Written by: Aiza Azam

Posted on: October 28, 2013 |  | 中文

| 中文

Mustansar Hussain Tarar granted a recent interview to Youlin in which we talk about his multi-layered life and his unique expression of creativity.

You are an actor, a compere, a novelist, a columnist, a poet and a travelogue writer. Which of these pursuits has given you the most satisfaction, the biggest return? And which of them has come most naturally to you?

I don’t think any of these pursuits are essentially very different from each other. They all stem from the same centrifugal force of creativity and are just different media of expression; I use them alternatively, depending on my mood and on the need of the hour. Television, I find limiting to creativity, because it is bound by the requirements of time. Being a columnist gives you more room because while you write on current issues, You’re not really confined to any one topic; in my columns I talk about literature, films, archaeology, a whole diverse range of themes. As for the travelogue, it is a unique style of writing. The narrative I construct to recreate a journey tends to belie the actual duration of it. It is about translating the experience in its entirety. I once wrote about the time I spent in Ghaar-e-Hira. I stayed there for one night only, but creatively I was in that cave for six months. But I believe it’s the novel that is my favorite genre. You take the inspiration from a character or two and then weave your own experience into it. It’s different from these other forms of literary expression because you need to have a vast experience of human history and culture, and by experience I do not only mean that you have to have gone through something personally but to have felt or witnessed something; and then sometimes you do not have firsthand experience, but you must be able to deduce what goes on in your protagonist’s mind, from the saint to the street prostitute. For all these different human behaviors, you have to be aware of their psychological makeup.

That being said, though, I cannot say that either of those hats – the poet, the novelist, the travelogue writer, etc. – most translates who I am. If I had to commit to a single identity, I would say I’m a vagabond.

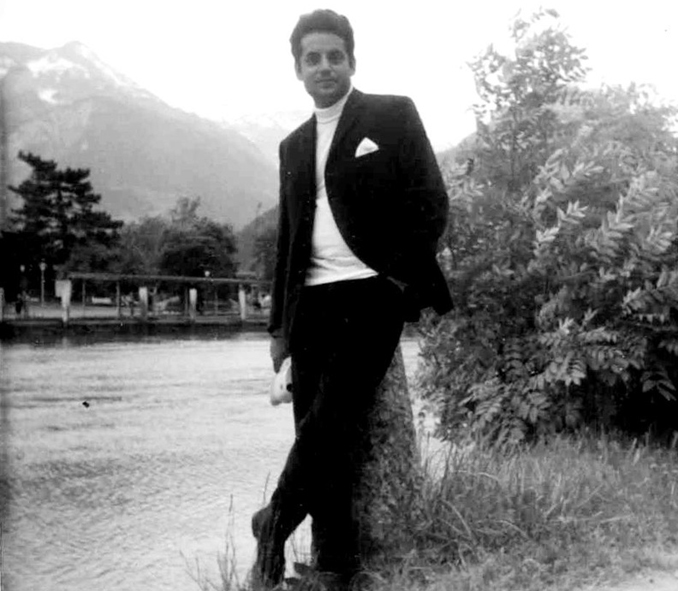

|

| At Lake Thun in Switzerland, circa 1975 |

Where does the inspiration for your novels come from? How long do you usually take to write one, and what does it take (in terms of atmosphere, time, etc)?

Inspiration comes from various things. I’ve written six or seven novels in the last 22 years, and each one has been inspired by something different. For instance in the trilogy I wrote on rivers drying up, which begins with Bahao (The Flow), I was inspired by the drying of our rivers, and the idea that when a river dies, a whole civilization dies with it. For Raakh (Ashes), I chose the river Ravi. And Qurbat-e-Marg Mein Mohabbat (Love, When Death Knocks at the Door), which completes the trilogy, was basically just my fancy, in which I imagined that the rivers are drying up. The basic question for me was that there must be someone in every culture or city, in every village by the side of a dying river, there must be one person who suddenly realizes one fine day that the river is drying up; now that is a great burden to carry because he knows what will happen with it; the whole culture and the entire population will go too, taking down with it the flow of all inspiration, food and love. I imagine that person would feel the terrible burden of being the only one to realize all this but cannot share his fear with anyone lest people think he is going mad. It sounds almost like a ridiculous proposition really, but a writer, given a certain atmosphere, will always experience things differently from another person. As long as you have that creative energy in you, that fire, you can write anything, anywhere; if not, you could have all the stimuli in the world and not be able to create a thing from it.

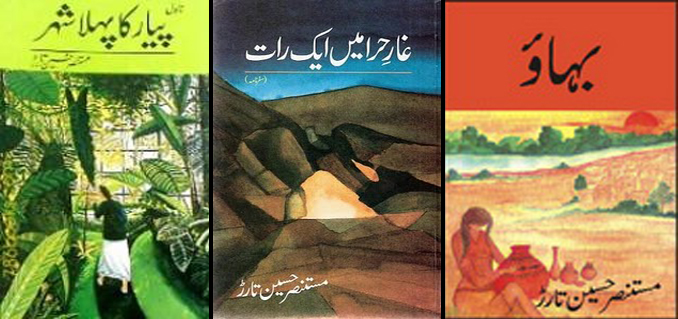

|

| Pyar Ka Pehala Shehr (The First City of Love) Ghaar-e-Hira Me Ek Raat (A Night in the Cave of Hira) Bahao (The Flow) |

What kind of literature do you like to read? What are you reading at the moment?

My reading varies from time to time. I read everything, from history and theology to fiction, the latter being my main interest. I usually read three or four works in parallel, and they constitute a mixture of heavy reading and lighter material for relief. Over the last several months I’ve read a lot of Mo Yan. He is sheer genius; his novel Red Sorghum was truly impressive, and I feel ordinary when I read the work of a master such as him. I’ve read all his works, and even the speech he gave at the Nobel ceremony in Oslo. In general, I read a lot of different authors and if I find one I like then I read all their works. For instance, I’ve read a lot of Orhan Pamuk and Yasar Kemal. I’m also fond of Tolstoy, Dostoyevsky and Pushkin, so, all the classics.

|

| With Samina Ahmad in a scene from a play by Patras Bukhari |

You attended the Karachi and Islamabad Literature Festivals this year. What are your thoughts on young Pakistani novelists? Do you feel there is a marked difference between their writing styles and the themes they explore, and that of writers from other generations?

You have two different categories of young novelists here: Urdu writers, and English writers from the subcontinent who settle abroad and write about their indigenous culture. The latter come out with a very fresh approach in that it’s dominated by Western thought and culture and it’s new. But I feel that, with the exception of the novel A Case of Exploding Mangoes by Mohammad Hanif or maybe Mohsin Hamid’s The Reluctant Fundamentalist, these works are unable to capture the essence of the people and place they are writing about. It’s a distinct species of writers; they write with a passion but they aren’t absorbed by what they are writing about.

I also feel that most of our younger generation is not aware at all of what has been created in Urdu. That being said, I don’t condemn this new, internationally known breed; but I will say that they form part of neither Western nor indigenous literature.

Subho Bakhair Pakistan (Good Morning Pakistan) was a staple part of the mornings of a generation of children. How do you feel about the type and quality of morning programs today?

With Subho Bakhair, I was very clear that I wanted the ordinary Pakistani to identify with it. I’d seen Good Morning America and Good Morning Vietnam, and I had that in mind. I wanted it to be about the essence of Pakistan, and part of that is why I would wear a shalwar kameez and why children on the show came to know me as Chaacha Ji (Dear Uncle). It was all very wholesome. And it wasn’t just for children; part of it was, but the rest of the show catered for their parents too. Present day shows are not morning shows; I’d call them variety musical shows. But they are obviously popular, which means they cater to the needs of the populace; and isn’t that sad. The thing with television today is that unlike before, you can’t experiment much. Programs today are a slave to the ratings. I don’t blame the people who create these shows, really. If I were given a morning show today for which I were to decide the content and program, I don’t think people would be interested; people, the large majority of them watching these morning shows in their homes, want quick entertainment. And I don’t believe in pure entertainment; I think if you’re creating something, whether it’s a work of writing or a TV program, it should affect the populace and make them think.

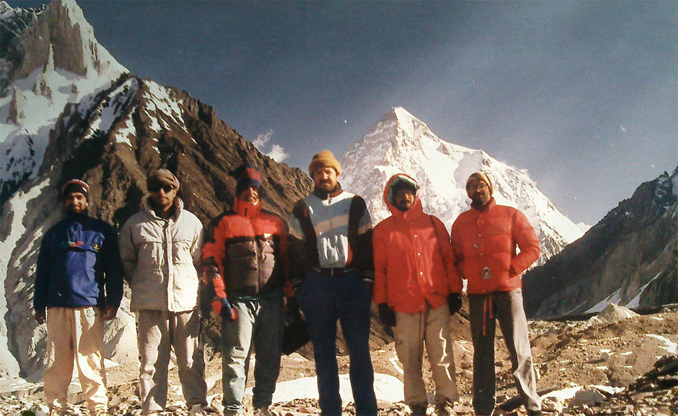

|

| On the K2 Concordia trek, August 1993 |

Where does your love of travelling stem from? Why write travelogues about your trips? Is it to inform other people, or is it primarily to record memories?

I’m not a technical travelogue writer. I’m not a recorder of events or a journalist either who reports exactly what he sees. I am, at the very least, a creative person. So whatever I see or wherever I go, I have my own perspective. Maybe others see it with a different one. Some say I mingle fact with fiction. And they are right, because when you say fiction, you don’t mean the untruth; you simply refer to what has been produced as a result of creativity. So I’m not a great explorer or anything, nor a researcher of geography. Basically, I’m an emotional and creative man and whatever affects my whole body and soul, I can narrate it. It may be that I catch a glimpse of a mountain for two seconds, and then I narrate that moment in ten pages. I write because I want to touch people’s hearts; and I think I do, if anything is to be taken from the fact that I’ve been a best-selling fiction author for 23 straight years. At a function in Karachi that Mohammad Hanif had organized, he said that he had met people in Pakistan who had only read either Mustansar Hussain Tarar or the Holy Quran. I understood that because the people who read my work generally have no inclination towards literature. The objective is to reach out to people who may be completely ignorant of the existence of this genre of writing and draw them to it.

Which place that you have visited during your travels has had the most impact on you? Has there ever been a visit that turned out to be disappointing, not being what you expected it would be?

I’ve written twelve travelogues about Pakistan’s Northern Areas. Fairy Meadows is the most beautiful place I’ve been in those trips up north. As far as other countries are concerned, you start to cherish them from the people who meet you there, with the sort of treatment you’re given. No matter how fantastic Switzerland is, it doesn’t necessarily constitute a beautiful experience because the people there are very cold. Conversely, I find the general landscape of Afghanistan majestic, the barrenness of its desert awesome. I cannot pronounce a single country as being my favorite, with the exception of my own. As a rule, wherever I go, I go with a blank mind. And because of this I’ve never been disappointed by any country. It could be beautiful in ways which are not my ways. You see the variety of human beings, their thoughts and their religions, and it’s all a different experience. You know, I haven’t really travelled all that much; as my wife generally says, I talk more about it than I’ve travelled. I haven’t been to Southeast Asia or Africa or South America. When I’m asked what I’ve learnt from my travels, naturally the answer is that I’ve learnt a lot. I feel my whole personality is made from the different cultures of the place I’ve visited all over the world. Like I went to England at 16 or 17 and absorbed a lot of European traits. At the time I wrote my first travelogue, Niklay Teri Talaash Mein (Setting Out in Search of You), I was sort of Westernised, in that my approach was whatever all you experience must be written down or narrated. But now I know that while that may be the correct approach within certain literary cultures, in others it isn’t.

How do you prefer to travel?

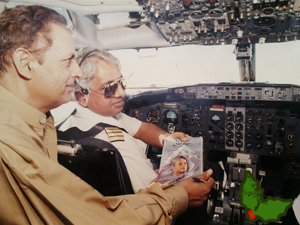

|

| Presenting the pilot a copy of K2 Kahani (The K2 Story) onboard the K2 Air Safari |

Well, my preferences have changed over time. When I was younger I travelled alone. And I never travelled by air; I thought it was sacrilegious to travel by air! Most probably, I was the first Pakistani hitchhiker in Europe at the time I first began. Then followed a period when I travelled across our Northern Areas. Initially, I went alone, but when I wrote Hunza Dastaan (Destination Hunza), my six year old went with me. And then after that I’d be accompanied by my whole family. Now my son and daughter live in America, and when my wife and I go to visit them, it’s a different kind of travelling. It’s all very organized and orchestrated. My travel experiences have changed too. It used to be that I’d travel across Europe, like I remember I did once in France, without meeting a single Pakistani throughout, and that actually gave me the power to understand that country. But now, I go by invitation and it seems all we do abroad is meet Pakistani people and stay in Pakistani homes. The world I remember travelling once is simply not there anymore. Way back then, I was visiting Hamburg and I remember that a young local boy looked at me and, going up to his mother, innocently asked, “Mom, is that man made of chocolate?” But you won’t find anything like that now because we’re all everywhere.

|

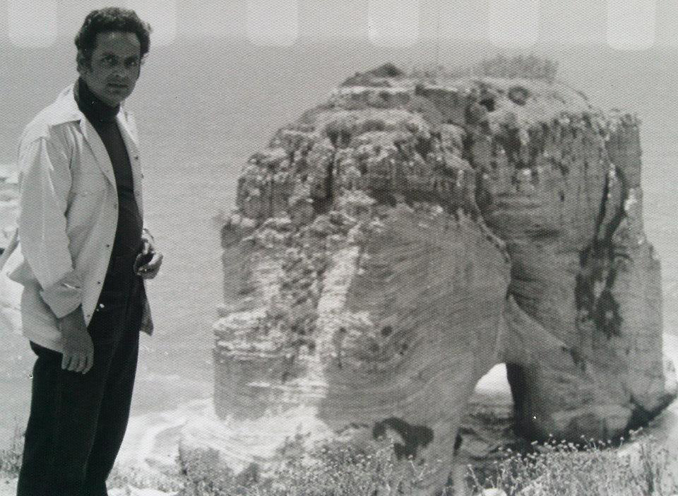

| In front of the famous Rock of Pigeons in Beirut, circa 1975 |

What places do you still plan on visiting?

I’m, Mashallah, 74 now, and I don’t have that desire anymore to travel; the exuberance is not there. Maybe with the exception of going up into the mountains to camp there and just staying there. So I don’t have that typical desire anymore.

Mustansar Hussain is currently revising the final draft of his next book, a travelogue on Xinjiang from his most recent visit, titled Lahore Se Yarqand (From Lahore to Yarqand). He has also written a series of articles and columns in Urdu based on his visit, which have been published in Akhbaar-e-Jahaan, Nai Baat and Aaj. The book is a project undertaken in conjunction with the Pakistan-China Institute and the Information Office of the government of Xinjiang.

All images have been taken from Mustansar Hussain's website.

You may also like: