Written by: Haroon Shuaib

Posted on: January 06, 2022 |  | 中文

| 中文

Raja Rasalu is one of the most popular folk heroes of The Punjab

Raja Rasalu, like many other world epics, is not just a literary masterpiece, but also a very intriguing insight into the worldview of the people of the region from where it originates. Like ‘Alif Laila’ (Thousand and One Nights) of the Middle East, Epic of Sundiata of West Africa, Xī Yóu Jì (Journey to the West), a Chinese novel published in the 16th century and the Slavic epic ‘Tale of Igor's Campaign’, Raja Rasalu’s tale is woven deeply in the social fabric of Punjab. Part oral, part documented, part fact and part fiction, as is the case with most world folklores, no one knows for sure when and where the story of Raja Rasalu came into being for the first time and how many narrators contributed to it, as it passed from generation to generation. What is known for sure is that Raja Rasalu was born in the region that today forms Sialkot.

In a published form, legends of Raja Rasalu were first published in the most comprehensive form by Flora Annie Steel, an English writer who lived in India for 22 years in her book ‘Tales of the Panjab’, published in 1894. She based her narration on the songs of wandering minstrels. Her book was beautifully illustrated by John Lockwood Kipling, an English art teacher, illustrator and museum curator who spent most of his career in India. The same story was earlier gathered by Joseph Jacobs in his ‘Indian Fairy Tales’, published in 1892 but with many omissions.

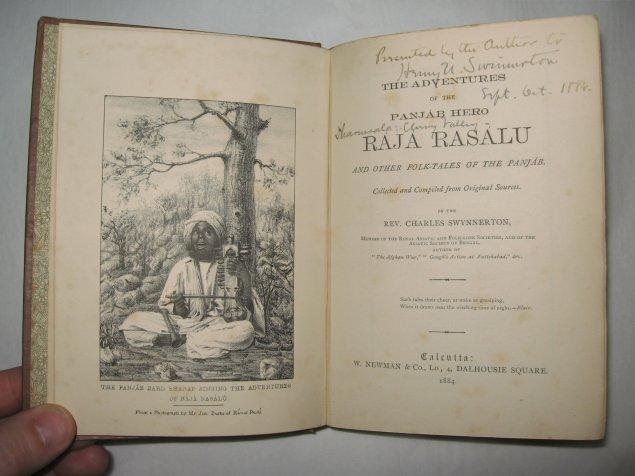

Rev. Charles Swynnerton's The Adventures of The Punjab Hero Raja Rasalu and Other Folktales of The Punjab - Published in 1882.

This account of Raja Rasalu begins with the introduction of the two sons of Raja Salbahan, Puran and Rasalu. Salbahan had two queens; the elder was Queen Achhra, who had a son called Puran, but the younger queen, Loona ‘wept and prayed at many a shrine, but never had a child to gladden her eyes.’ Envy and rage took possession of Loona’s heart and she slowly poisoned Raja Salbahan's mind against young Puran. As the Prince grew into manhood, his father became madly jealous of him. In a fit of anger, he ordered that hands and feet of the prince be cut off and he be thrown into a well. As fate would have it, Puran survived in that well without arms or legs, fed by birds and cared for by animals for twelve years, until a saint pulled him out. Through his supernatural powers, the saint restored Puran’s limbs and granted him supernatural powers. They say that for the twelve years that Puran had been banished, the Sialkot trees bore no fruit, birds sang no song and cows gave no milk.

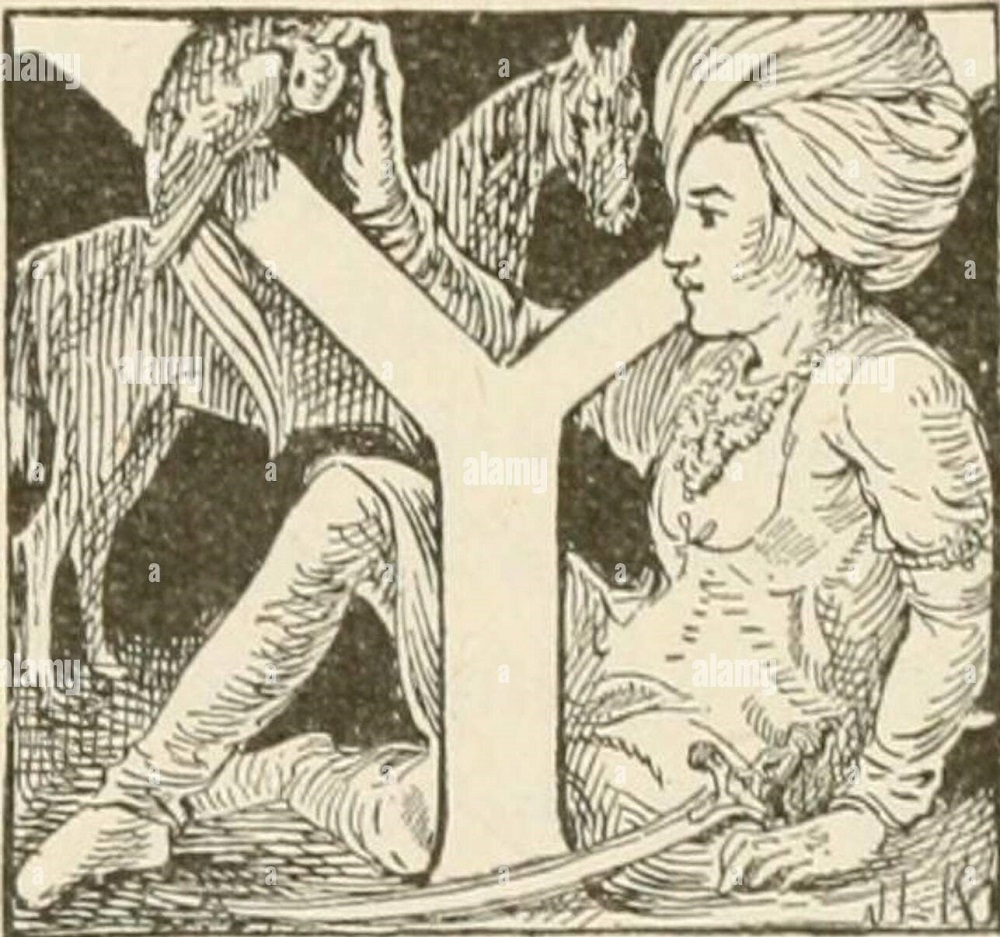

A young Raja Rasalu with his faithful stallion 'Bhanur’ or ‘Fauladi Iraqi’, and the wise parrot 'Shadi'.

Loona too remained childless much to her grief. It was only on Puran’s return, now a saint himself, that with his blessings, she finally was blessed with prince Rasalu. The saint whose identity remained a secret, put the condition that neither parent was to set eyes upon Rasalu for twelve years. If they did not abide by this condition, all three were to perish instantly. For twelve years, Rasalu, the newborn, was to remain confined in an underground palace along with a faithful stallion 'Bhanur’ or ‘Fauladi Iraqi’, and the wise parrot 'Shadi'. Six months short of the prescribed period, he broke out and demanded that he be taken to his father. The wish could not, of course, be granted. Frustrated, disillusioned and finally banished from his land, Rasalu embarked on a journey which formed the adventures of Raja Rasalu. Aitzaz Ahsan in his book ‘The Indus Saga and the Making of Pakistan’ recounts, ‘Astride Fauladi, with Shadi perched on his shoulder, his arrows weighing one hundred pounds each, Rasalu takes to the wilderness, passing from one land to another, fighting demons, marrying damsels, solving riddles and putting out strife and fires to become the foremost folk hero of medieval Punjab.’

One of his journeys took Rasalu to Nila city and as he entered the town, he saw an old woman crying while making bread. On Rasalu’s inquiry she narrated, ‘I had seven fair sons, and now I have but one left, for six of them have been killed by a dreadful giant who comes every day to this city to receive tribute from us; every day he takes a fair young man, a buffalo and a basket of cakes! Six of my sons have gone, and now today it has once more fallen to my lot to provide the tribute; and my boy, my darling, my youngest, must meet the fate of his brothers. Therefore, I weep!’ Rasalu was moved as he recalled his longing for his mother. He told the old woman not to worry as he will ensure her son’s safety. ‘Still the old woman shook her head doubtfully, saying, "Fair words, fair words! But who will really risk his life for another?" Then Rasalu smiled at her and dismounting from his gallant steed, Bhanur Iraqi, he sat down carelessly to rest, as if indeed he were a son of the house, and said, "Fear not mother, I give you my word of honor that I will risk my life to save your son."

When the time for the offering came, Rasalu mounted his horse and taking the basket of cakes and the buffalo, he set off to find the giant. As he came near the giants' house, he met one of them carrying a huge skinful of water. When the giant saw Raja Rasalu riding on his horse and leading the buffalo he said to himself, ‘Oho, we have a horse extra to-day! I think I will eat it myself, before my brothers see it!’ As the giant reached out his hand, Rasalu drew his sharp sword and smote the giant's hand off. As the giant fled, he met his sister, a giantess who called out to him, ‘Brother, where do you run so fast?’ The giant responded, ‘Raja Rasalu has come at last, and see he has cut off my hand with one blow of his sword!’ The giantess, overcome with fear, fled with her brother, and as they fled, they called aloud, ‘Fly, brethren, fly, take the path that is nearest, the fire burns high that will scorch up our dearest!’ All the giants turned and fled but even as they turned, Raja Rasalu rode up on Bhanur and challenged them, ‘Come forth, for I am Rasalu, son of Raja Salbahan, and born enemy of the giants!’ He killed the giants but the giantess, their sister, escaped, and fled to a cave in the Gandgari Mountains. Rasalu had a statue made in his likeness clad in a shining armor with sword, spear, and shield. He placed it as a sentinel at the entrance of the cave, so that the giantess dare not come out and starve to death inside.

The cave at Gandgarh, 50 kilometers northwest of Islamabad, where Raja Rasalu imprisoned a man-eating giant

Another adventure took Rasalu to Hodinagari where he defeated Raja Hari Chand and started to reign in his place. He talked to insects, dogs, cats, bucks, birds, deer and the dead. He garnered adulation and victories wherever he went. His voyages took him to places where he had encounters with equally intriguing characters such as a rival malicious King Raja Sarkap over a game of chaupur, a board game played with wooden pawns and seven cowry shells. He also had an encounter with Mirshikari, a renowned hunter from Deccan who could play the sweetest lute given to him by the Water-King, the immortal Khwajah Khizar. All the animals, when they heard the melodious music came and gathered around him. Mirshikari would than sneakily shoot them with his bow. Rasalu not only beat Sarkap in Chaupur, but stunned Mirshikari by his superior skills of playing lute. His travels took him to Bhoj, Delhi, and along the bank of River Ganges.

Rasalu became Raja after the death of his father, Raja Salbahan. Towards the end of the tale, attacks from the neighboring Ghakkar Raja of Jhelum ruined the city that Rasalu ruled and loved. It is said that after Rasalu’s death, there were no significant accounts of Sialkot for the next 300 years. Notwithstanding his ultimate decline, Rasalu’s heroic adventures and his bravery continue to be a subject of many popular Punjabi folk songs until today.

You may also like: