Written by: Haroon Shuaib

Posted on: August 23, 2024 |  | 中文

| 中文

From a very early period, calligraphy was considered as the supreme visual art form in China

Calligraphy is considered supreme among the visual arts in China. From a very early period, calligraphy was considered not just a form of decorative art; rather, it was viewed as the supreme visual art form and was more valued than painting and sculpture. In fact, from ancient times in China, Calligraphy was ranked alongside poetry as a means of self-expression and cultivation. The art of calligraphy, the stylized artistic writing of Chinese characters, unites the many languages spoken in China. The fact that the early Chinese written words were simplified pictorial images, indicating meaning through suggestion or imagination, lends itself to simple images, capable of developing with changing conditions by means of slight variations.

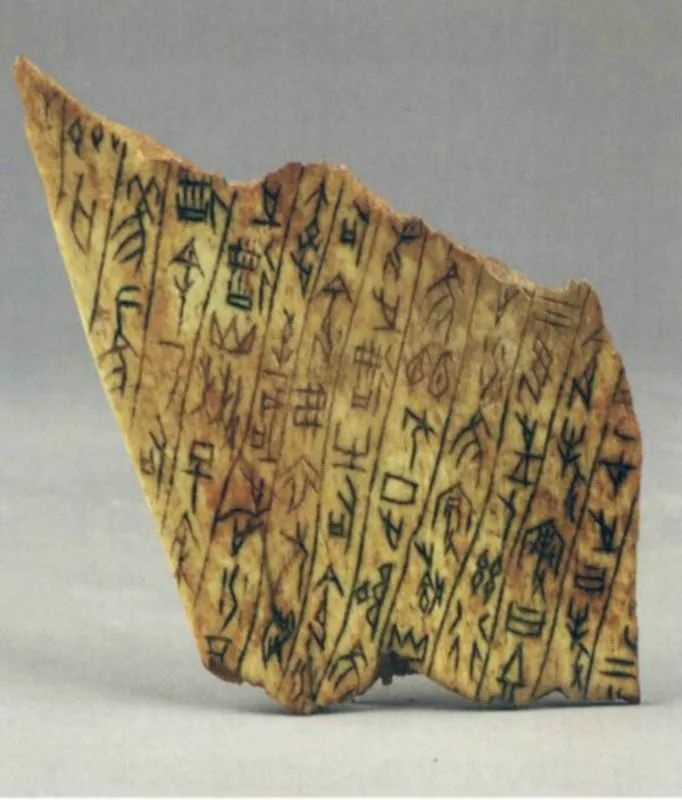

According to the Encyclopedia Britannica, the earliest known Chinese logographs are engraved on the shoulder bones of large animals and on tortoise shells. For this reason, the script found on these objects is commonly called jiaguwen, or shell-and-bone script. Archaeologists and paleographers have demonstrated that this script was widely used in the Shang dynasty (c. 1600–1046 BCE). Each of the ideographs was carefully composed before it was engraved. Although the figures are not entirely uniform in size, they do not vary greatly. Since the literal content of most jiaguwen is related to ancient religious, mythical prognostication or to rituals, jiaguwen is also known as oracle bone script.

Oracle bone inscriptions, or Jiaguwen, are widely regarded as the oldest-known, fully-developed form of Chinese writing

It was said that Cangjie, the legendary inventor of Chinese writing, got his ideas from observing animals’ footprints and birds’ claw marks on the sand as well as other natural phenomena. He then started to work out simple images from what he conceived representation of different objects. Each image is composed of a minimum number of lines and yet easily recognizable. Nouns must have come first. Later, new ideographs had to be invented to record actions, feelings, and new variations were added to the already existing ideograph to give a new meaning to each alteration.

Jiaguwen was followed by a form of writing found on bronze vessels associated with ancestor worship and thus known as jinwen (metal script). Wine and raw or cooked food were placed in specially designed cast bronze vessels and offered to the ancestors in special ceremonies. The inscriptions, which might range from a few words to several hundred, were created by different artists. The bronze script—which is also called guwen (ancient script)— represents the second stage of development in Chinese calligraphy. In the 3rd century BCE, the bronze script was unified and regularity enforced. Shihuangdi, the first emperor of Qin, gave the task of working out the new script to his Prime Minister, Li Si, and permitted only the new style to be used. This third stage in the development of Chinese calligraphy was known as xiaozhuan (small seal) style. Small-seal script is characterized by lines of even thickness and many curves and circles. Each word tends to fill up an imaginary square, and a passage written in small-seal style has the appearance of a series of equal squares neatly arranged in columns and rows, each of them balanced and well-spaced.

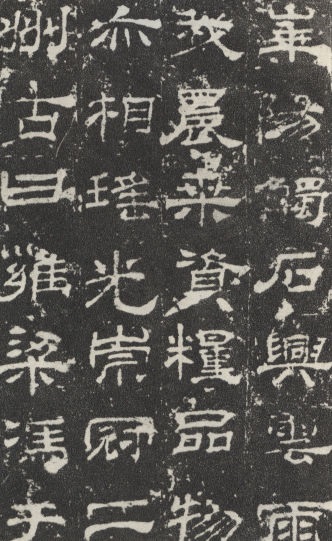

The Seal Script became the standard script for official documents and inscriptions during the Qin Dynasty, as it symbolized the authority and power of the emperor.

This uniform script had been established chiefly to meet the growing demands for record keeping. Unfortunately, the small-seal style could not be written speedily and therefore was not entirely suitable, giving rise to the fourth stage, lishu, or official style. Lishu style did not have circles and there are very few curved lines. Because of the speed needed for writing, the brush in the hand tends to move up and down, and an even thickness of line cannot be easily achieved. Lishu is thought to have been invented by Cheng Miao (240–207 BCE), who had offended Shihuangdi and was serving a 10-year sentence in prison. He spent his time in prison working out this new style, which opened up seemingly endless possibilities for later calligraphers. Freed by lishu, they evolved new variations in the shape of strokes and in character structure.

As lishu curtailed the freedom of hand to express individual artistic taste, a fifth stage developed—zhenshu (kaishu), or regular script. No individual is credited with inventing this style, which was probably created during the period of the Three Kingdoms and Xi Jin (220–317). The Chinese write in regular script today; in fact, what is known as modern Chinese writing is almost 2,000 years old, and the written words of China have not changed since the first century of the Common Era. “Regular script” means “the proper script type of Chinese writing” used by all Chinese for government documents, printed books, and public and private dealings. In this style, each stroke, each square or angle, and even each dot can be shaped according to the will and taste of the calligrapher. Indeed, a word written in regular style presents an almost infinite variety of problems of structure and composition, and, when executed, the beauty of its abstract design can draw the mind away from the literal meaning of the word itself.

Chinese calligraphy is a meticulous art requiring specific tools. The "Four Treasures of the Study" – brush, ink stick, inkstone, and paper (or silk) – are essential. The brush, typically made of animal hair, is wielded with precision to create varied strokes. Ink, traditionally made from soot and glue, is ground on the inkstone to achieve the desired tone. Mastery of these tools, combined with years of practice, is crucial for producing calligraphy that is visually harmonious and spiritually resonant. China's paper revolutionized communication. Traditionally credited to Cai Lun around 105 CE, papermaking actually predates this by at least a century. Crafted from materials like mulberry, hemp, and bamboo, paper replaced costly silk and heavy bamboo scripts. Combined with inkstone, brush, and ink, it formed the revered "Four Treasures of the Study," essential tools for scholars and artists.

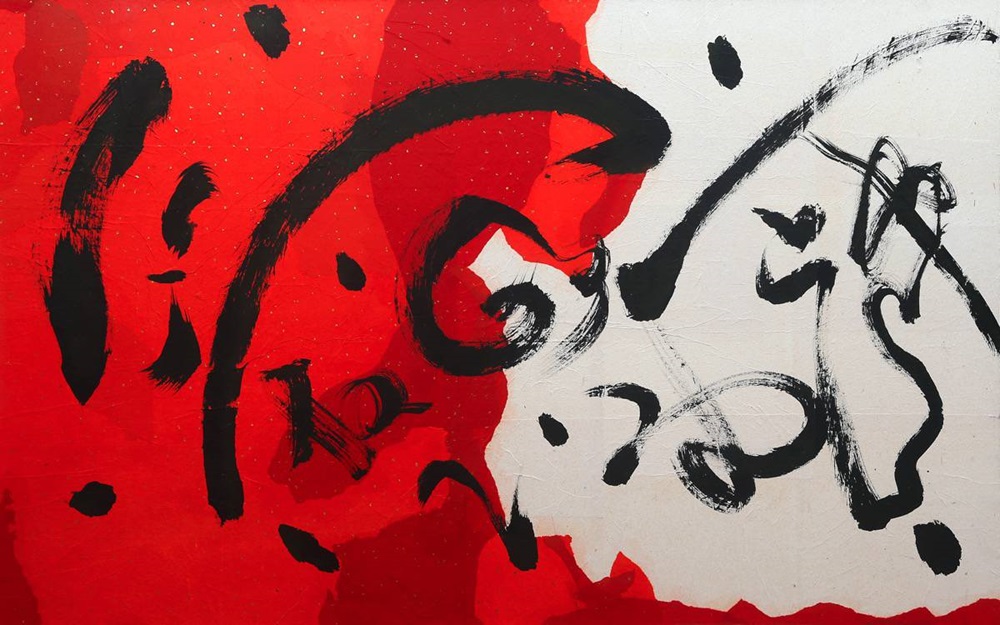

Contemporary artists continue totake inspiration from Chinese calligraphy to create art - The-Rhythm-of-Love-2 by an Indonesian Artist

The fundamental inspiration of Chinese calligraphy, as of all arts in China, is nature. In regular script each stroke, even each dot, suggests the form of a natural object. As every twig of a living tree is alive, so every tiny stroke of a piece of fine calligraphy has the energy of a living thing. Printing does not admit the slightest variation in the shapes and structures, but strict regularity is not tolerated by Chinese calligraphers, especially those who are masters of the caoshu. A finished piece of fine calligraphy is not a symmetrical arrangement of conventional shapes but, rather, something like the coordinated movements of a skillfully composed dance—impulse, momentum, momentary poise, and the interplay of active forces combining to form a balanced whole. No wonder that in 2009, UNESCO put it on the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity.

You may also like: