Written by: Dr. Dushka H. Saiyid

Posted on: December 23, 2022 |  | 中文

| 中文

Quaid-e-Azam Muhammad Ali Jinnah Addressing the First Constituent Assembly on 11th August 1947

The Cabinet Mission Plan of 1946 was the last attempt by the British to keep India united. The Quaid felt betrayed by the Cabinet Mission in not asking him to form the government as they had promised, if the Congress turned down their proposals. It was only then that the Quaid, for the first time, abandoned his constitutional struggle and declared August 16 as the Direct Action Day. Tragically, it resulted in an orgy of violence in Calcutta.

After the failure of the Cabinet Mission, a frustrated Viceroy Wavell decided to form an Interim Government with four representatives of the Congress, and an equal number from the Muslim League. The Quaid nominated Liaquat Ali Khan to lead the Muslim League team, which included Abdur Rab Nishtar, Ghazanfar Ali Khan, I.I. Chundrigar and J.N. Mandal, an “untouchable” from Bengal. The new cabinet was sworn in on the 26th of October 1946. Tension persisted in the cabinet, and there was little sense of harmony or unity.

The communal situation continued to deteriorate in Bengal and Bihar. The Congress pressured Wavell to call the Constituent Assembly to meet on December 9th, but the Quaid announced on November 22nd that the Muslim League would not participate in it. Nehru had made clear that decisions in the Constituent Assembly would be made on the basis of a majority vote, which meant Congress decisions would prevail. Since the Congress position was that the Constituent Assembly would decide on whether to accept the grouping proposal of the Cabinet Mission Plan, not surprisingly, the Quaid decided that the Muslim League would not participate in it.

With this setback, the Secretary of State for India invited Wavell to come to London with two representatives of the Congress and two of the Muslim League. After a few glitches, the Quaid, Liaquat, Nehru and Baldev Singh flew to London with Wavell. However, since the deadlock persisted, the British Cabinet met on the 6th of December and issued the following statement:

“Should a Constitution come to be framed by a Constituent Assembly in which a large section of the Indian population had not been represented, His Majesty’s Government could not of course contemplate – as the Congress have stated that they would not contemplate – forcing such a Constitution upon any unwilling parts of the country.”

(L to R) Mr Jinnah, Liaquat Ali Khan, Sardar Baldev Singh and Lord Pethick-Lawrence arrive in London in December 1946 (from Getty Images)

The dye was cast for the creation of a homeland for Muslims. The opposition led by Churchill, was openly supportive of the Muslim League. He declared in Parliament in a long speech, where he reminded his listeners of his prediction as early as 1931 of a civil war between Muslims and Hindus in India, if the British didn’t keep a watch. He went on to say:

…The Muslims numbering 90 million …comprise the majority of the fighting elements in India… the word “minority” has no relevance or sense when applied to the masses of human beings numbered in many scores of millions…

Realizing that a fresh hand was needed to break the deadlock, Atlee summoned Lord Louis Mountbatten on 18 December, and replaced him as the new Viceroy of India. His liberal ideas and royal blood made him acceptable to both Labour and the Conservatives. On 20th February, 1947, Attlee declared in the House of Commons that, “His Majesty’s Government desire to hand over their responsibility to authorities established by a constitution approved by all parties in India…but unfortunately there is at present no clear prospect that such a constitution … will emerge… His Majesty’s Government wish to make it clear that it is their definite intentions to take the necessary steps to effect the transference of power into responsible Indian hands by a date not later than June 1948…” The Indian political parties had been given a deadline.

The Punjab was engulfed with communal riots that began in the last week of February and continued well into April, spreading to the North West Frontier (now Khyber Pakhtunkhwa). All major cities of the province were gripped by violence, and it was spreading to the rural areas too. Khizar, the Premier of Punjab, who had been at loggerheads with the Muslim League, was forced to resign on the 2nd of March. The Congress Working Committee met on March 8th and resolved that if the Muslim League did not join the Constituent Assembly, “ the division of Bengal and Punjab becomes inevitable”. The Congress had been forced to concede Pakistan, albeit only the Muslim districts of Punjab and Bengal.

Mountbatten arrived in New Delhi on 22nd March 1947. His orders were to try to hand over power to a unitary government for British India and the Indian States, if possible within the Commonwealth. However, if this was not possible by October 1, then he was to advise the British government on the steps required for handing over power on the due date.

(L to R) Sir Samuel E. Runganadhan and Sir Malik Khizar Hayat Khan attending a party during the Peace Conference in summer 1946

Suhrawardy, the Premier of Bengal, wanted to retain a united Bengal, and the Quaid was willing, but Patel and Nehru feared that a Bengal led by a Muslim Prime Minister would form close links with Pakistan. When Mountbatten met Jinnah on April 26, and asked him what he thought of Suhrawardy’s demand to keep Bengal united and out of both India and Pakistan, the Quaid’s response was, “I should be delighted. What is the use of Bengal without Calcutta; they had much better remain united and independent; I am sure that they would be on friendly terms with us”.

The Mountbattens had left for Simla in May, taking Nehru and his daughter along with them. When Mountbatten received the news from London that the Partition Plan had been approved, the Viceroy, unethically shared the Partition Plan with his houseguest, Pandit Nehru. Next morning, on the 11th of May, Nehru gave his written response to the Plan, expressing his vehement opposition to it, and declaring that it would effect Indo-British relations very adversely. His main criticism was that if implemented, this Plan would lead to the Balkanisation of India, since it allowed the States to become independent first, and then chose which country to join.

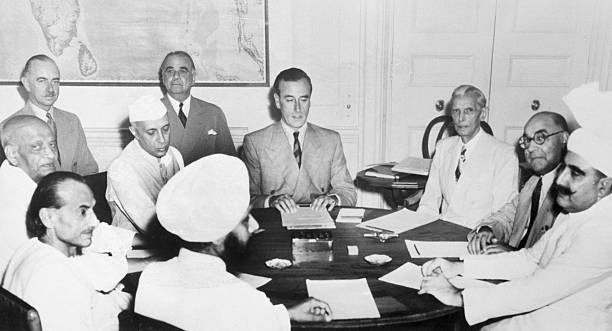

(L to R) Sardar Baldev Singh, Acharya J.B. Kripalani, Vallabhai Patel, Nehru, Lord Mountbatten, Muhammad Ali Jinnah, Liaquat Ali Khan and Sardar Abdur Rab Nishtar discuss the Partition of India in 1947.

(Seated at the back L to R) Sir Eric Mieville and Lord Ismay.

Jinnah was even more upset with the partition plan, and most unhappy at the partition of both Punjab and Bengal, and he was adamant that Calcutta should not be separated from Bengal. Jinnah argued that before any decision about the partition of the provinces was taken, a referendum should be held to determine the wishes of the people. However, Mountbatten vetoed the idea saying it would only delay the process, and the British Cabinet agreed with him. On June 3rd, Mountbatten announced the partition plan over the All-India Radio, followed by speeches by Nehru, the Quaid and Baldev Singh. It was specified how the referenda of different legislative assemblies would be held to decide by a simple majority on partition.

On June 20th the Bengal Legislative Assembly voted for the partition of their province, as did the Punjab assembly, while the Sindh legislature voted to join Pakistan. When Mounbatten called a meeting of the partition council, attended by Nehru, Patel, Baldev, Jinnah and Liaquat, it was decided to have two judges each sponsored by the Congress and the Muslim League, and the Quaid suggested the name of the eminent barrister, Sir Cyril Radcliff, to chair the boundary commission. Radcliff arrived in Delhi on July 8th and had exactly five weeks to draw the boundary lines between the two countries.

Mountbatten was keen to become the Governor-General of both the dominions, but the Quaid would have none of it, being aware of the close and intimate relations between Nehru and the Mountbattens, and his partiality towards the Congress.

Pakistan’s constituent assembly met for the first time on August 11, and unanimously elected the Quaid to preside over its meetings, who made a long and an important speech setting out his priorities. Amongst the many things he mentioned was, “that the first duty of a Government is to maintain law and order, so that the life, property and religious beliefs of its subjects are fully protected by the State”. Then he became introspective and philosophic about partition: “On both sides there are people who may not agree with it, who may not like it, but in my judgment there was no other solution and I am sure future history will record its verdict in favor of it.” And it was in this same speech that he uttered the famous and potent words: “You may belong to any religion or caste or creed-that has nothing to do with the business of the State. …We are starting with this fundamental principle that we are all citizens and equal citizens of one State.” All these guidelines were forgotten soon after the Quaid, the helmsman and the progenitor of Pakistan, passed away a year later, having singlehandedly conjured up Pakistan against all odds.

The Mounbattens arrived in Karachi on August 13, and the next day the Quaid accompanied by Fatima Jinnah, and Lord and Lady Mountbatten drove to the Sindh Assembly, which now housed Pakistan’s Parliament. Mountbatten read out King George’s message welcoming Pakistan into the Commonwealth, and the Quaid graciously responded. They flew back to Delhi that same afternoon for India’s celebrations of its independence on August 15. Same day the controversial Radcliffe Award was announced, and an orgy of communal killings began on both sides of the border as millions moved to their new homes. Pakistan’s birth had been baptized with fire.

You may also like: