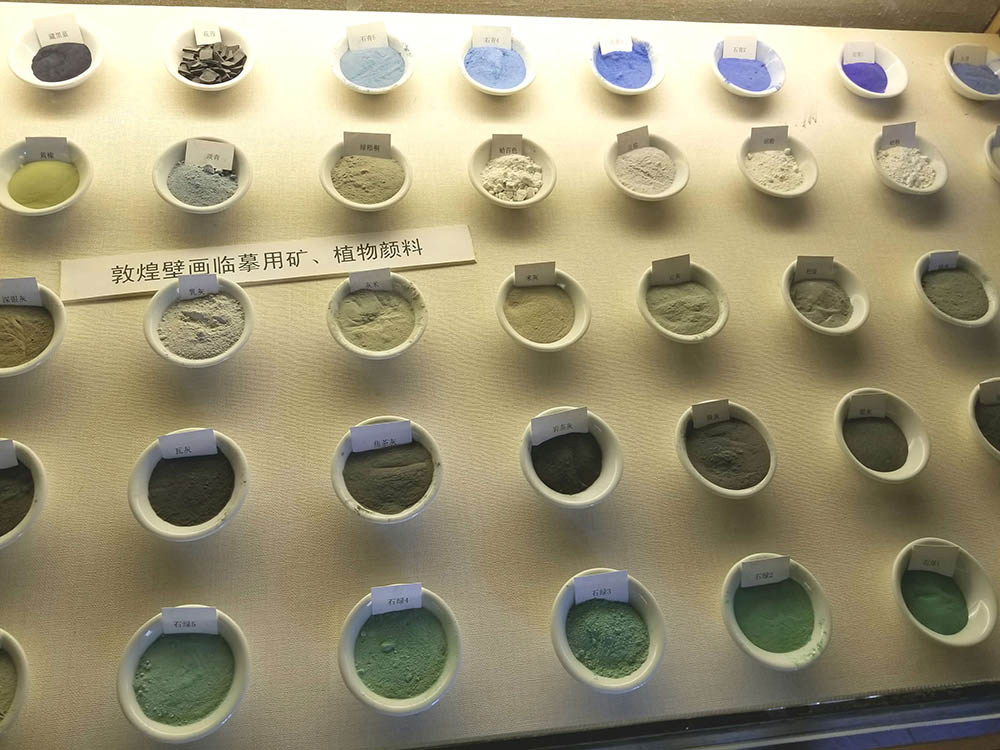

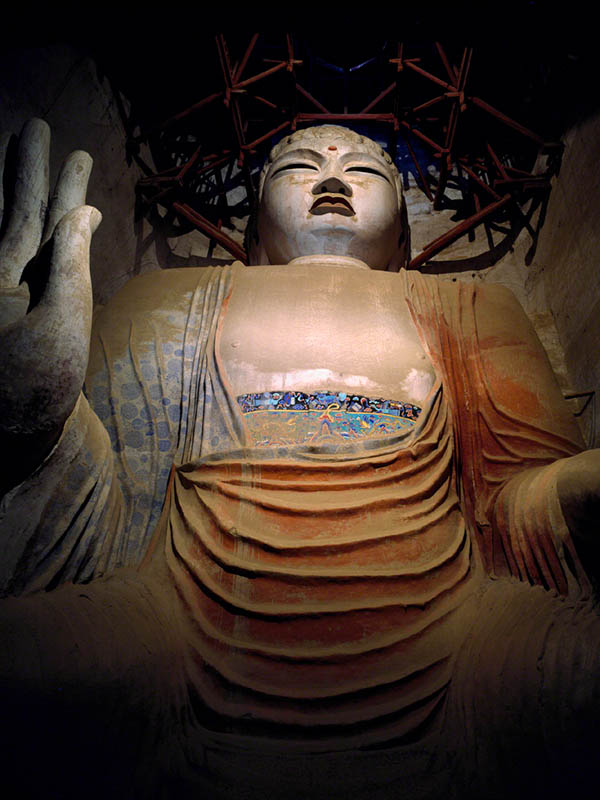

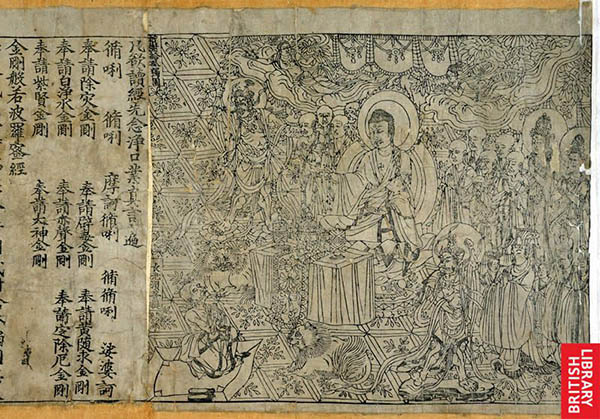

The caves are all man-made, and the artists had to adjust to the constantly shifting nature of the rocks. The paint was made of ground up minerals which have allowed the thinly-painted frescos to keep their hues over the centuries. However, the painters at Mogao also infused the paintings with colors and concepts from all parts of the Silk Road. The largest statue is over 34.5 meters tall, while the smallest is only 2cm high. One very important artifact is the Diamond Sutra (868 CE), a sacred Mahayana Buddhist text and one of the earliest printed books, which showcases China’s sophisticated printing mechanisms.

While Buddhist religious art is the main focus of these paintings, it is the intermingling of images and aesthetics that makes the Mogao caves so unique. Each painting served a purpose, whether to aid meditation, provide a visual representation of spiritual transcendence, or to simply teach people about Buddhism. However, archaeologists noticed images on these walls that have been more closely associated with the travelers on the Silk Road than they have to Buddhism. These include Central Asian merchants with red hair and long noses, Indian monks in robes and Chinese peasants working the land. Much of this work was done during the Tang Dynasty (618-907 CE), when Chinese and Central Asian motifs came together to make the Dunhuang Style.

The Caves started to lose relevance when the Silk Road was abandoned for sea travel, and the rise of Islam in Central Asia overshadowed the spread of Buddhism. The invaluable old Buddhist texts and paintings were stored and hidden behind a wall painting in one of the caves. These paintings were eventually discovered in 1900 by a Buddhist abbot named Wang Yuanlu, but it would take seven more years till Silk Road historian Aurel Stein and his contemporary Paul Pelliot, would begin to study and collect them. In a letter, Pelliot remarked to going through over a thousand scrolls in a day. Many other explorers came to the caves in the early 20th Century to take manuscripts, and as a result, the cave artifacts are scattered all over the globe.

Overall, there are currently 735 caves, 492 of which still have paintings and sculptures inside them. The cave complex is divided into two sections, with the southern section as the more decorative and colorful. While the murals outside have been eroded, the murals inside are still in good condition. However, tickets to see the caves are limited and quite expensive, so as to protect the delicate paintings from the humidity and carbon dioxide that tourists bring into the caves.

Fan Jinshi, the director of the Dunhuang Academy that is in charge of the research, conservation and tourism of the site, explained that the Caves are something of a time capsule of the Silk Road. One can see the intermingling of Chinese and foreign elements on each grotto painting. Indeed, the Mogao Caves are an endlessly fascinating site that shows how ideas and imagery traveled on the Silk Road, shaping people’s beliefs for centuries to come. The number of intellectually rich documents unearthed from the site are vital to understanding how the past has determined global connections and exchanges of ideas.

You may also like: