Written by: Eeman Amjad - Posted on: June 24, 2013 |  Comments | 中国 (Chinese)

Comments | 中国 (Chinese)

Google Translation: اُردو | 中文

Zaland Khan Mohommadzai was only six when he began playing the keys of the harmonium. As a small boy he grew up in Peshawar, drifting through the city’s myriad cultural - a city that is known for its Pukthun and Dari music. His own father encouraged prominent musicians such as Daud Hanif, and Zeb and Haniya. Zaland believes that the music was a gift of being part of this world.

This world, that introduced him to an instrument called the rabab, the sweetheart of Pushto music.The rabab is made out of a single piece of wood from a mulberry tree, and animal skin, which is mostly goat skin. It was around two years ago that Zaland met his rabab. He was putting away a package for his father’s friend when he heard a musical voice from within, strings of the rabab. The beauty and melody of the instrument enchanted him. His father, noting his son’s infatuation, encouraged him to learn how to play. There was no teacher; nevertheless every evening they would sit together, the father listening keenly as his son practiced the soft and slow harmony of the rabab. After four months, Zaland could skillfully play the drones, melody and sympathetic strings of the instrument that would eventually come to define him.

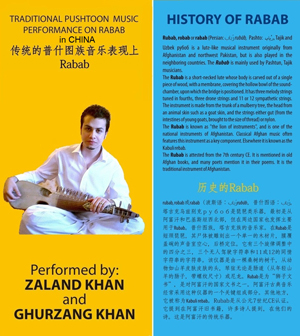

He was in his last year of school when he was asked to play in Peshawar’s IMS University, but the biggest moment for both Zaland and his rabab came when he was asked to play at a cultural exhibition in China. The Pakistan Carpet Manufacture Association sponsored him, after Akthar Niaz heard about him through his son; once again, his father encouraged him to take this journey.

|

| Zaland and his Rabab |

The experience would prove to be a life changing one. Describing the atmosphere at the exhibition, Zaland related that there were flags from all over the world, and each country was represented by a sacred piece of its culture. For Zaland, that sacred piece was the wooden treasure he carried, that was a symbol of his history and culture. The Governor of Chinghai Province, as well as the Pakistani Ambassador to China, Masood Khan, were in attendance.

|

| Poster from Chinese cultural fair |

Zaland reminisces about the reactions of his Chinese audience. People of all ages, laughed, danced and cheered together to the beat of the rabab, happy and carefree, their spirits becoming more animated the more he played. They would come and touch his rabab, and though he couldn’t understand the language when they talked, he could easily glean their appreciation of the music, communicated through the cheers and lively chatter of the crowd. He would love to go back one day, to play with their musicians and to learn their music. Chinese tunes and melodies, he reflected, are a lot like Pakistani ones.

Zaland also expresses an interest in going to more cultural trade events because, he believes, “Cultural trade events are a peaceful means of communication and you exchange musical concepts and other ideas. At the cultural trade event in China, a lot of countries were present and behind the stage we would all jam. It was all the same we were all having the same experience.” He believes that the diversity in musical instruments has the ability to harmonize itself into a single tune, and that is the beauty of sharing music. He especially expresses an interest in travelling around Central Asia. “Afghani and Pushto is the same, but I mean Uzbek, Tajik and India. Just the beats and the music are different, even though the instruments are so similar.”

His experience in China taught him that music was a key instrument in transcending past all vernacular and cultural barriers. “When I perform in Peshawar everyone gets it. They are familiar with Pushto music, but in Islamabad or outside the country you would think it would be more difficult. But music, it has a universal way of communicating with other cultures, and whether you speak Punjabi, Urdu, or Chinese, it doesn’t matter. The music is new and different. It becomes a new way of communicating.”

It was not just the gift of the music that came to Zaland from his city, but the inspiration behind the music as well. The poetic words of Ghani Khan and Rehman Baba inspire him to transcend the superficialities of society to truly comprehend his world. The meanings of the words aren’t random, he explains. They signify something deep. They tell a story of darkness, love, beauty, and also of a social consciousness. The poetry can describe the features of the beloved, but at the same time depict the darkness in society stemming from a social gap between the rich and the poor. Recently, Zaland has recorded a song 'LaaL' the beat and music are composed by him and the poetry is by (late) Rehman Baba. The song is about highlighting and understanding the contradictions in life.

The superficiality and glamour, Zaland observes, are what most young musicians in Peshawar are obsessed with. They want to change the standard of music, modify it to a rock and roll beat. Change is good, he thinks, but he emphasizes the importance of sticking to cultural music. Changing the whole theme and structure is like changing your roots. “I would like people to know more about traditional music. I tell them about the rabab and other cultural instruments. Even though they don’t want to know. You hardly see traditional music in the media, so youngsters are unaware of typical instruments. They talk about strings like acoustic and electric guitar. Guitar is very common and that is all they play. People like my music because it is different, and at the same time reminds them of who they are, their history and culture.”

|

Zaland loves music, but it is something he pursues as a hobby. He plans to continue his education and is beginning his Bachelors. Recently he has been recording with a producer in Peshawar, Ali Haider. He would love to one day play with Ferhad Darya, the Michael Jackson of Afghanistan. He is proud of having played with Ustad Amjad, a noted tabla player in Pakistan. He considers music more of a part time job, a passion, for which he is grateful for his family especially his father who encouraged and got him different musical instruments.

Being able to play for people, making them appreciate the music as well helping them remember who they are is what motivates him. The soft lyrical tune of the rabab, integrated slowly into the beat of the djembe, and defined by the golden words of Rehman Baba:

When I am looking on my love, hot tears will run,

upon my face like melting wax beneath the glowing sun

This is what motivates the young twenty-one years old rabab wala. He is carrying with him not only his beloved rabab, but also his literature, culture and history, something he wants to share with the rest of the world.