Written by: Sirat Gohar Daudpoto

Posted on: July 18, 2023 |  | 中文

| 中文

Buddhist archaeological site in Gumbat (or Gumbat-Balo Kale), Swat (Picture taken by Marco Pinelli of the Italian Archaeological Mission in Swat, Pakistan)

By keeping the cultural material away from the place of its origin, the so-called world-class heritage institutions are doing injustice to the heritage as well as to the place or the people it belongs to. If we wish to see or do some research on it, we would have to pay a huge amount of money, energy and time, although it belongs to us. What a pity! We demand the repatriation of all the cultural material that was taken out of our country in the past. We want to see and celebrate it and preserve it for future generations.

I wish to discuss the repatriation of Swat Treasures that was illegally transported to England by Evert Hugh Barger and his team, from the princely state of Swat in 1938. By Swat Treasures, I mean Gandharan objects which were discovered at different sites by Barger and his team between July and September 1938. According to a Dawn press release published on June 8, 2023, while addressing a seminar with the title of, “The Archaeology of Swat between the two World Wars: Institutional and Legal Issues”, at the Postgraduate Jahanzeb College Swat, Dr. Rafiullah said that “the Barger expedition to Swat had no institutional and legal cover as both the Archaeological Survey of India and antiquities laws were ignored. That’s why he took a huge collection of antiquities to England.” The participants of the seminar were vociferous in demanding the repatriation of Swat Treasures.

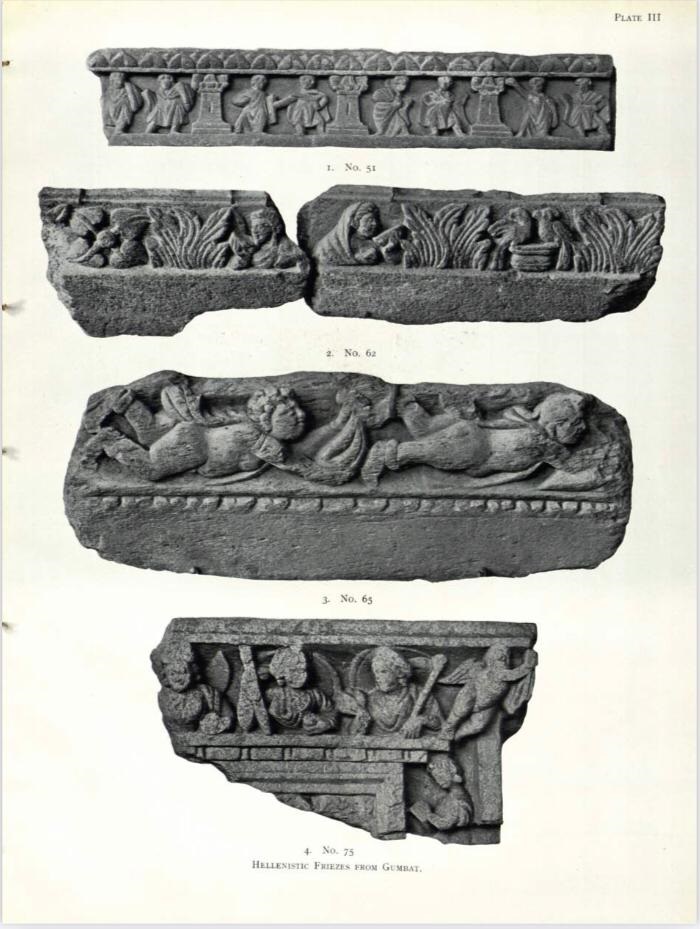

Gandharan Sculptures from Gumbat-Balo Kale (Scanned from the expedition report of Barger and Wright)

Swat was not part of the original plan of Barger’s expedition, for their goal was Chinese Turkestan, but the expedition was not permitted to go there because of political disarray in the area. Disappointed, Barger then diverted his attention to Afghanistan and approached the Afghan government with the help of a British Minister, in order to get permission for archaeological work in the Oxus territories. Again, luck did not favor him, the situation was not favorable for the British to work in the Afghan territories. In the meantime, Barger wrote to the British Indian government asking for permission to conduct archaeological work in North West Frontier Province and the tribal areas (present-day Khyber Pakhtunkhwa). He received a positive response from the Indian government. Initially, he was interested in Chitral, but later on, due to the unfavorable conditions in that area, he switched to Swat. Finally, Barger managed to get permission for the excavation of sites in Swat from the Indian government and the princely state of Swat. Meanwhile, he was also permitted to visit Afghanistan, where he headed from Swat along with Emanuel, leaving other two members of the expedition, Wright and Weatherhead, in Swat to continue archaeological exploration.

Swat could not escape the trowels of Barger and Wright. Encouraged by several societies in England and a number of scholars around the world, Barger led the archaeological expedition to British India (nowadays Pakistan), in search of the Gandharan pieces. His team consisted of four members: Barger, a lecturer of medieval history at the University of Bristol, was the leader of the expedition; Philip Wright, who was an assistant keeper of the Indian Section of the Victoria and Albert Museum; T.D. Weatherhead, who was the photographer and surveyor, and W.V. Emanuel, who was the interpreter of the team and in-charge of equipment, transport and so on. They excavated eleven archaeological sites located in the Barikot and Charbagh areas of Swat to procure Gandharan objects. The sites that were hunted for artifacts include Kanjar Kote, Gumbat, Amluk, Chinabara, Shaban, Tokargumbat, Abarchinar, Nawagai, Gumbatuna and Parrai in Barikot, and Jampure Dherai in Charbagh. At these sites, they found hundreds of objects of different types such as architectural fragments, Buddhist sculptures, pottery, metal objects and many more. All of the antiquities, except for the four artifacts that are likely to be found in the Peshawar and Swat museums, were transferred out of India, transgressing the archaeological legislation of British India.

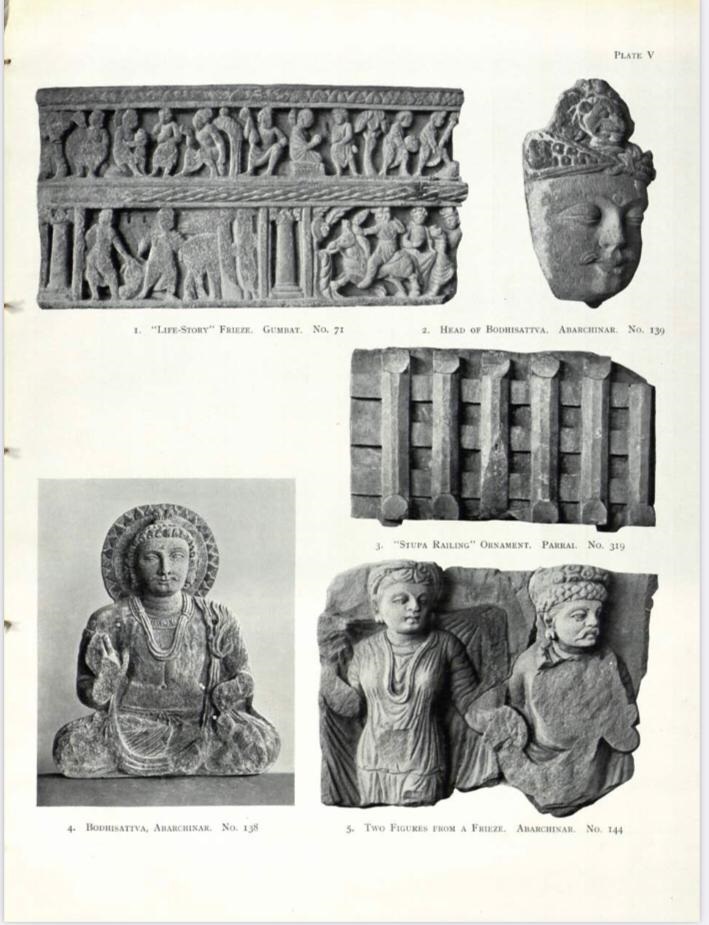

Gandharan Sculptures from Gumbat-Balo Kale, Abarchinar and Parrai (Scanned from the expedition report of Barger and Wright)

Although the expedition was supported by many societies in England, its main benefactors were the Victoria and Albert Museum and the Indian Research Committee. It has very recently been brought out by Dr. Rafiullah, in his article titled “The grey zones of antiquarian pursuit: The 1938 Barger expedition to the princely state of Swat”, which was published in the Modern Asian Studies in February 2023. The expedition was solely aimed at collecting the Gandharan antiquities for its sponsors, in particular the Victoria and Albert Museum, which was striving for obtaining Gandharan sculptures. Nearly two decades before Barger’s campaign, Stanley Clarke, the curator of the Victoria and Albert Museum’s Indian Section, concerned about the Museum’s inadequate collection, requested Sir John Marshall, the then Director General of the Archaeological Survey of India, for the sculptures of all the periods of Indian (and Pakistani) history. In his article, Dr. Rafiullah writes that “Marshall vehemently disapproved of the request. Around two decades later, the Victoria and Albert Museum acquired a handsome collection of Gandhara sculpture which Barger justified, in line with [Hercules] Read’s Eurocentric interpretation, with the epistemological trope of knowledge creation and the promotion of Indian studies in England.”

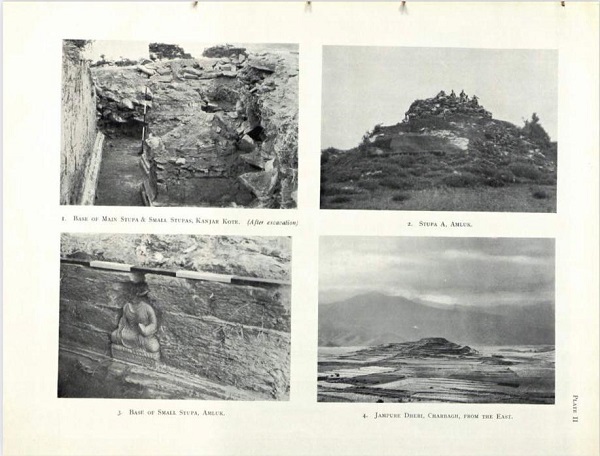

Old photographs of the remains of Kanjar Kote, Amulk and Jampure Dherai (Scanned from the expedition report of Barger and Wright)

Lastly, it is to be noted here that during that time British India had a well-set institution and strong legislation for archaeology, whereas, at the same time, the princely state of Swat was devoid of such protective legislation. Addressing the seminar in Swat, Dr. Rafiullah informed the audience that “During John Marshall’s Director-Generalship of the Archaeological Survey of India (1902-1928), archaeological activities on the outer periphery of British India were carried out after proper permission and were carefully watched. However, after Marshall’s retirement, laws were not followed, especially in some of the princely states, including Swat.” He has highlighted that the expedition did not have a work permit and flouted the legislation in place in British India.

Overall, it can be said that Barger was a treasure hunter and his expedition to Swat was merely to collect Gandharan pieces for the sponsors of the expedition. We now know that Barger violated the rules by transporting the Swat Treasures out of the region and India (including nowadays Pakistan). Now, the government of Pakistan should demand back the Swat Treasures for its people.

You may also like: